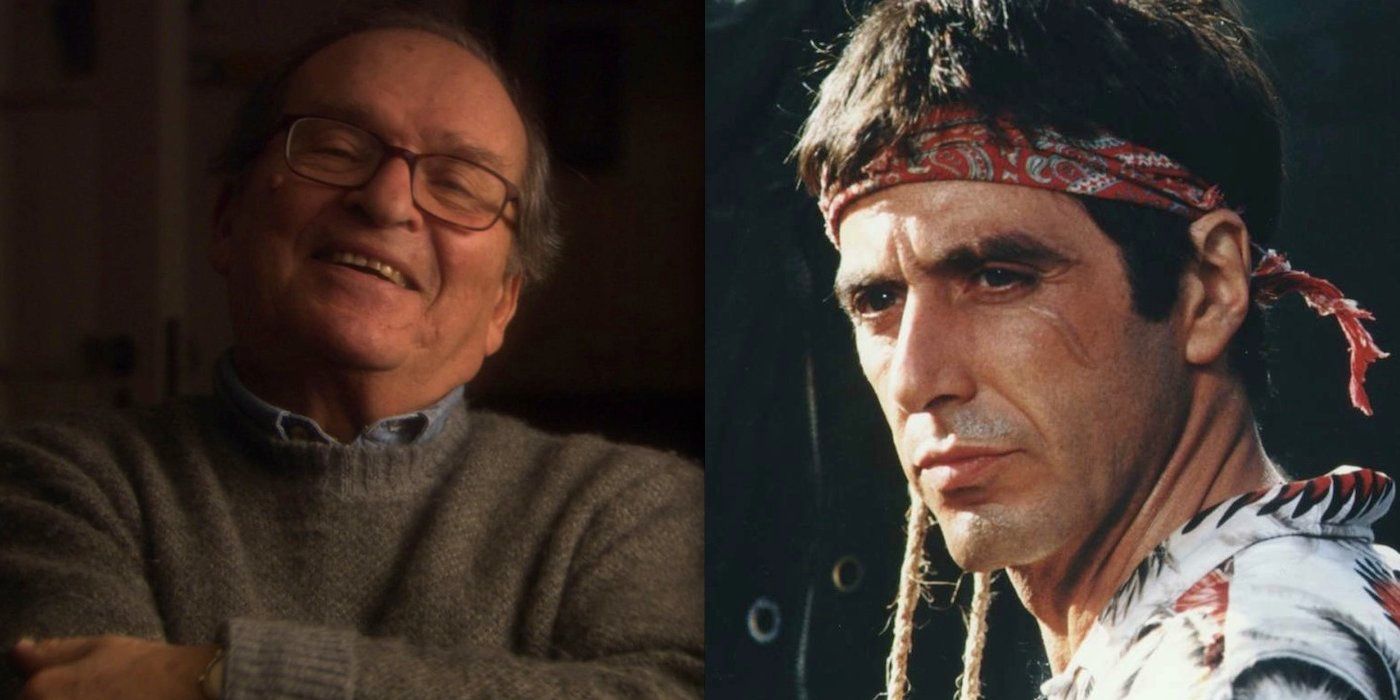

“Scarface wallows in excess and unpleasantness for nearly three hours, and offers no new insights except that crime doesn't pay.” These were the words that critic Leonard Maltin had to offer regarding Brian De Palma’s gangster epic, and he was not alone in his critique. Many felt the updated take on Howard Hawks' original lacked heart, with De Palma supporter Pauline Kael going as far as to observe that the “whole feeling of the movie is limp.” Suffice to say, a lot has changed since 1983, and the operatic saga is now considered a cinematic classic.

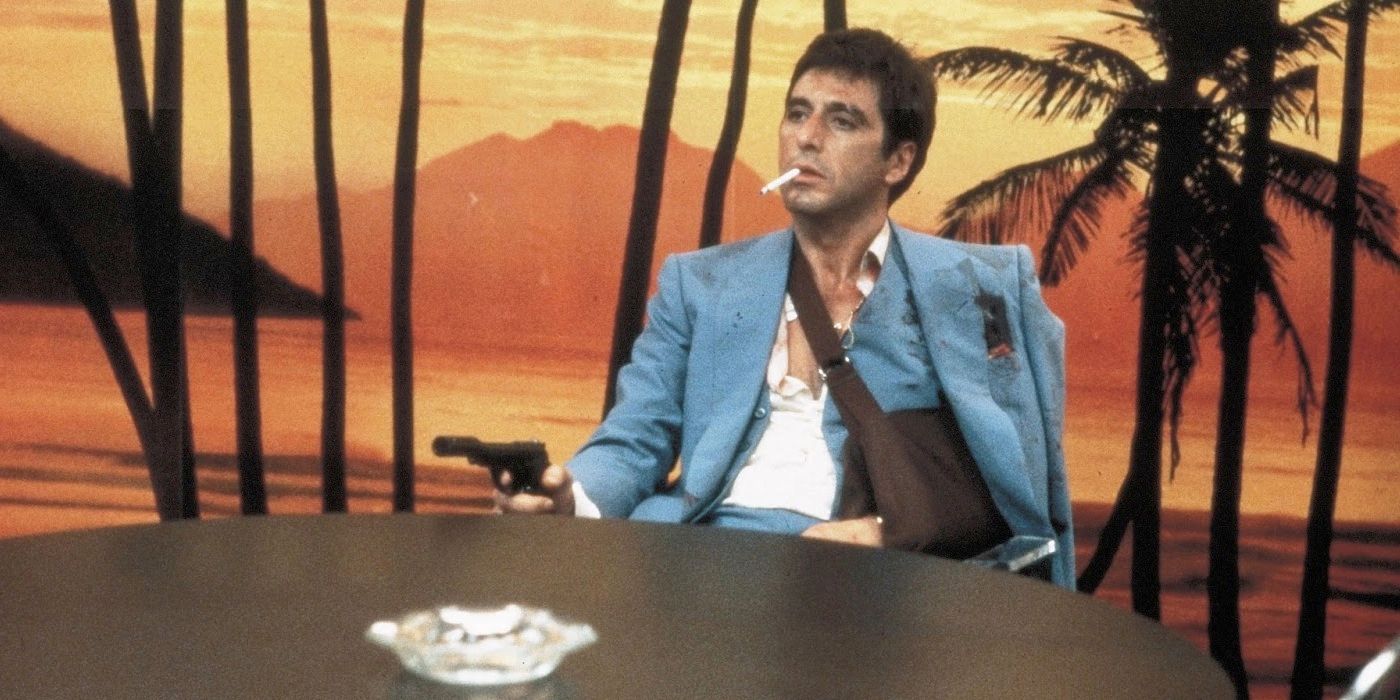

Influencing popular culture like few movies have since, Tony Montana (Al Pacino) and his peddling quotables are now commonplace among rap fans, crime junkies, and whoever else enjoys f-bombs set to Giorgio Moroder soundtracks (pretty much everyone). And though it's been three decades since Montana was last seen floating in his indoor pond, De Palma’s glitzy insanity and macho excess remains smoother than a cadillac with leopard print seats. We may not be able to offer up the world on a coke-white platter, but these historical tidbits prove just as addictive. The yayo of factoids, if you will.

Here are Screen Rant’s 15 Things You Didn’t Know About Scarface.

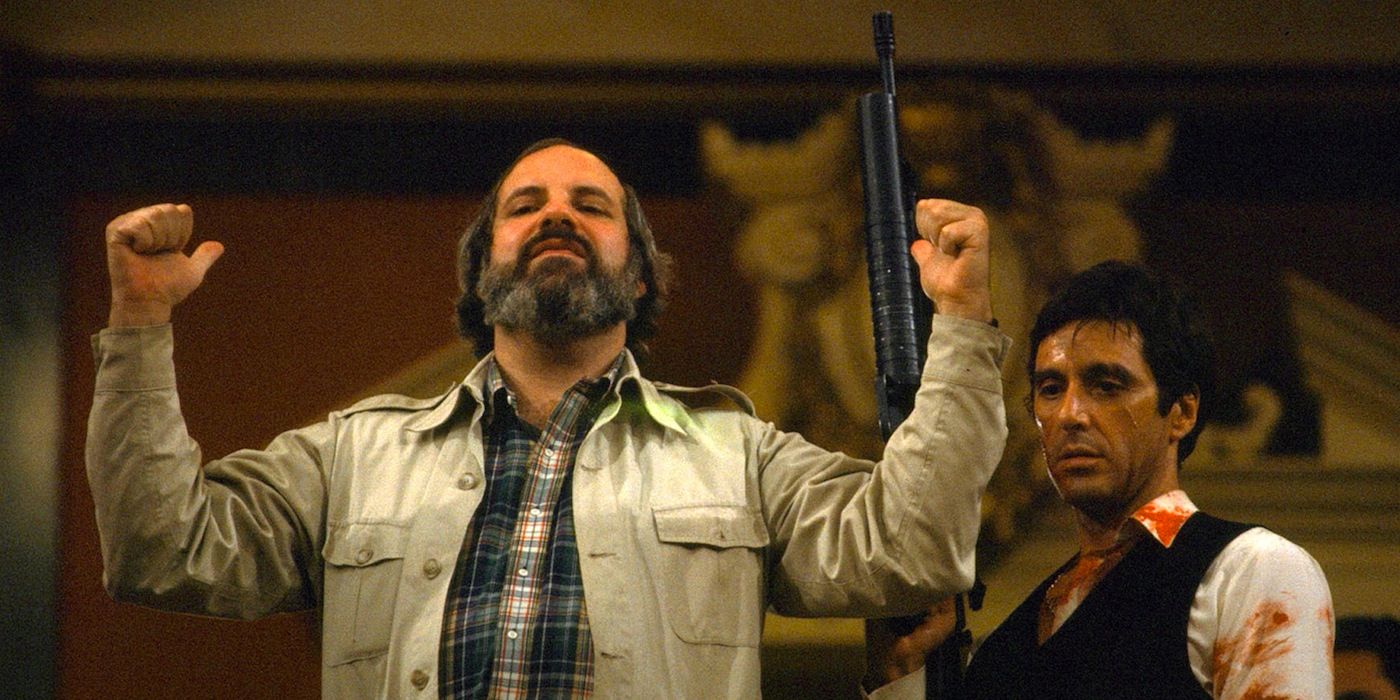

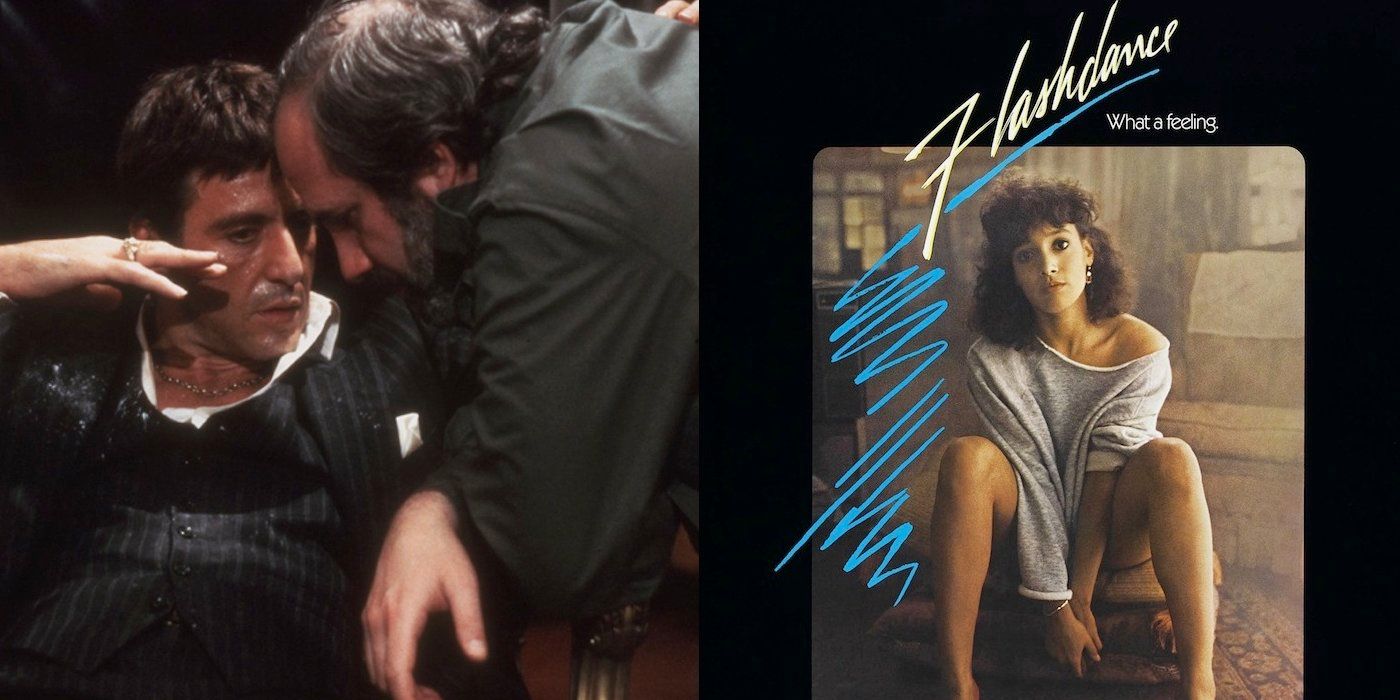

15. De Palma turned down Flashdance to direct the film.

Flashdance (1983) had all the hallmarks of an 80s classic: montages, teen romance, and a slinky Jennifer Beals sporting an iconic look. The story was catnip for any number of popular directors, but Brian De Palma’s erotic thriller resume (Obsession, Dressed to Kill) didn’t exactly place him atop the list. Despite this mismatch, producers Jerry Bruckheimer and Don Simpson specifically sought De Palma out, offering him the job within their first face-to-face meeting. The director, who had just bombed in his own thriller backyard with Blow Out (1981), quickly agreed to take the project despite it's uncharacteristic optimism.

Envisioning De Palma as the man behind Beals’ “Maniac” dance somehow takes on a darker edge; especially given what he had done to his teens in the past (Carrie, The Fury). Luckily, Scarface producer Martin Bregman met with De Palma around the same time, and a few exchanges later, the thriller expert left Flashdance duties to newcomer Adrian Lyne. Both films turned out better for it.

14. Nancy Allen and John Travolta were originally considered for roles.

Marriage is a divisive variable in the movie business. For Nancy Allen, who had gotten her break in the Brian De Palma horror classic Carrie (1976), it was a beneficial perk. The actress and director would wed in 1979, and go on to cultivate a fine working relationship through films like Dressed to Kill (1980) and Blow Out (1981). That Allen would be up for the Scarface role of Elvira Hancock seemed a given, but the failure of the latter project left De Palma with creative cold feet. He ultimately nixed Allen as a contender, and their offscreen union came to a close soon after.

Continuing in the vein of Blow Out’s blown opportunities, actor John Travolta was originally in talks to play Montana’s right hand man, Manny Ribera. All but washed up after the embarrassment that was Staying Alive (1983), Travolta needed a hit badly, and even met up with Al Pacino to discuss the role. Unfortunately, the arrival of Steven Bauer (the film’s only Cuban performer) killed any plausible chance for the actor, and he would have to wait around for Quentin Tarantino to revive his career with Pulp Fiction (1994).

13. Gina Montana makes her first appearance in the beach scene.

Around the film’s forty-five minute mark, Tony and Manny grab a drink at a Miami beach and begin discussing the future. Manny, the shameless womanizer of the two, can be seen carefully eyeing a girl from behind, clear as day. Paying little mind to the distraction, Tony goes about his megalomaniacal rants on paradise and vulgar comparisons. Before Manny gets Tony turned in the right direction, the pink bikini bystander has all but disappeared from sight - a very lucky break, given the woman’s true identity. De Palma has since divulged that the woman in question was Gina Montana (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), Tony’s sister and focal point of his uneasy affection.

Though never alluded to again, this skin happy debut was intended to be the first sign of Gina’s recurring promiscuity. It’s quite subtle, and serves to remind the viewer that De Palma can wield nuance brilliantly in the right situation. Scarface may be his most boisterous outing, but this nice addition proves that the director can subconsciously suggest with the best of them.

12. 42 people are killed in the film

It goes without saying that lots of people die in Scarface. The film basks in a universe of moral inhibition, where bullets and knives bleed out as often as insults and incestuous undertones. De Palma’s sadistic style rarely apologizes, either, converting human life into a checks and balance system that means little by the time Tony’s flame smothers over. This is where critics like Maltin and Kael critiqued the most--apparently seeing a guy get hung from a helicopter is not their idea of cinematic titillation. In defense of these unfavorable remarks, however, De Palma makes no attempt to conceal his intentions, going as far as to bump off forty-two people to prove his outlandish point.

Whereas modern films like The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) have shifted gears towards unfathomable death tolls (610), each murder in Scarface feels frightfully memorable. From Emilio Rebenga’s date with doom to Frank’s pitiful final moments, De Palma and writing cohort Stone prove that less murder can be more with the right amount of panache.

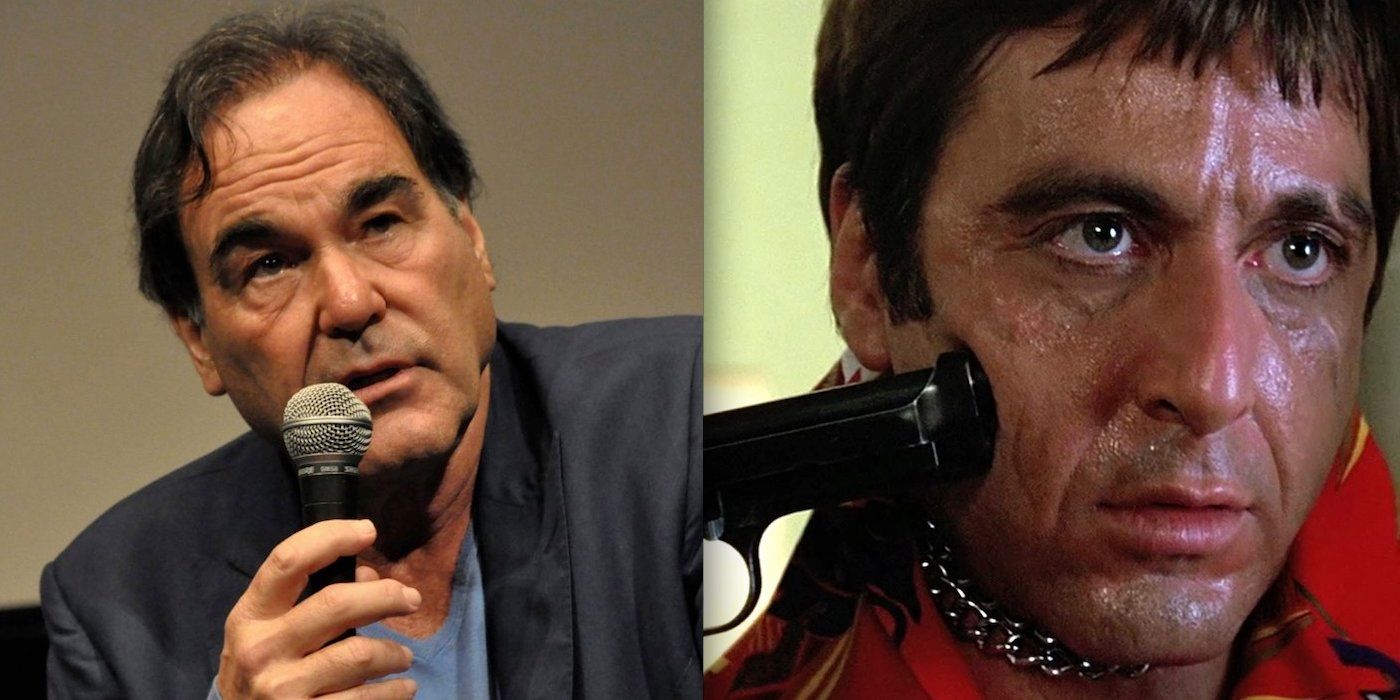

11. Oliver Stone based the script on personal experience.

Hired to revamp the original Scarface story, Oliver Stone decided it was time to kick his cocaine addiction once and for all. "I had been hooked for a year or two and I decided to kick it and I moved to France, which was the best thing I ever did," he explained to Total Film in 2003. "I cut all my connections to LA, had a new life and wrote Scarface in an apartment in Paris. I wrote it straight which was good because I don't think cocaine helps writing. It's very destructive to the brain cells. I think my writing was getting shallower."

The cold turkey approach proved important to Stone’s impending stardom (and health), though the excursions he experienced in the process would up birthing the film’s most hair-raising moments. The chainsaw scene, subject of heavy criticism upon initial release, was pulled from a real story dealing with Colombian drug pushers and their violent methods. Stone admitted to taking artistic liberties, saying it was “not done that way. I dramatized it,” but the air of desperation he captured remains eerily authentic.

10. Pacino requested cinematographer John Alonzo only talk to him in Spanish.

On all accounts, Al Pacino pursued the character of Tony Montana with reckless commitment. He insisted on working with experts in knife combat and personal trainers to hone a man that had, as he described it, “a certain lion in him.” Panamanian boxer Roberto Duran also aided this evolving presence, and served as a focal point for Montana’s swaggering Latin charisma. The real test, however, would be the language barrier, as Pacino not only needed to comprehend Spanish, but convincingly convey a thick Cuban accent. Co-star Steven Bauer coached the actor between takes, echoing cadences and implementing practice lines (“look at dem Pelicangs fly!”) that would up in the film's famous bathtub scene.

Barring the efforts of Bauer, Pacino’s greatest mentor would actually be behind the camera, in the guise of cinematographer John A. Alonzo. The Mexican cameraman behind classics like Harold and Maude (1971) and Chinatown (1974), happily obliged the actor’s onset request to only address him in Spanish. Pacino’s spirited portrayal sold many on his faux Cuban descent, proving Alonzo’s bilingual efforts were well worth the time.

9. Montana is only called Scarface once in the entire film.

The Scarface moniker is one of the few holdovers from the original that remained untouched. Logical, given that it’s the literal title of the film, but odd in that both men rarely acknowledge their facial lacerations. In the 1932 version, Tony Camonte (Paul Muni) is never actually referred to as ‘Scarface,’ unlike real life inspiration Al Capone, who gained the nickname at a young age. Oliver Stone’s version, modeled after Latino criminals like Pablo Escobar, follows in this sparring style, though with one exception to ensure his adaptation stood out.

For English speakers, Montana is never referred to or given the ‘Scarface’ mantle, sharing his predecessor’s affinity for a simple ‘Tony.’ That being said, the inclusion of the Spanish language throughout the film enables an offhanded henchman remark to land on the word ‘Caracicatriz,’ which translates directly to ‘Scarface.’ Buried amidst the drugs and women, it's an easter egg that Stone surely delighted in sneaking in for international audiences.

8. Robert De Niro turned down the role of Tony Montana.

Al Pacino’s passion for Scarface dates back to its very inception. It was Pacino who saw the 1932 original at the Tiffany Theater in Los Angeles, and subsequently contacted producer/agent Martin Bregman with the idea of a remake. From there, the duo met with Universal Studios, who expressed hesitancy towards one core selling point: Pacino himself. The future Oscar winner had every intention of playing the title role, but in a move not dissimilar to his tenure on The Godfather (1972), the studio simply didn’t see it.

Universal would offer the part to Pacino's Godfather Part II (1974) co-star Robert De Niro, who quickly turned it down to star in Martin Scorsese's The King of Comedy (1983). Pacino was rightfully restored as Tony Montana in the wake of this rejection, and the rabid actor would go on to deliver one of his most iconic performances. Admittedly, watching De Niro shovel through mounds of cocaine while copping a Cuban accent sounds pretty incredible, but there’s no denying Pacino was the right Scarface for the job.

7. Pacino improvised the drug slang “yayo."

A slang term for cocaine, ‘yayo,’ was often used in the Cuban community to avoid suspicion from the police. As such, the colloquial word went unforeseen by Stone and De Palma, who made no such note of it on the written page. Pacino came across the word while honing his Cuban accent, and chose to whip it out during Tony's first deal with Omar Suárez (F. Murray Abraham). Caught aback by the unfamiliar slang, De Palma took an immense liking to the term, and integrated it into the rest of the script. A little cultural authenticity never hurt, especially when dabbling in such a distinct sector of Central American crime.

Unsurprisingly, the term ‘yayo’ would soon finds it's way into popular culture, with particularly avid use in the hip hop community. Post Scarface, every rapper, from The Notorious B.I.G. and Nas to Raekwon and G-Unit’s Tony Yayo, has adopted it into the grab bag of street vernacular. Given this deep-seated influence, it's any wonder Universal attempted to re-release the film with a rap soundtrack in 2003. De Palma, steadfast in his Moroder soundtrack, refused.

6. Pacino and De Palma were apprehensive about casting Michelle Pfeiffer.

Elvira Hancock was a character that every young actress in Hollywood had their eyes set on. Excluding the already discussed Nancy Allen, the list of considered talent included Debra Winger, Karen Allen, Jamie Lee Curtis, Courtney Cox, Beverly D’Angelo, Dana Delany, Margot Kidder, and Jessica Lange. De Palma’s process for selection was lengthy, and several noted actresses were cut outright due to age or physical appearance opposite Pacino. Whatever the conditions, the director was thoroughly disinterested when the studio suggested Michelle Pfieffer for the part.

Having just appeared in the musical flop Grease 2 (1982), Pfeiffer drew immediate backlash from both De Palma and Pacino prior to auditioning. Perceived frontrunners at the time were Geena Davis, Sharon Stone, and Glenn Close, though Universal and producer Martin Bregman’s insistence eventually paid off with Pfeiffer's knockout portrayal. De Palma later admitted to being wrong in his assessment, while the supposed box office liability turned in a career with three Oscar nominations. Plus, some of the coldest dance moves on the planet.

5. De Palma and Stone refuse to reveal what was used for fake cocaine.

The million dollar question: what did they use for the drug? Scarface is surely one of the most snow friendly films ever made, as everyone and their lover seem to be snorting up between plot points. De Palma’s original plan was to use dried milk as the recurring prop, though screen tests proved underwhelming and the notion was soon ditched. Steven Bauer has since gone on record to suggest it was indeed powdered milk, but no one else has stepped up to confirm one way or another. In fact, De Palma and Oliver Stone have adamantly refused to reveal what the final recipe turned out to be.

The rationale behind this close chested secret lies in artistry - both men feel that to divulge would be to undercut the onscreen illusion. Over the years, however, a few different hints have suggested that real cocaine was used in specific scenes. Pacino has continuously toyed with this public myth, while De Palma doesn’t deny pulling the real deal for authenticity sake. As to how much, if any at all, was snorted, that looks to be a secret no one wants to share. Perhaps Michael Bolton has some answers.

4. Steven Spielberg handled one of the cameras in the final shootout.

Oliver Stone may have criticized “Spielberg for his view of exceptionalism,” but the director’s working relationship with Brian De Palma has always been strong. Both Steven Spielberg and De Palma hail from the 70s school of Movie Brats, a group of filmmaking friends that also included Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola. The iconic crew would often visit one another on set, share the same hub of actors (Harrison Ford, Robert De Niro), and slyly leave their two cents within each film.

As the culprit this time around, Spielberg visited the set during Scarface's climactic shootout, and De Palma thought the Jaws director should also got in on the action. Strapped up with a camera, Spielberg actually films the sequence opener, a low angle shot of the Colombians infiltrating the house. It's onscreen for barely five seconds, with nothing to suggest the hand of one of the world’s most famous directors, but the tidbit remains a fun addition to an already iconic finale.

3. Sidney Lumet was originally slated to direct.

Though De Palma was the first directorial choice for Scarface, his unhappiness with the original script led him to depart for Flashdance. In the wake of this decision, Martin Bregman opted to go with Sidney Lumet, the director behind classics like 12 Angry Men (1957), Serpico (1973) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Lumet’s relationship with Al Pacino was already well established through the latter two films, which squarely dealt with gritty, fact based drama. Unsurprisingly, with this grounded preference, the director saw Scarface as a political statement of sorts, and updated the story to reflect current cocaine and immigration issues.

Bregman and Pacino were both ecstatic over the changes, but Lumet ultimately dropped out over what he deemed to be “creative differences.” He wasn’t pleased with the verbose nature of the project, and ultimately left the doors open for De Palma to return with a fresh perspective. Still, Lumet’s significant input, particularly the Cuban angle, would prove indelible to the final product.

2. De Palma pulled a fast one on the censors.

As a director who often received backlash for his content, Brian De Palma knew his way around a censorship debate. This awareness proved especially helpful when Scarface was slapped with an X rating (NC-17 didn’t exist yet), and deemed unfit due to excessive violence and foul language. De Palma was forced to edit the film three separate times, but when each were rejected on the same grounds, the filmmaker brought in a group of law enforcement agents to testify to the accurate depiction of violence in the Miami drug scene. Operating under the pretense that such extreme content had educational value, the board relented and granted the film an R.

By that logic, De Palma argued the original cut of Scarface should also receive an R rating. Universal attempted to dissuade the idea out of fear there would be consequences, but De Palma went right on ahead and submitted his first cut to the censors. Nearly identical in content, the board didn’t even notice, and released the film as it was intended to be seen.

1. 207 F-bombs are used throughout the film.

When it comes to colorful language, Scarface is a masterclass display. Critics, quick to rally behind the banner of common decency, deemed it a tasteless touch, while viewers like Lucille Ball were rumored to have walked out in horror. F. Murray Abraham’s mom even got in on the bashing, requesting, “Can you tell Al not to use that language? He’s a big star! He doesn’t have to talk that way.” F-bombs are dropped a staggering 207 times, which, when aligned with the 170 minute runtime, equates to 1.21 F-bombs per minute. Even Elvira complains that there’s too much four letter fun going on.

It set the record for most F-bombs in 1983, and seemingly inspired a legion of foul mouthed filmmakers to up their game. Since Scarface, a flood of movies have surpassed it's F-bomb mantle: Reservoir Dogs (269), Goodfellas (300), and The Wolf of Wall Street (569) being among the most notable. 2014’s Canadian comedy Swearnet is the current record holder at 935 times, though, in the defense of quality, it’s also pretty terrible. Scarface, thankfully, retains it's classic quality. Plus, few movies have the luxury of an accented Al Pacino doing the honors. That is a f*%ing treat that will never get old.