2020’s Netflix release Things Heard and Seen is based on Elizabeth Brundage’s novel All Things Cease To Appear, but the adaptation also owes a creative debt to Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining—but not the original Stephen King novel. Released in 1980, Kubrick’s adaptation of King’s novel was a contentious movie when it first arrived in multiplexes. The original author disliked how much the movie deviated from the source text, while many critics called it uneven, thrill-free, and disappointingly slow.

In the decades since the movie’s initial release, the time has been kind to Kubrick’s version of The Shining. The author has softened his initial distaste and admitted the adaptation has its merits(perhaps because King’s directorial efforts followed Kubrick’s cues and strayed from their source text). Critics, meanwhile, have come to view The Shining as a classic of horror cinema, and one of the most labyrinthine texts in the history of the genre.

There are so many readings of Kubrick’s The Shining that an entire documentary, Room 237, has been dedicated to expounding on various interpretations of the enigmatic movie. Despite this apparent impenetrability, The Shining has gone on to influence almost every horror movie made since its release in one way or another. For example, Netflix’s underrated 2020 chiller Things Heard and Seen is technically based on the novel All Things Cease To Appear by Elizabeth Brundage but in terms of theme, the movie borrows a lot of its story from Kubrick’s version of The Shining—but not Stephen King’s original novel.

Kubrick’s Shining Internalized The Overlook’s Ghosts

Much of what Stephen King took issue with from Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining was the director’s decision to make Jack Torrance a less relatable protagonist, with the famously cold and clinical director instead shutting viewers out of the character’s head. In Kubrick’s version of the story, the ghosts of the Overlook no longer represented Jack’s struggle with addiction, and thus his heroic self-sacrifice at the end of the movie was cut. Instead, a major reading of the movie suggests that, from The Shining’s recurring Native American art motifs through to the lavish Gilded Age parties that the ghosts hold, the Overlook instead came to represent an idealized version of America’s past that sweeps its bloody reality under the rug. Stephen King’s The Shining miniseries made the ghosts more outwardly and obviously scary to denote that they were a threat. Whereas, in Kubrick’s movie, they seduce Jack into seeing his family as the problem, seeing himself as a blameless paragon of decency, and making himself the threat.

Things Heard and Seen Uses Its Ghosts The Same Way

Jack joins in reframing the past’s evils when he becomes one of the hotel’s permanent residents in The Shining's dark denouement. Similarly, the brutally tragic ending of Things Heard and Seen sees James Norton’s unraveling academic murder his wife when his complex web of lies and deceit is uncovered, with the character asking for support from the misogynistic, murderous ghosts in his farmhouse to go through with the deed. The ghost assures him he needs to feel no guilt over his actions and his wife is at fault, much like the Overlook’s Lloyd and company reassure Jack that he’s doing everything right and his family is in the wrong. Unlike many Stephen King villains such as Pennywise and Randall Flagg, the ghosts of Kubrick’s The Shining and Things Heard and Seen appeal to the arrogance and self-centeredness of their targets rather than trying to threaten or scare them into compliance.

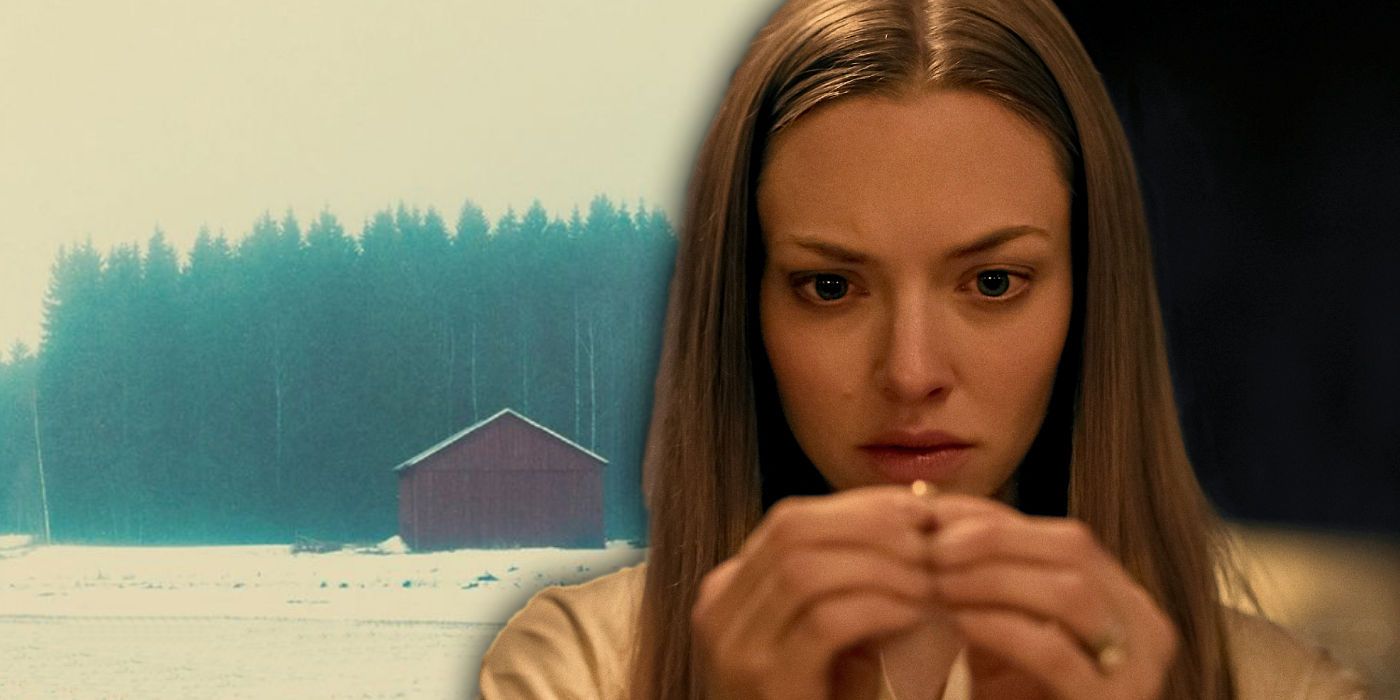

In Things Heard and Seen, the ghosts of the farmhouse materialize differently depending on who sees them, with Amanda Seyfried’s heroine seeing a protective female ghost where her villainous husband sees a violent male ghost. Again, the male protagonist is convinced to attack his family by an older generation of men who represent a more romantic image of how things “used to be,” much like Jack is convinced that it is his family who has gone astray and not him. The villain of Things Heard and Seen never addresses his plagiarism, lies, theft, and eventual murder, instead placing the blame on his wife, her friends, his employer, and anyone else within reach.

How Things Heard and Seen Uses Kubrick’s Shining Ending

The Shining’s sequel Doctor Sleep made the original’s ending even darker by cutting Jack’s moment of redemption from the source novel, and similarly, Things Heard and Seen has no interest in redeeming its villain. Where Kubrick's The Shining places Jack’s smiling face among Overlook guests and makes him part of their history, Things Heard and Seen places Norton’s conflicted villain in the same painting that he has been studying for years, as it becomes clear both characters were doomed to fulfilling their inevitable descents into madness and death. Both were always fated to their eventual demise and both are tragic figures precisely because they never knew their paths were leading to this hopeless, bleak end, but neither is granted a moment of redemption. Instead, both movies focus on the resilience of their respective love interests, whether through the literal escape of The Shining’s Wendy or the more metaphorical victory of Things Heard and Seen’s heroine who, like the heroine of Promising Young Woman, exposes her husband’s crimes to the world from beyond the grave.

Why Things Heard and Seen Borrowed From Kubrick (& Not King)

Stephen King’s original novel The Shining is surprisingly sympathetic toward Jack, and the character is painted as a tragic antihero who can’t help but succumb to his vices despite his best attempts to do right by his family. Both Kubrick’s The Shining and Things Heard and Seen tell the story from his wife’s point of view, re-contextualizing the tragic but helpless figure as a dangerous monster capable of real death and destruction. Both readings of the Jack Torrance character are valid, but the villain of Things Heard and Seen is more unambiguously irredeemable. Between stealing his dead cousin’s identity and artwork, constantly lying, cheating on his wife, murdering her, murdering his employer, attempting to murder his colleague, and possibly murdering the aforementioned cousin, he is far more dangerous than The Shining's lead. However, both characters are nonetheless seduced into attacking their own families by a ghost that promises them a return to an idyllic past that never existed, meaning Things Heard & Seen’s tragic tale takes inspiration from Kubrick’s version of The Shining even without the redemptive aspect of Stephen King’s original novel.