Vice's ending and post-credits scene reveal just how much smarter the movie (incorrectly) thinks it is than its audience, utterly undermining what could have been an on-point takedown of former Vice President and all-around schemer Dick Cheney with a sense of contempt.

Starring Christian Bale as the man himself, Amy Adams as wife and motivator Lynne Cheney, Steve Carell as Donald Rumsfeld and Sam Rockwell as George W. Bush, Adam McKay's latest film charts five-decades worth of American history in a bid to unearth the true nature of Dick Cheney's crimes, show how he was able to get away with them, and question the audience in how the country allowed it to happen.

Related: Screen Rant's Vice Review

Unfortunately, it only really gets as far as the first point; Bale's exemplary performance leaves no doubt how the quiet schemer was able to position himself in a hitherto sidelined seat of power, but its lackadaisical structure means any sense of real repercussions to or lasting effects of Iraq and the wider Bush Presidency are an afterthought. That said, it's in the final point - talk the audience - where Vice's real problems lie. As the movie nears its end and begins to make its grand point, it leaves viewers with some unsettling questions. However, they reflect more on the filmmakers than they do Dick Cheney himself.

- This Page: Vice's Ending(s) Try To Take Down Dick Cheney In The Wrong Way(s)

- Page 2: Vice's Post-Credits Scene Thinks It's Smarter Than You

What Happens In Vice's Ending (& Post-Credits Scene)

Vice's ending zips the audience through the fallout of the Iraq War, skipping anything from Bush's second term to deal with Cheney's "new heart", gained after a near-fatal heart attack from Jesse Plemons' narrator Kurt who's been shown impacted by various Bush administration events like 9/11 and the Gulf conflict. Dick bounces back and begins building daughter Liz for a life in politics, in the process having to approve targeting his other daughter, Mary, for whom he'd avoided engaging with gay marriage debates previously.

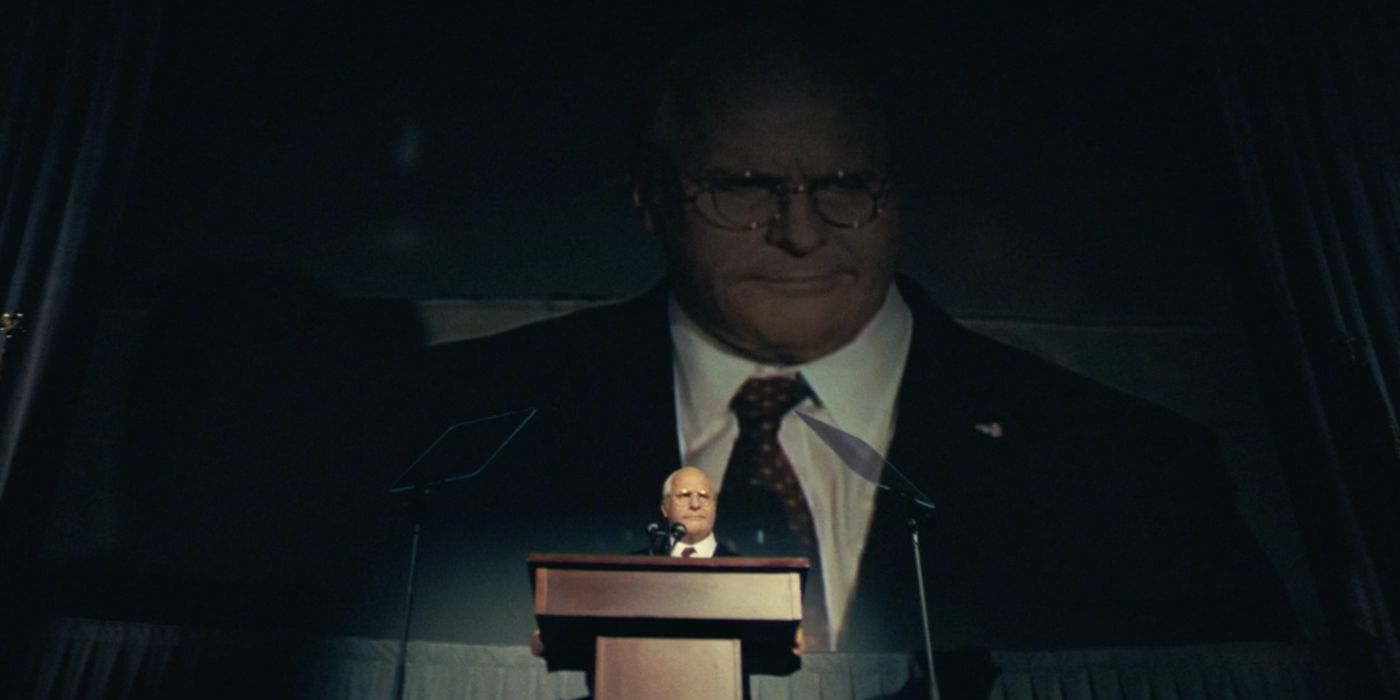

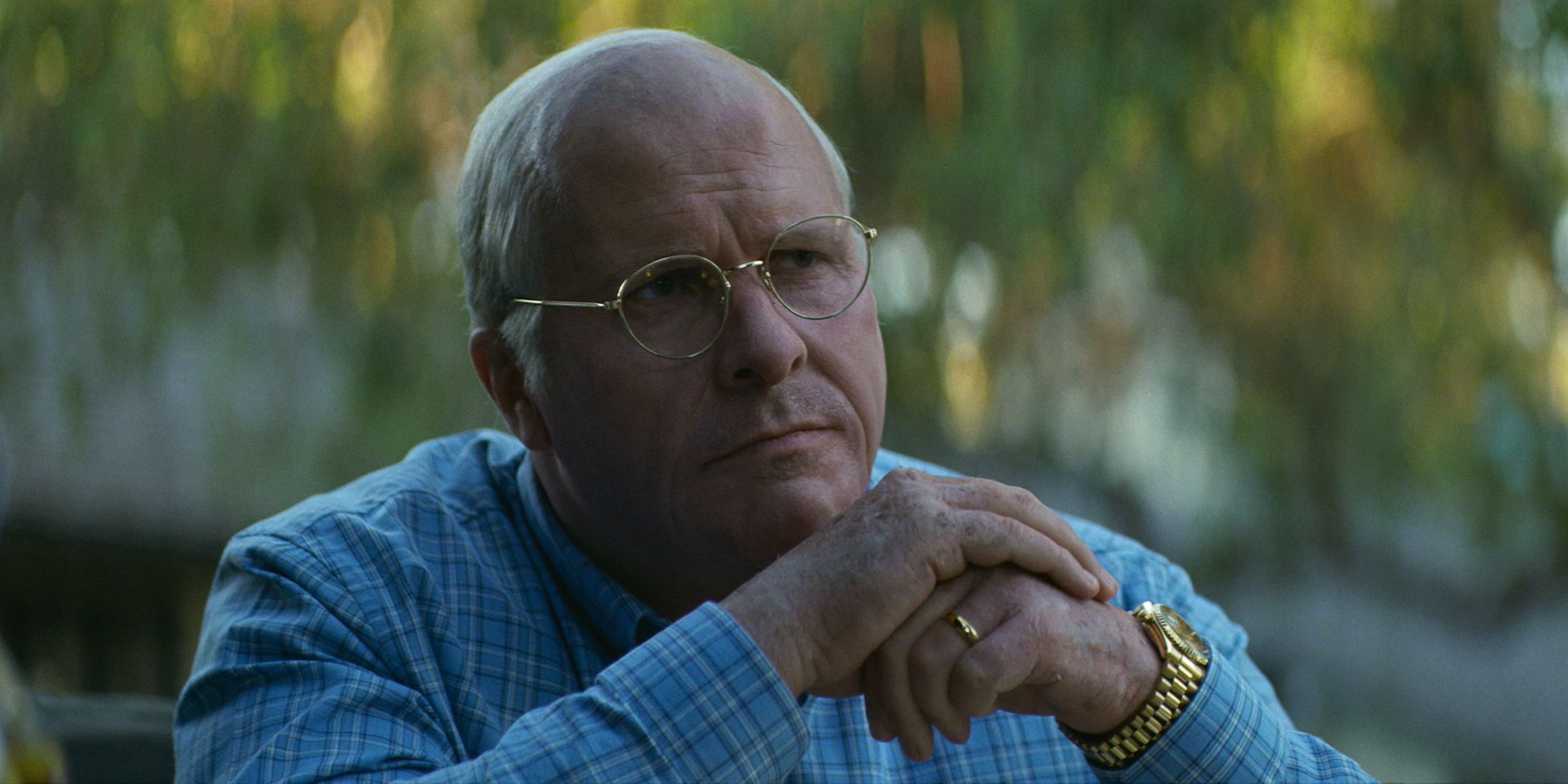

The movie comes to a close with an interview where Cheney defends his increasingly-controversial actions to the audience, with Bale speaking in real quotes that highlight an ultimate callousness and disregard for the American people and its interests. He believes he can do better for the population than they admit, leaving the movie on an aggressive note.

But that's not the actual end. Vice has a mid-credits scene that takes the film back to the focus groups where the Iraq War was developed, only with a meta twist: now they're discussing the movie itself. Here, the group falls apart over disagreement over whether it's liberal propaganda or scathing takedown, leading to fists. One disinterested member of the group turns away as the fight erupts and remarks that she's looking forward to the new Fast & Furious movie.

Vice's Ending(s) Try To Take Down Dick Cheney In The Wrong Way(s)

Vice is a film with a very clear goal: to highlight to a general audience that Dick Cheney was a bad person by way of his manipulative actions throughout his political life but specifically the Iraq War. To achieve this, it takes three distinct approaches at once.

Firstly, you have what could be best described as the "straight" biopic. This is the movie that Christian Bale put on health-threatening levels of weight for, that surrounds him with notable Academy favorites like Amy Adams, Steve Carrell and Sam Rockwell, and puts great efforts in recreating a heightened reality of the various White Houses of the tale.

The second is an exploration of Cheney's effect on the regular American people, primarily through the lens of Jesse Plemons' everyman. He suffers every step of the way, helpless to avert the course of history, and then in death unthanked helps further the cause. There's a sense of far-reaching impact and bitter helplessness. The film also makes efforts to use this to turn the attention to audience, making them question how they fit into all this, although that's less about direct influence than it is the third aspect.

That third aspect is the same trick McKay pulled in The Big Short, with comedic fourth wall breaks used to explain what Vice deems to be a complex situation popularly underappreciated to a mainstream audience. There are no literal cutaways to Margot Robbie in a bubble bath here, but there's plenty of times where the movie - outside of Plemons' voiceover - steps outside of its world to present the morally black choices in a way a viewer can understand and laugh at.

Individually, each of these methods has merit. In fact, any two of these combined could have led to a great movie: playing it straight with the Plemons twist gets to the emotional core of the message; doing an Oscar picture with The Big Short stylings creates a more comedic, fact-based approach; and the latter two more off-beat ideas lead to a film that spears Cheney with realism and ridiculousness in equal measure. But using all three only serves to undermine the film: Christian Bale's performance - especially his final to-camera conclusion - is rendered silly; Jesse Plemons entire existence comes across like another aside, an afterthought akin to Alfred Molina's torture waiter; and highjacking what purports to be a familiar movie with comedic fourth wall breaks actually makes what's a simple story hard to follow.

Taking on so much you lose focus is damaging to any film, but when a focused message is the entire point there's a serious issue. Much of what Adam McKay is doing in Vice is very well-done - the performances are Oscar-caliber, the threading of story turns effective, some of its jokes genuinely hilarious - but it's constantly working against itself. The ending fakeout, where halfway through the credits roll over a false reality of Cheney's 1990s retirement from politics, is pitched so perfectly in terms of placement and pacing that the movie's second half has to completely reset when it's trying to present direct causation. And Bale's final turn to camera is a method that thus far has been played for, if not comedy, joviality, making the intended impact feel cheeky; "I'm a bad person" becomes "Ain't I a stinker?"

Page 2 of 2: Vice's Post-Credits Scene Thinks It's Smarter Than You

Vice's Post-Credits Scene Thinks It's Smarter Than You

While Vice certainly has a confused messaging, it's only in the post-credits scene where the reasoning behind such off-kilter storytelling becomes clear. The stinger is a fourth-wall break akin to The Big Short stylings that at first seems to highlight how people react to Cheney's crimes today, something very in keeping with the various creative approach taken by the film. Except with its final joke at the expense of Fast & Furious, a new criticism arises.

As the militantly left and right-wing members of the focus group begin fighting, the apathetic, easily-swayed millennials immediately lose interest and want to watch what Vice clearly wants to present as mindless, escapist entertainment. There's already been much debate over what this means, but the clearest reading is that Vice's mid-credits scene is turning the lens to the American people - the system may be stacked against them and standing for what you believe in prone to aggression, but inaction perpetuates the cycle just as much. If not blame, they're very much complicit. It's also quite clearly a joke at "disposable" media, with a film angling itself at awards season contender throwing shade at one of the most profitable (and, in recent years, well-reviewed) franchises for providing such empty distraction.

This approach is rather insulting as is, but is made all the more so when it comes from Adam McKay. While now he may be an Academy favorite, having won Best Adapted Screenplay for The Big Short, his early career couldn't be more different. He's the brains behind Anchorman, Step Brothers, Talladega Nights and several other Will Ferrell vehicles. With no indictment of any of those films, few would describe them as high-brow productions; any intelligence lies in the careful delivery of jokes through a mix of scripting and improv, not the slow-burn exploration of themes. For him to now take aim at a film franchise that, like Anchorman, is regarded as a big crowdpleaser comes across as either oblivious or contemptuous; it indicates the director doesn't realize the true nature of his previous work or is actively ashamed of it.

Whatever the specific purpose in taking aim at Fast & Furious directly or purpose behind signaling a reliance on popular culture may be - and indeed whether Vice thinks it's an antidote to this way of thinking or just shedding light - it can only really come from one single area of motivation. Just as Cheney thought he was better than the American people, Vice thinks it's smarter than its audience. Its fatal flaw is that it isn't.

Vice Makes Cheney More Complicated To Appear Smart

Early on, in a bid to highlight how Dick Cheney grew in Republican circles, Vice points out how he was always quietly observing and calculating, plotting his next step while the manipulatable George W. Bush and Donald Rumsfeld dealt with the short term. It's the classic case of "the smartest person in the room is the quietest", something Vice's story would seem to ascribe to in critiquing a man who embodies it. And yet, the movie itself strives to prove its intelligence by being the loudest in the multiplex. It's a hypocritical approach and one that shows just how much hot air McKay is pumping into his recent films.

Both The Big Short and Vice have prided themselves in being populist entertainment that takes supposedly complex recent events and explains them to the layman. They break each case into its constituent elements, package them individually with famous faces who present a relatable metaphor, then assume they've done their job. But while doing this they neglect one key fact: the financial crisis and Cheney's plans for Iraq really weren't that complicated. Few people understand what exactly happened in either case, sure, but that's more from misinformation and bad explanations than it is genuine confoundment; a skilled expert on the subjects would be able to convey the key details to anybody without much difficulty.

McKay, evidently, is not a skilled expert. His chosen approach is one that believes a general audience won't be engaged with big vehicular explosions and treats them as such. It's not simplification, it's dumbing down. It's not accessibility, it's celebrity distraction. It's not explanation, it's obfuscation. What he's doing is making the situation harder to grasp; by repeatedly stating outright that it's really complicated and using time jumps and fourth wall breaks in a bid to half-explain it, he's actually undoing the ridiculous simplicity of his stories. And all because he approaches the material as if the audience would rather be watching Fast & Furious than "talky" movies.

-

There is a place for skewed presentations of history that aim to show the truth by altering reality. If every film about actual events was a stiff-lipped recreation, we'd learn nothing from telling the story. But those alternate approaches still need to have a clear goal with its storytelling decisions. The Favourite's dry presentation of Queen Anne's reign may not be for everyone but Yorgos Lanthimos' approach makes a strong point about power; and Roma uses Mexican revolution to frame an altogether more intimate story.

Read More: Roma's Ending: Real Meaning And Historical Background Explained

Vice has no such fair artistic reasoning. It makes a lot of strong creative choices yet mostly undermines them by a desire to frame the story not about reflecting on its subject but the smarts of its creators. It's the antithesis of the reserved Cheney, and sadly it just can't work here.