WARNING: Spoilers for Westworld Season 2.

Westworld Season 2 failed because it couldn't get over the mystery-cracking fans on Reddit. A show going bad is nothing shocking - most series run out of steam after a few years on the air, with only a handful of true greats making it to a finale without a dip - but this is a rather startling case; Westworld not only had the drop occur in its second season, but the downfall comes from the very facets that made it so exciting in the first place.

Season 1 was a massive hit for HBO, netting ratings that almost matched Game of Thrones' debut year and placing highly in a host of "Best of 2016" lists, and so expectations were high for Season 2. However, it only took a couple of episodes for something to feel off. Westworld still looked great, but its story lacked the finesse and, as it moved on, required confidence to buy into such a complex magic trick. Episode 8, "Kiksuya" - almost a home run - aside, the show never suggested anything truly inspired.

Related: What To Expect From Westworld Season 3

Now it's finally over and while the Season 2 finale did at least answer many big questions - to be clear, Westworld still make sense - it did nothing to justify the journey. How did this happen? How did Westworld go from the apex of HBO's lineup to just another convoluted sci-fi series? And what lessons do showrunners Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy learn for the impending Season 3?

- This Page: Westworld Season 2 & The "Plan"

- Page 2: The Two Big Mistakes Westworld Season 2 Made

- Page 3: How Jonathan Nolan's Hatred Of Reddit Broke Westworld

Westworld Season 2 & HBO's "Plan"

One thing that multi-season epic TV shows really like to push is that they have a plan. Narrative cul-de-sacs and years of buildup are excusable if there's a destination and thus greater purpose to everything that's being told, right? The logic is somewhat flawed given how classics like Breaking Bad were famously constructed on the fly (Vince Gilligan introduced the machine gun in the Season 5 premiere with no clue to its payoff), but something has to be said about knowing where your heading.

The problem comes when showrunners exaggerate the nature of that plan. When Lost's Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse managed to wrangle a firm end date during Season 3, it looked like they were going to be enacting a longterm gameplan, and yet all they would say was set in stone was the show's "final image". That ended up being Jack's eye closing, a mirror of the first image and recurring motif throughout the show, so hardly indicative of narrative (which we now know was defined more season-by-season). The same is true of How I Met Your Mother: Carter Bays, Craig Thomas shot the postscript with Ted's children imploring him to ask Robin out following the mother's death way back in 2006 after Season 2 (due to the risk of them ageing out), but that didn't mean any grander scope for the actual meeting existed (and it also locked the ending in place even as the show moved away from the ideals it spoke of). Plainly, there's a difference between and plan and an vague end goal.

Westworld appears to fall into this set. It was, from very early on, sold as having a multi-season plan, with as many as five in discussion. From the standpoint of the tightly-wound Season 1, that led many fans to believe we were dealing with a grand story; one that justified using up the base premise in the first ten episodes. However, Westworld Season 2 would seem to refute that: nearly all of its narrative points relating to The Door, human-host hybrids and Delos' true goals all come exclusively from this run, with none of it ingrained in the previous season (while certain things, like what's in Abernathy's brain, is changed). In terms of a longer plan, it reads as having a start - the host uprising - and an end - Dolores and Bernard moving into the real world - with everything else filling in the gaps.

Related: Jurassic Park and Westworld Were Rebooted The Wrong Way Round

Now, both Lost and How I Met Your Mother are well-remembered, so this fill-in-the-blanks style of TV show writing needn't be immediately flawed. However, the risk is that it skews focus away from the journey - the majority of an ongoing TV series - to the lynchpin shocker points; no journey, no fun. You can feel that in Westworld Season 2, with everything purporting to be to some greater purpose yet that cohesion lacking for most of the trek. This is the start point of Westworld Season 2's issues, but it goes deeper.

Page 2: The Two Big Mistakes Westworld Season 2 Made

Westworld Season 2 Has No Clear Characters

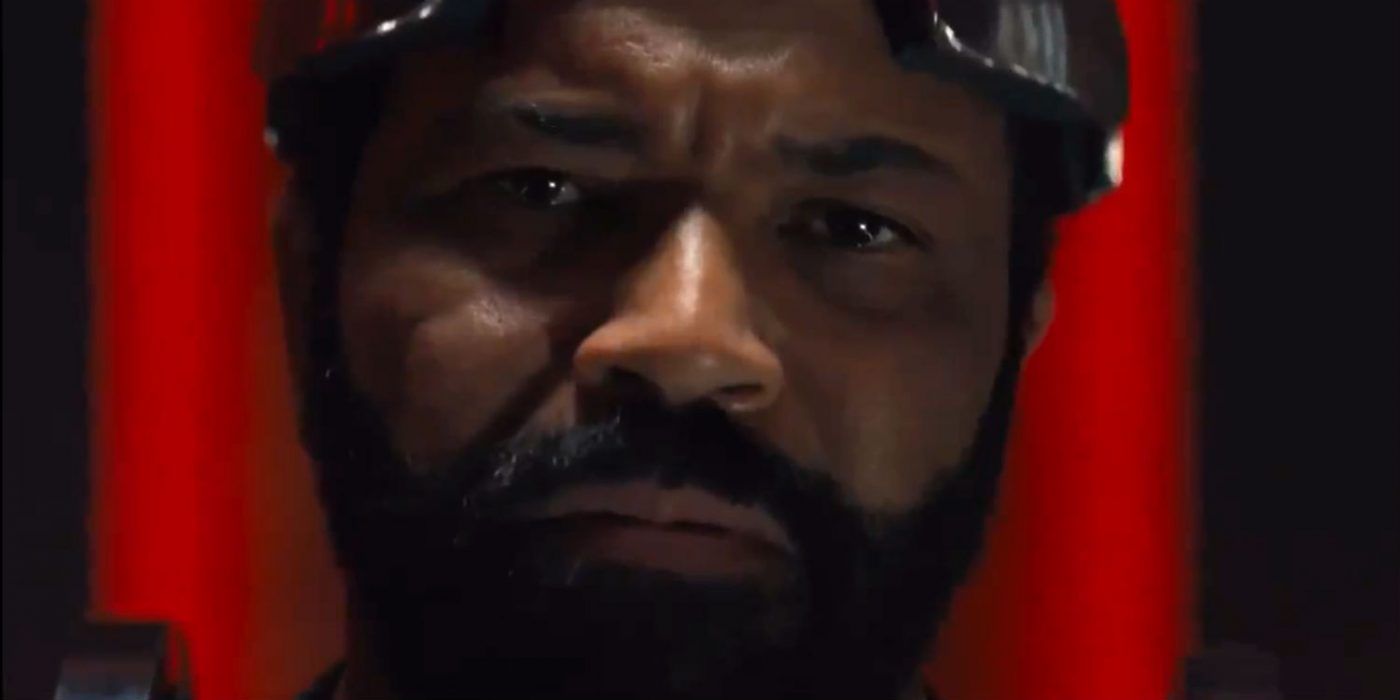

Westworld is a HBO headliner, so it naturally looks amazing and every actor gives their all no matter how small or weird their role. Season 2's problems instead lie almost exclusively with the story, both in how it's told and the characters that inhabit it.

What made Westworld so immediately exciting in the TV landscape was how by its very nature the way characters operated was different. The show opened on James Marsden seemingly entering the park as a guest, only for him to be shot and killed by the Man in Black, revealing him as a host, setting up the idea of loops, and planting the suggestion that everything may not be as it seems. In Season 1, the show had immense fun with amoral guests, cocksure staff and unenlightened hosts gradually having their worldview twisted as part of the bigger narrative. Mind wipes, doubles, personality redos: everything was above board. The danger, of course, was that having memories changed and programmed personalities would reduce any sense of organic development, yet Westworld found the drama within it.

What's so shocking, then, is that when Season 2 went to remove the hosts from their pre-ordained track and thus enabling an easier set of relationships, everything became confused. What was freedom? The Maze had framed it as a road to consciousness, but which of these hosts were truly aware of their existence, and who of those were capable of free will was nebulous for much of the season. That question - the nature of free will - was definitely something the show wanted audiences to ponder - Bernard even spells it out in an obtuse final monologue - but it was being asked in the wrong form: it was as a fault of the show's characterization, not a quirk of the story.

Related: Who's Still Alive After Westworld Season 2 (And Who Can Come Back)?

This is perhaps best seen in Dolores. In Season 1 an unsuspecting lynchpin who merged good and evil to create the closest artificial human, right from the off Season 2 seemed unsure of what to do with her. Was she free? Was she just on the Wyatt program? Or was something bigger and deeper going on? This question loomed large and then was removed from the show as her mission to the Valley Beyond shifted to the forefront, something that was also unclear. At no point in the first nine episodes was what she was wanting or thinking ever truly conveyed. The intention seems to have been to make her into something of a villain, which was definitely a bold and interesting move, but without any entrance point to this, she came across simply as removed.

Timelines Go From Twist To Narrative Crux

The real coup of Westworld Season 1 wasn't its free-wheeling characters, but its multiple timelines. The big twist of the first year (albeit one many figured out, a fact that we'll come back to) was that everything with Logan and William actually took place decades before the bulk of the show, compassionately telling us the origin of the violent Man in Black and providing the start of Dolores' awakening. It was a complex trick that relied on confusing seeding, but fitting of his previous experience on the likes of Memento and The Prestige, Jonathan Nolan pulled it off. The key, ultimately, was purpose: every trick had a reasoning and link to the wider story.

Season 2 adopted multiple timelines as a plot device again, with events taking place straight after the host uprising, two weeks later, and then at random points throughout the past of the park. It was mass expansion, with Season 1's two time periods making way for dozens all unfolding concurrently. The show did make efforts to try and connect them to the present events, with Bernard's malfunctioning and William's recollections serving at story justification and episodes (usually) making sure each period jump had some thematic grounding, but halfway through it was making rather simple arcs convoluted. Random shots would "foreshadow" a later reveal and in the finale the show was audacious enough to have a scene taking place far in future edited as if it was in the present with no hint of a mistruth until the end-credits scene.

There are exceptions where this approach worked - the development of James Delos' bid for immortality in Episode 4 and Akecheta's decade-long journey to self-realization in Episode 8 - but for the most part these timeline jumps were less about serving the story than they were obfuscating it. Laying it down in a linear timeline, Westworld Season 2 has a clear, flowing narrative that offers up some coherent ideas. But when it's so scattered and full of teases of payoff that would be just regular plot points if done chronologically (see: the many doors that weren't "The Door"), it begins to lose a proper coherence, and with it a sense of what it's trying to say.

Related: Westworld Timeline Explained: How It All Connects

When you have ill-defined characters wandering aimlessly through an over-twisted narrative, you're already removing a lot of emotion but are also going to struggle to do grander things with your story. The philosophical, religious, literary and other cultural references and metaphors that run through Westworld are plentiful, but when everything is so vague and distant none of it can mean anything. It all comes together to make it look like Westworld is trying to be too high-minded for its own good. And that's because it is.

Page 3: How Jonathan Nolan's Hatred Of Reddit Broke Westworld

Westworld's Showrunners Disliked Fan Theories Getting It Right

Westworld Season 1's best aspects have proven to be its downfall, and it may be the most discussed element of the show's debut that fully broke Season 2: fan theories.

For all the subterfuge and narrative pivots, fans managed to crack nearly all of Westworld Season 1's mysteries. Bernard is a host replica of Arnold? There were two timelines and William is a young Man in Black? Maeve is basically God? Everything was pieced together from some very early clues, meaning that the final stretch was for many less about being surprised than it was being validated. That didn't mean anybody enjoyed the season less - there was a sense of satisfaction in figuring it out rather than the stomach pit of being spoiled - but somebody evidently forgot to tell that to Jonathan Nolan.

Related: Westworld: What is the Significance of Valley Forge?

From when Season 1 first aired, it was clear that the Westworld co-creator was irked by how fans had cracked his mystery box with so little effort. He repeatedly bemoaned the practice in interviews, alleging it ruined the experience for others, and as Season 2 developed his core drive appeared to be to write a new story that the fans wouldn't guess. This unquenchable distaste for this small-but-key part of Westworld fandom reached the apex when, in the lead up to Season 2's premiere, he trolled the internet by saying he'd spoil the entire show to preserve the experience free of guessing, then releasing a highly elaborate Rick Roll. It may be a funny gag - and the video does tease certain reveals - but it also suggests how dominant Nolan's dislike of this set of fans is.

Westworld Broke Itself Trying To Be Unguessable

Now, this reaction is understandable to a degree. Westworld knows it's "smart" and so wants to deliver the purest version of that - which, when dealing with twists, comes from a successful rug pull. Additionally, Nolan's experience with twisted narratives comes from less-mainstream shows like Person of Interest (that thus have a less-sizeable fanbase) or movies like The Prestige (where there's no time to speculate on the turn); the latter even preaches wonder coming from the trick. Westworld Season 2 is thus, from its very first episode, made to correct the "mistake" of Season 1 being guessable; a mistake that wasn't actually a problem.

It was so focused on making sure the obsessive one percent couldn't guess where it was going that it lost sight of everything else. Storytelling devices that had been carefully integrated in the first year were pushed to their extreme as anything approaching genuine evidence was backloaded and entire narrative diversions were introduced to throw off the scent (see everything in and around Shogun World). Looking back over the season, for everything that gains new meaning (future Charlotte is really Dolores in a replica body), there a counter clue that has next-to-no purpose in the story and is there just to distract.

This is why Westworld Season 2 was a chore despite making sense; the big picture was purposely and inorganically obscured. The characters always knew substantially more or less than the viewer, so there was no entrance point. The resulting conversation was unsurprisingly weak, with any theories springing out now incredibly broad and not awfully developed from the hiatus: Was Dolores still on a narrative? Is William now a host? Nolan tried so hard to ensure the show could not be guessed that he made it utterly unwelcoming.

What's happened to Westworld isn't just unclear multi-season planning or naked doubling-down of what worked before. It's being hyper-aware of the fandom to the point what worked and failed is skewed, then overcorrecting with that in mind. It's not dissimilar to Sherlock's Season 3 & 4, where Steven Moffat began playing with the show's online fandom to the point that what had initially been a modern-twist on Arthur Conan Doyle classics lost all sense of realism or telling simple mysteries stories. The biggest difference is that Westworld went the other way: the show didn't buy into the hype, it tried to fight it. It had to be smarter.

Conclusion: Westworld And The Prestige

At the end of The Prestige, which Jonathan Nolan co-wrote with his brother Chris, it's revealed that the two warring magicians played by Christian Bale and Hugh Jackman have both been living twisted dual lives to become the best. However, the pair are still ideologically opposed. Bale believes that art is for the artist - "sacrifice, that's the price of a good trick" - but Jackman is more beady-eyed:

"You never understood why we did this. The audience knows the truth: the world is simple. It's miserable, solid all the way through. But if you could fool them, even for a second, then you can make them wonder, and then you... then you got to see something really special. You really don't know? It was... it was the look on their faces..."

The film's overall conclusion is that neither way is intrinsically wrong - art cannot belong to just the viewer or the creator - but either is self-destructive if followed to its extreme; both characters lose so much in their quest of violent one-upmanship. With Westworld Season 2, Nolan ascribes all too readily to Jackman's monologue, believing that the only way to conjure wonder is to completely wrongfoot the audience.