Stan Lee should get an honorary Academy Award.

I’m saying that right up front because these kinds of opinion pieces tend to bury the lead and, since I’m writing this because thinking about it led me to bigger thoughts and a more important conclusion, I can already feel that happening. So it needs to be laid out here at the top: Stan Lee. Academy of Motion Picture Arts And Sciences. Honorary Oscar. Thing that should happen. I’m going to tell you why. Eventually.

The purpose of The Oscars as a showcase is not simply to gift the nominees and winners of awards with television time. It’s a mass-marketing presentation on behalf of the American film industry to show itself off to the audience and remind them why the ephemeral idea of “the movies” matters to them. Think about the building blocks of your average Oscar telecast, apart from the relatively limited amount of time actually spent giving and receiving the statues: Musical performances related to the nominated films. Retrospectives of beloved classics. Stage decorations recalling the (sanitized) circa-1930s glamour that’s universally understood as a signifier of “Hollywood.” Video packages of iconic movie moments. The red carpet. The reaction cam. The montage of those lost to us since last year. The most frequent repetition of the word “tribute” outside of a Hunger Games LARP.

For all of its deserved reputation as an often staid, overly-safe affair, The Academy Awards are one of the more delicate pre-production balancing acts in live-entertainment, walking a tightrope stretched between two difficult poles: Stoking happiness within the audience on one end, doing right by the industry professionals getting their accolades on the other. That’s why the idea of Leonardo DiCaprio (probably) having his Susan Lucci “It’s about time!” moment this year is so widely talked-up: Audiences love the guy ($100 million U.S. gross for what’s essentially The Passion of The Christ for bear-maulings?) and he’s a well-liked hard worker who’s more than earned the highest-honor of his industry peers. It’s the perfect Oscar Story – that kind that, if they could, AMPAAS would like to manufacture every year.

This brings us back to Stan Lee.

On the professional side of things, the people who get to stand up onstage at the Oscars, receive their gold statue and make a speech are supposed to have made a positive contribution to the film industry and to film artistry; which is a nice way of saying, “Somebody who’s made us a bunch of money in a mostly-respectable way.” People who make great films that nobody sees and people who make awful films that earn billions are equally unlikely to get there, while a widely-beloved figure whose notoriety comes from work that reflects well on the industry as a whole? That’s the ticket.

So if I were the person running the machinery at The Academy and I wanted to guarantee a moment like that at a forthcoming show? Getting Stan “The Man” Lee up onstage for an honorary Oscar, a standing-ovation and a speech would be an easier decision to make than my daily lunch order.

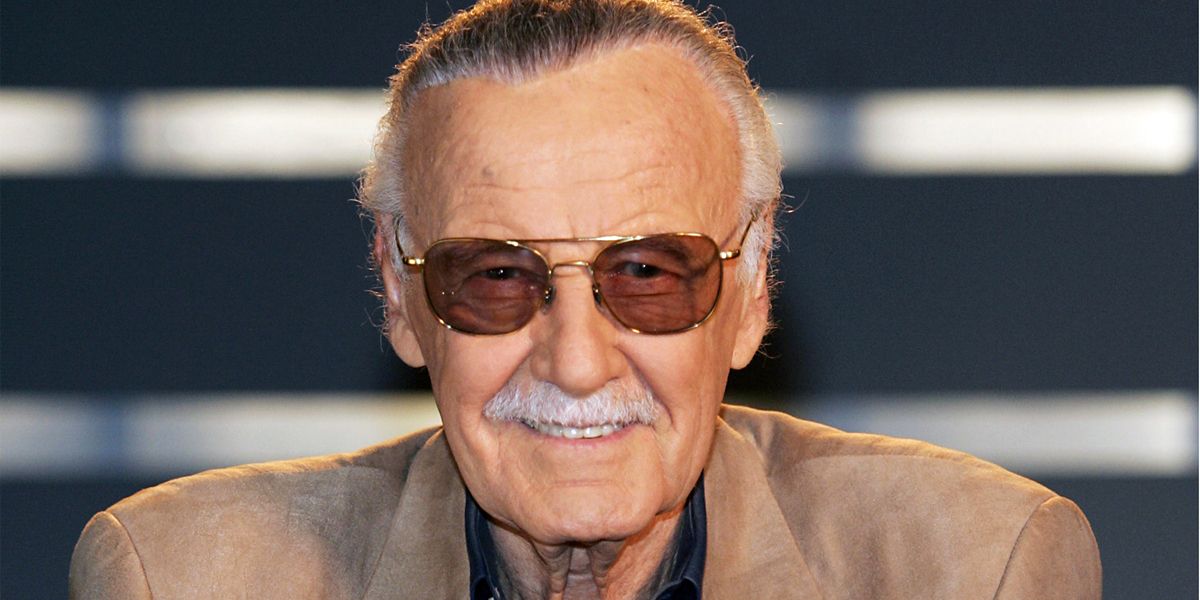

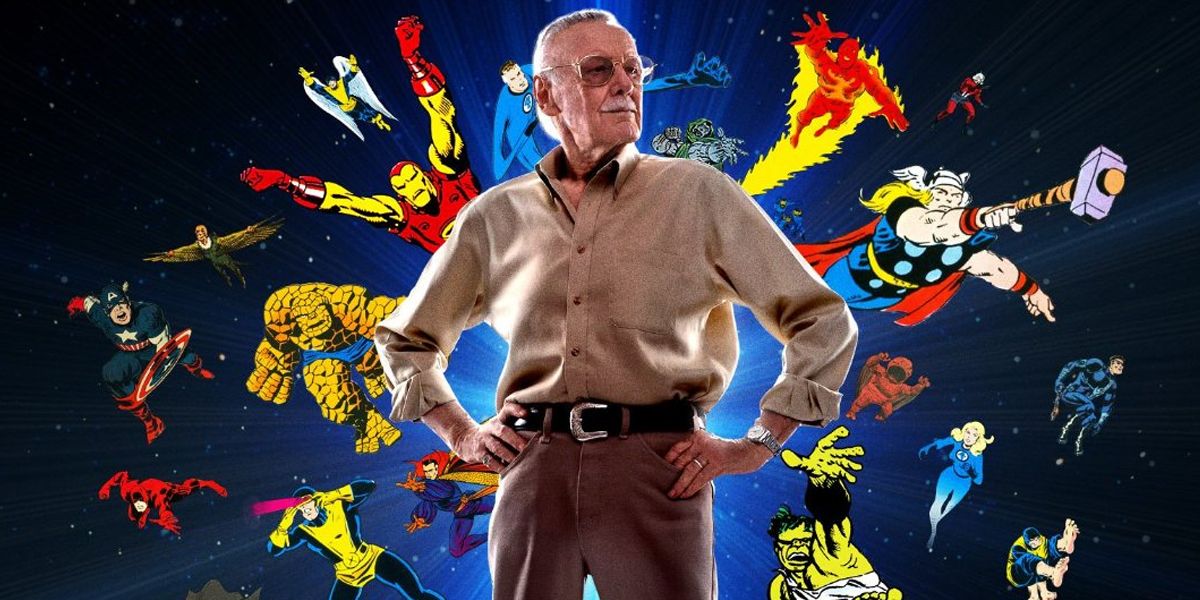

Going strictly by the part-of-the-industry/beloved-by-the-audience/made-us-a-ton-of-money equation, there are few figures in modern popular culture who qualify more readily. Particularly in the “beloved” part. Plenty of people in Hollywood are both more deeply-ingrained in the industry and more famous, but Stan Lee carries a particular kind of fame that we’ve pretty much given up conferring on human beings otherwise at this point. Stan Lee the person (that is to say, Stanley Martin Lieber, writer, TV personality, former president and chairman of Marvel Comic) may have his detractors, but as “Stan Lee” he has a public profile of the sort we used to confer on the likes of Walt Disney, Jim Henson and Dr. Seuss.

That he’s come to be ubiquitous to mainstream pop-culture where he was once a “celebrity” only in the so-called “geek culture” is incidental to the fact that both cases know him for the same reason: He was able to make himself a larger than life, flesh and blood “mascot” not simply for his own work or even his own company but for his medium. To the world at large, Stan Lee more or less “is” Mr. Comic Book Superheroes. And for over a decade now, comic book superheroes – in particular, heroes created or co-created by Stan Lee - have been carrying the film industry on their gamma-irradiated shoulders.

The film industry has not had an easy time of it in recent decades. The post-digital fracturing of the audience into millions of niches, the cultural challenges of globalism and the unprecedented competition for attention from digital platforms have rocked the Hollywood machine to its core. That fewer films are being made overall and studios are cutting back at multiple levels is a very real problem for the vast majority of people employed in the dream-factory who aren’t taking home Tom Cruise or Jeffrey Katzenberg’s pay.

To those people – the bit players, the readers, the fabricators, the electricians, the assistants, the craft service providers, the effects technicians, the makeup artists, the drivers etc. – superheroes, by virtue of being seemingly the only thing left that a plurality of the splintered worldwide audience can seem to agree on (at this point, Captain America is probably more respected globally than the actual United States of America), are saving their lives in reality just as assuredly as they are on the big screen. If The Academy was 100% brutally honest with itself and able to conjure imaginary figures briefly into physical reality (and I wonder which one would actually be easier…) at next year’s Oscar Ceremony they’d invite The Avengers, The Justice League and their mutual assortment of sidekicks and allies up onto the stage so that literally every other soul in the building could then take a knee and say: “Thank you, ostentatiously-costumed persons, for keeping all of our lights on and our hot water running.”

Obviously, they can’t do that. What they can do is invite an old man with an eclectic set of industry and industry-adjacent credits to his name up onstage to accept a statue and take a bow for playing a key part in creating, promoting and nurturing a set of characters and concepts that are at present the backbone of the business. If nothing else, it would certainly be appropriate; an ever-growing number of people in that room would have profoundly different careers right now if not for movies based on material said old man helped conjure into being. A trophy and some applause feels like the least they could do.

Going back to the “make the audience feel good” part of the equation, it’d be hard to beat as spectacle: A video package of money shots from the Marvel movies intercut with old photos of Lee and his (increasingly no longer with us) peers while famous face after famous face happily recall their first Stan Lee comic. An entire room full of celebrity swells on their feet applauding for an unassuming-looking 93 year-old gentleman who, realistically, could never have imagined this when he was doing the work he’s being honored for. It would be a huge moment – the emotional/symbolic equivalent of the world being able to publically thank Mother Goose for their childhood nursery rhymes.

So in terms of the audience-pleasing/”moment”-delivering aspect, it’s an easy call. That said, just because it would be a great show doesn’t necessarily mean it belongs at the ceremony.

Some motocross stunts would be entertaining too, some might convincingly argue, but The Oscars aren’t really supposed to be “about” motocross stunts – they’re supposed to be about honoring films and filmmakers. And giving Stan Lee or someone like him an Oscar, even an honorary one, is the sort of thing that could charitably be called “a reach” even though his TV hosting duties, producer credits and appearances as an actor make him more of an “active participant” in the film industry than many members of The Academy itself. There’s more than sufficient “justification” for doing it, in terms of whether or not Lee qualifies as part of the industry. But qualification isn’t the main objection such an idea, seriously floated, would run into.

No, the first and primary objection would be that “reaching” in the first place, for the purpose of awarding a uniquely beloved figure for something that hasn’t historically been regularly recognized (i.e. “Thanks for creating so much of what’s currently making us billions”) would somehow “cheapen” the image of Oscar itself. The Academy Awards, so the objectors would say, are supposed to be about merit over spectacle. It goes against the very point of the Academy Awards itself, in other words, which is a pretty convincing argument.

Unless you know your Hollywood History. Let’s be clear about this: The Academy Awards were never designed to tell you what the best movie of the year is, or who gave the best performance, or to make any kind of meaningful pronouncement on the quality of anything.

That sounds like obvious and smug, but it’s also a deeper truth. Yes, of course, there’s no determining an objective “best” when it comes to things like movies; but that’s an entirely separate issue. The point of the Academy Awards is not, despite the pageantry, arriving at some kind of arbitrary consensus as to who made the best movie or gave the best performance. That’s part of the pageantry. The point is for the U.S. film industry – “Hollywood,” if we’re being romantic about it – to put its best foot forward.

People were declaring this or that film the “best” thing they saw in a given period for as long as there was more than one movie to see, and various individual and collective entities had been giving out titles and prizes for about as long. But “The Academy” didn’t form until 1927, didn’t hand out their awards in a ceremony (and make it a news event) until 1929 and when they did it certainly wasn’t about celebrating film as art – hardly anyone would even posit “film as art” until the late-50s, and even less so in the business.

The same advances in communications technology that made it possible for the concept of “movie star” to translate into a global phenomenon also erased the once presumed concept of “public privacy” for those very stars. Everyday readers of newspapers and magazines in the tumultuous 20s had an endless appetite for the relatively new medium of gossip columns – the “leaked nudes on Twitter” of the pre-digital age – and its intoxicating promise of voyeurism with a moral-superiority chaser, and Hollywood’s high-living menagerie was giving them plenty to write about… some of it was even true.

But true or not, it wasn’t long before some of the writing was getting dark enough (look up the sad case of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle if you’d like to be profoundly angry for a while) that America’s other burgeoning brink-of-Depression vocation – The Moral Scold – was starting to threaten the bottom line. There were some fairly unpleasant solutions to this problem (behavior-clauses in star contracts, the Hays Censorship Code) but a pleasant alternative ultimately arrived in the form of The Academy and their Awards: Famous faces all dressed up for a night on the town celebrating happy announcements of positive-sounding accolades like “Best” this and “Best Supporting” that.

This is why so much of the complaining about perceptions of The Academy’s yearly choice of nominees being influenced by personal biases against certain genres (“Why don’t comic-book movies win Oscars!?”) or, more substantively, personal bigotry (#OscarsSoWhite) at the expense of rewarding for objective merit somewhat misses the point – or, rather, misframes the issue en-route to arriving at the (correct) point. The Oscars have never been about objective merit, and have always been about the industry putting forth an ideal image of itself via what it decides to call its “best” work. The problem is that they’ve gotten really, really bad at it.

The entire purpose behind this dog and pony show was supposed to be Hollywood showing its best face, but to do that you need to be keenly aware of what the people you’re showing it to consider a “best” face to look like. To suggest that a movie about a superhero or a space-alien be a viable Best Picture candidate isn’t to lower the standards of the award but to recognize that the standards of “genre film” have been elevated. To wish for a more diverse roster of nominees is not so much an unreasonable call for revolution as it is a perfectly reasonable request to recognize the evolution that’s already taken place in the culture The Academy inhabits.

Which brings us to another way the culture has evolved around The Academy – and why this is, ultimately, bigger than Stan Lee. There’s a myth that people tend to believe about Old versus New Hollywood because it “sounds true:” The notion that original ideas used to rule the business, and only now is everything based on something else. In raw numbers, this might even read as technically correct in as much as a higher rate of production likely meant more original material by volume; but especially in the realm of “prestige” filmmaking, screenplays based on books, Biblical stories, magazine articles, history, plays and previous films (The Maltese Falcon was the third attempt at telling its own story) were all routinely the subject of adaptation.

When you get right down to it, there’s not much substantive difference between making a movie out of a classic novel or the backstory of an episodic 1980s toy commercial (in the end, the caliber of the filmmaker is going to count for more than the caliber of the material). However, there is a pretty big difference between how it worked out for the material’s creators: When Old Hollywood turned to The Bible or the bestsellers list for inspiration, the persons who originally wrote it tended to be either dead by then or already fairly compensated. When New Hollywood makes movies out of comics or old toys? Not so much.

Transformers is a billion-dollar international brand, but whenever Paramount re-ups their contract with Hasbro the money goes right back to present-day Hasbro. The various people (mostly comic book writers, early on) hired to hammer out the Transformers mythology at the beginning? For the most part, they don’t see much of anything from it - at least not directly.

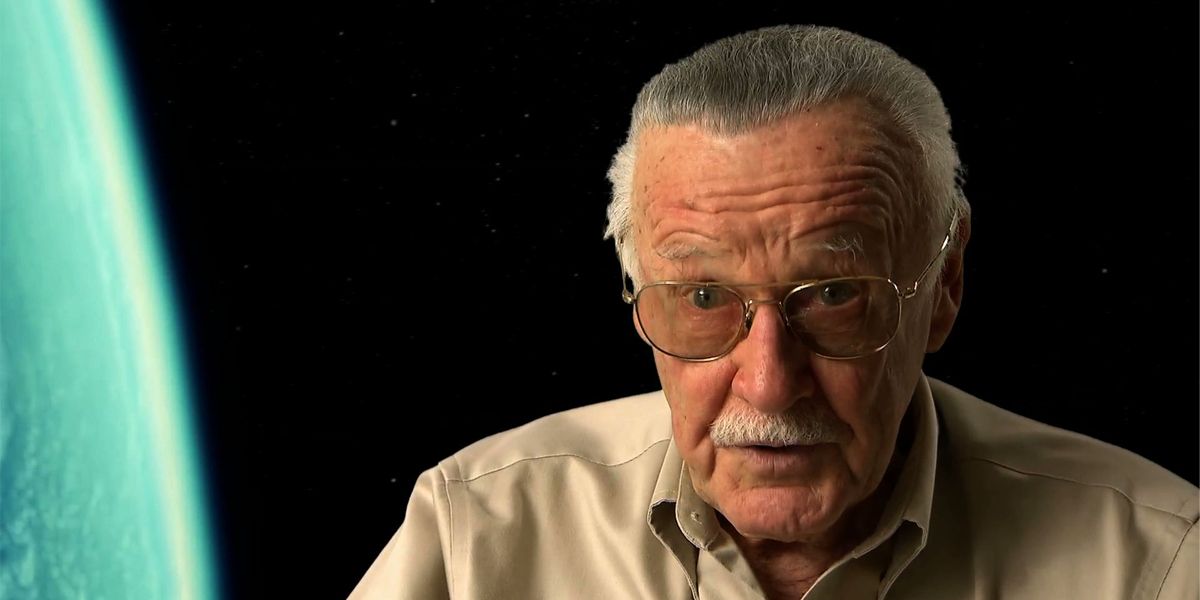

The more new franchises Hollywood opts to create out of established/merchandised intellectual property, the more stories there are going to be of men and women who did the heavy (creative) lifting early on to create characters, scenarios and whole universes not seeing a dime of the billions being made by re-writing their work. Even if you can set aside the questionable morality of how that works, how it looks is inescapable: It looks bad. Stan Lee made out better than a lot of his peers, and yet in an interview with CNN he explained that his executive producer credit on The Avengers was merely an honorary title. "I do not share in the movie's profits," he explained. "I just share in the interviews, in the glamour, in the people saying, 'Wow, I love that movie, Stan.'"

If the “brand era” of moviemaking is going to be the new normal for Hollywood, then Hollywood should be finding a way to more actively embrace the all too often shortchanged people behind the ideas that now make the studios rich - to, at the very least, invite them to share in the glitter, if not the gold. It’s logical, it’s just and it’s quite simply the right thing to do whether you’re talking about the industry’s public image or its very conscience.

The rationale and the justification are there. What’s needed is a mechanism.

The obvious flaw in this plan is that the so-called “Honorary” Academy Awards aren’t given at the main Oscars ceremony but at the Governor’s Ball a day earlier, which would negate the event’s ability to generate an all-time Oscar Moment in the form of the pop-culture audience seeing one of its central surrogate grandfathers take home a gold statue. The Lifetime Achievement Award is given on Oscar Night, but no – that one, absolutely, should be exclusively reserved for legends on the filmmaking side of the business.

My proposal would be that The Academy resurrect a variation on the Special Achievement Oscar, which used to be given to recognize some especially noteworthy technical contribution that demanded acknowledgement but didn’t have a category to be nominated in (it was discontinued after being awarded to the original Toy Story). “Special Contribution” has an appropriate ring to it, and the idea of such an award as a semi-annual event has a certain amount of appeal – especially when you consider who subsequent honorees might be (J.K. Rowling? Stephen King? Poster artist Drew Struzan?)

But I return to thinking about Stan Lee. I think about Stan Lee, in the mid-1970s, by many accounts angling hard to use his (relative) notoriety and connections from Marvel’s boom years to launch a second career as a Hollywood/multimedia player that never quite blossomed as big as he was aiming for. I think about Stan Lee, a decade before that, pulling a standard salary and working like a machine alongside Kirby, Simon, Romita and the other early Marvel folks pumping out big ideas on harsh deadlines; hoping to come up with some combination of costume, concept and nickname that would stick out on a newsstand or a magazine rack.

I think about Stan Lee, now in his 90s, watching The Academy Awards from home and – dependent on his level of engagement that late on a Sunday – being able (if he so desired) to pick out which actor’s designer tux, which actress’s jewel-studded gown and which party’s limousine was likely paid for in whole or in part with money made by “bringing to life” a concept or a story that he banged out on a typewriter half a lifetime ago (standing up, outside, changing position over the course of a day to keep the sun at his back according to some accounts) because it was his 9-to-5 food-on-the-table job.

And then, though I specifically try not to… I think about what it’s likely going to look, sound and feel like to be in a movie theater on opening night (hopefully many years from now) for the inevitable first time that a Marvel Cinematic Universe film includes a screen credit that reads: “In Memory of Stan Lee.”

Whatever else you might think of a modern Hollywood where the money, power and (likely soon enough) even the prestige are flowing from films based on comic book superheroes - the cultural spear-point of a world where Peter Parker is our Holden Caulfield, Tony Stark our Jay Gatsby and where Captain America might as well officially supplant Uncle Sam as the United States’ official symbolic representative - it’s where we are now, and where we’re likely to be for the foreseeable future. And if The Academy Awards fancy themselves as regaining some of their stature as the Golden Mirror reflecting a culture’s ideal image of itself, this is a reality they need to begin not just accepting but celebrating.

The Academy Awards traffic in symbolism writ-large, straining for pairings of honor and honoree that encapsulate the emotional zeitgeist of a moment in Hollywood time. That doesn’t need to mean handing Best Picture to an Avengers movie (unless, of course, one of them eventually deserves it…) but I can think of no more perfect a symbol for this particular moment in Hollywood history than the image of Stan “The Man” holding an Oscar.

So I say let’s make that moment happen.

Excelsior.