Martin Scorsese once said that one of Stanley Kubrick’s films is equal to 10 of somebody else’s, because Kubrick packed so much meaning into the construction and composition of his work that even after 50 or 60 viewings, movies like Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut still can’t quite be figured out.

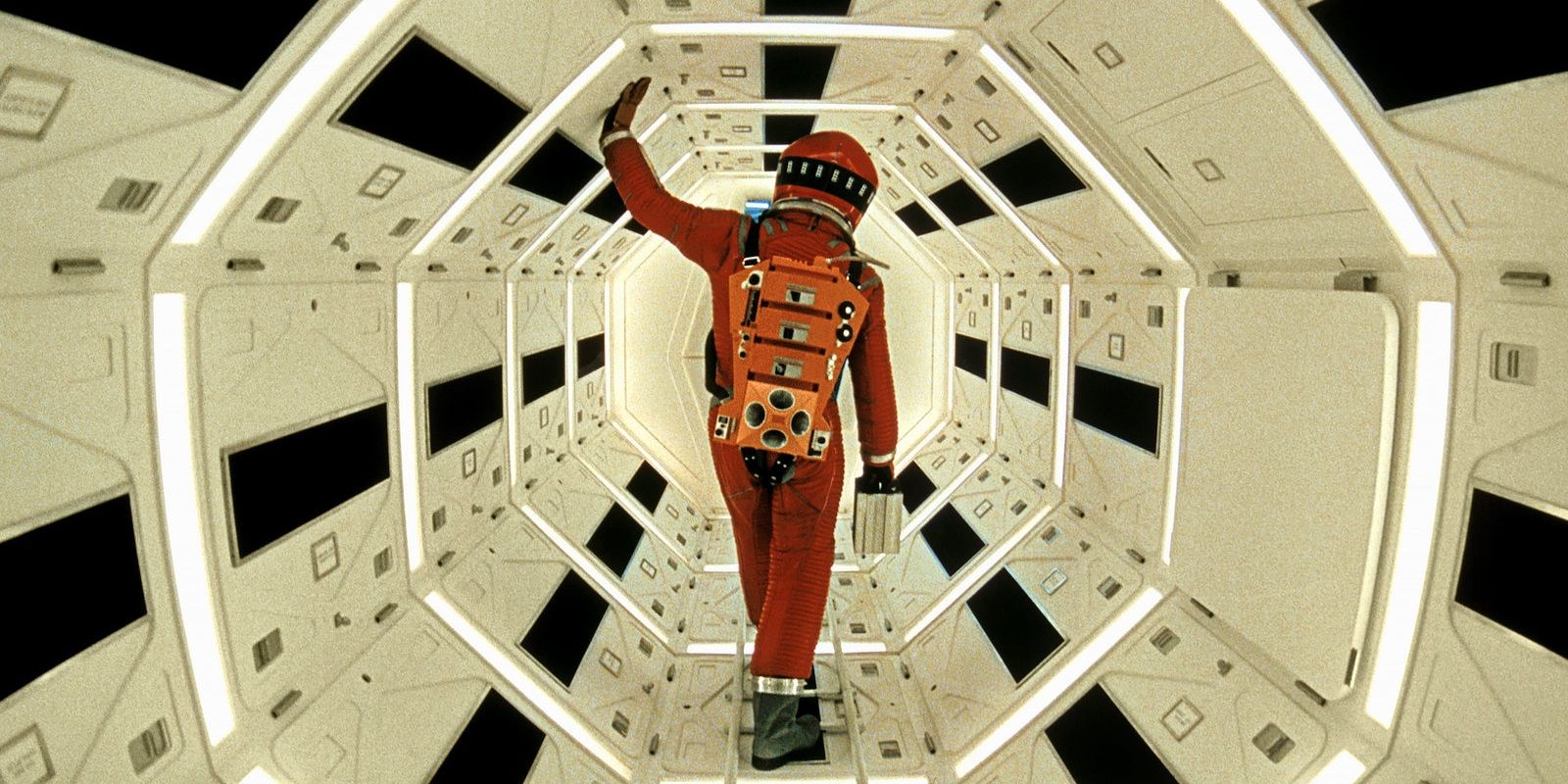

As a true epic following humanity’s journey from its early evolution to modern civilization to space exploration and eventually to the next stage of its evolution, 2001: A Space Odyssey is arguably Kubrick’s masterpiece. But there are plenty of alternatives in the director’s nearly spotless filmography.

2001 Is The Best: It’s Kubrick’s Most Influential Film

Many Kubrick films have inspired filmmakers, but 2001 is by far the director’s most influential work. A lot of young movie fans become attached to the art of cinema like a religion after their first viewing of 2001. Steven Spielberg has referred to 2001 as the “big bang” for a generation of directors.

Kubrick opened up new avenues for sci-fi cinema while perfecting the genre at large and creating the perfect science fiction movie. Everyone from George Lucas to Christopher Nolan has named 2001 as one of their formative influences.

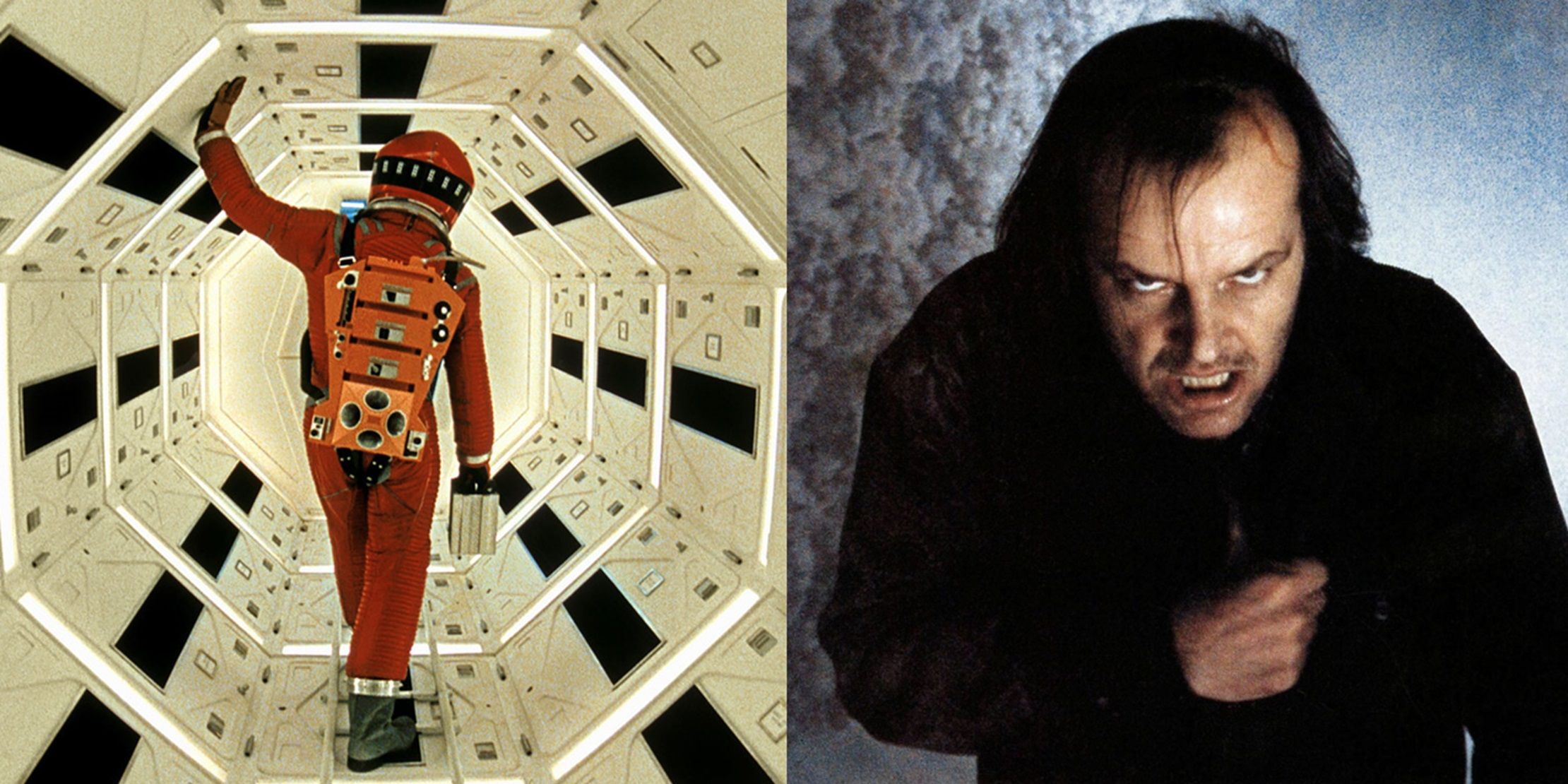

Alternative: The Shining

Stephen King hates Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of his bestseller The Shining, because the film has a completely different tone than the novel — but the cold, detached Kubrickian tone paired with King’s chilling premise to create a cinematic horror opus for the ages.

King’s Jack Torrance was a good man who was driven to kill by the demons in the Overlook, but Kubrick’s Jack (lifted to iconic status by Jack Nicholson’s mesmerizing performance) is much more terrifying: he’s a selfish jerk full of pent-up rage who’s driven to kill simply by being isolated with his wife and son and confronting how much he despises them.

2001 Is The Best: Its Meaning Is Open To Interpretation

Kubrick said that if there was one clear answer about the meaning of 2001, then he and his co-writer Arthur C. Clarke wouldn’t have done their jobs right. The movie has been dissected and analyzed by countless cinephiles over the past half a century and it’ll probably continue to be discussed just as fervently for the next half-century and beyond.

Rather than being used to unnerve the audience like the ambiguity in The Shining, the ambiguity in 2001 is designed to make the audience think. There’s real intellectual substance to 2001’s musings on technology and space exploration; it’s not all sci-fi nonsense.

Alternative: Paths Of Glory

Kubrick took to the trenches of World War I to tell the quintessential story of an individual’s tragically futile crusade against a corrupt institution. Kirk Douglas gives a captivating performance as Colonel Dax, who has to defend his men against a court-martial that could have them executed for cowardice because he withdrew them from a suicide mission.

The stakes are high and Kubrick keeps his lens focused on the characters and the emotions they’re going through during this unimaginably sinister ordeal.

2001 Is The Best: The Classical Music Juxtaposes Beautifully With The Space Exploration

Alex North wrote a whole score for 2001 that Kubrick famously discarded at the last minute and replaced with classical music, which had been his vision for the film all along. This must’ve been pretty heartbreaking for North, but based on the sound of the since-released score, it wouldn’t have been anywhere near as effective as Kubrick’s chosen compositions.

He plays an opera over the violent dawn of humanity, a waltz over the weightless rotation of a space station, and a symphony over the beginning of the next stage of human evolution.

Alternative: Barry Lyndon

Although some critics decry the painfully slow pacing of Barry Lyndon, others praise its cinematographic achievements in its use of natural light to make each frame look like a period-specific painting.

In many ways, Barry Lyndon is Kubrick’s Jackie Brown — a hugely underappreciated, unusually mature effort. They also both happen to use their protagonist’s name as the title.

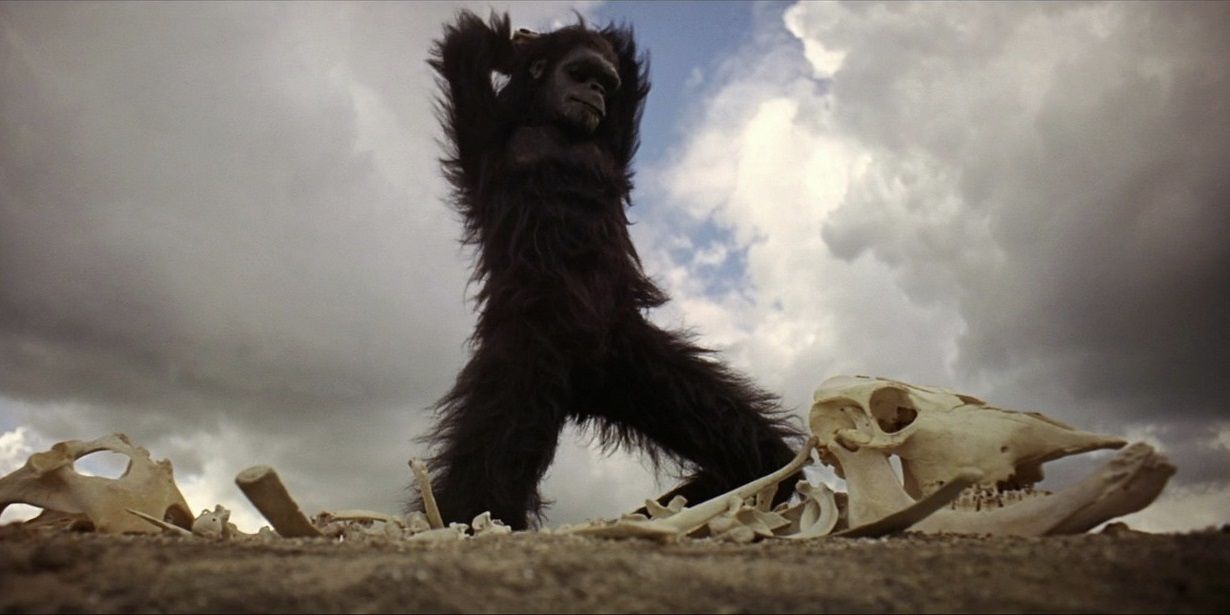

2001 Is The Best: It’s Kubrick’s Most Epic Work

Beginning with the apes that evolved into humans when they discovered violence and ending with a human being watching his life play out in minutes before moving on to the next stage of evolutionary existence, 2001: A Space Odyssey is a film epic in the truest sense.

Most of Kubrick’s movies are epics, from the world-ending destruction of Dr. Strangelove to the historic hero’s journey of Spartacus, but 2001 is without a doubt his biggest, boldest work. It’s the closest cinema has come to matching real epics like the Homer poem that the movie is named after.

Alternative: Dr. Strangelove

At the height of the Cold War, Kubrick helmed an incisive political satire that took jabs at both the United States and the Soviet Union. The director’s keen eye brings a great degree of visual comedy to the movie’s biting commentary, while Peter Sellers’ trifecta of lead performances cemented him as a comedic actor of Chaplinian proportions.

It also has one of the greatest endings in movie history: Vera Lynn’s “We’ll Meet Again” plays over the nuking of all life on Earth, the bitter irony being that the World War II-era optimism of Lynn’s classic has become obsolete since the dawn of nuclear weapons.

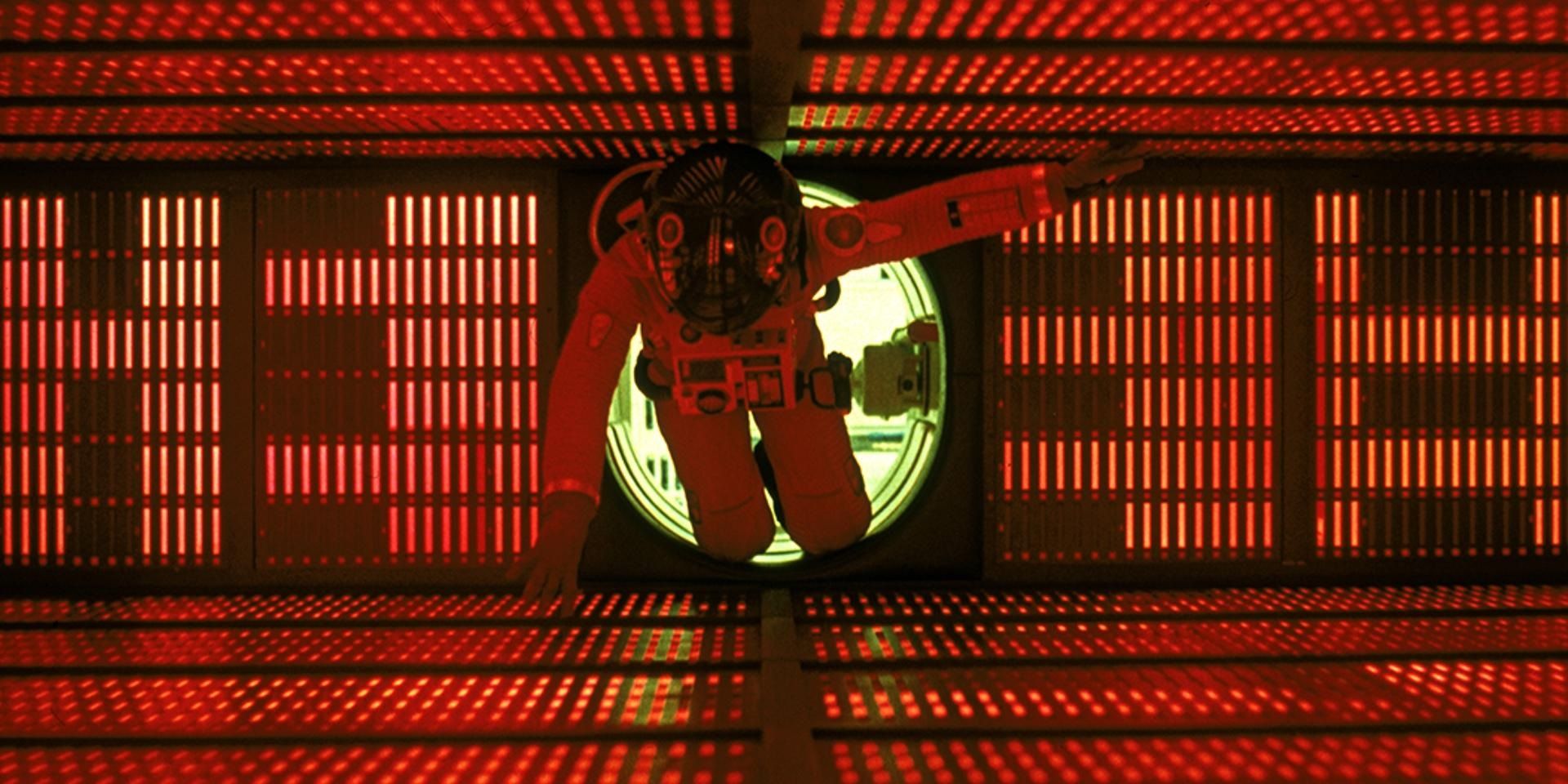

2001 Is The Best: It Was Decades Ahead Of Its Time

Technology actually caught up with Kubrick while he was filming 2001. The director wanted to cut the lip-reading scene for being unrealistic, but changed his mind when a computer was actually programmed to be able to read lips. Kubrick missed the chance to warn viewers about that, but he was ahead of the curve on a number of other things — particularly artificial intelligence.

The meditations on A.I. in 2001 are more hauntingly relevant as each year passes and real A.I. moves closer and closer to reaching HAL’s levels of cunning and sophistication.

Alternative: A Clockwork Orange

After the gargantuan production of 2001, Kubrick’s next project was a little low-budget movie shot mostly on location with no big effects shots. Adapted from Anthony Burgess’ novel of the same name, A Clockwork Orange tells the story of Alex DeLarge, an indifferent sociopath who attacks innocent people in their homes for fun.

At the midpoint of the movie, Alex is arrested and agrees to undergo an experimental rehabilitation therapy in exchange for a reduced sentence. In the second half of the movie, Alex is broken down and stripped of all personality. From the outlandish, bohemian style of future society to the Beethoven tracks playing over ultraviolent acts, the pitch-black comic sensibility of A Clockwork Orange makes it one of the most shocking and effective dystopian satires ever put on film.