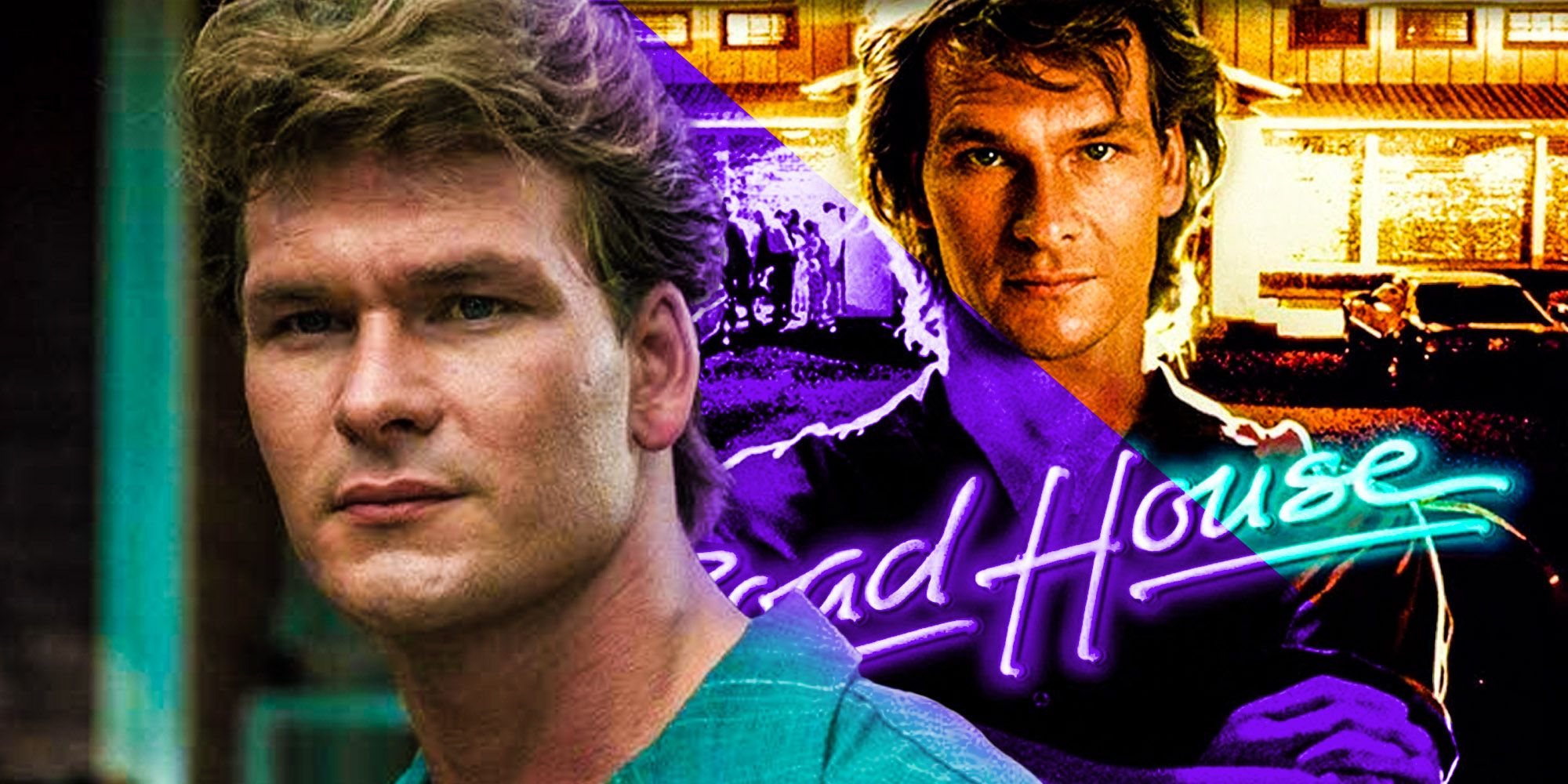

The 1989 action film Road House is a deeply philosophical movie - despite its reputation as a bone-headed testosterone-fest. Now recognized as a cult movie within the career of the late, great Patrick Swayze, Road House sees Swayze portray Dalton, a legendary bouncer who is brought in to clean up an out-of-control club called the Double Deuce in Jasper, Missouri. Before long, Dalton comes into conflict with Ben Gazzara's slimy villain Brad Wesley, who quietly rules over the entire town through his business manipulations.

As a movie predicated on bar fights, Road House actually has a lot to say about topics like anger, violence, revenge, and the basic trade of being a bouncer. Dalton is an exemplary bouncer less because of his fighting prowess (though he's highly skilled in that arena) and more because of his ability to navigate confrontations. When it comes to the philosophical undertones of Road House, Dalton's three basic rules of being a bouncer say a lot more than they've been given credit for.

Patrick Swayze, of course, had a natural gift for channeling cool and charming alpha males throughout his career, in everything from 1987's Dirty Dancing to Point Break. As Dalton, Swayze became a literal legend among bouncers, but despite its reputation as a dumb b-movie, Road House doesn't actually present Dalton as the killing machine the rest of the world sees him as. In Dalton's mind, once the fists starting flying, the battle has already been lost.

Road House Is About The Nature Of Violence

Summoned to clean up the ultra rowdy Double Deuce, Dalton's arrival is greeted by the employees of the club as the arrival of a legend and savior at the same time. Requiring a chicken-wire mesh to protect the band playing in the club, the Double Deuce's employees resign themselves to nightly brawls and are at the end of their collective rope by the time Dalton shows up like a gunslinger from a classic Western. By contrast, Dalton is cool and collected, telling his co-workers they'll be fine by simply adhering to his three rules, "Never underestimate your opponent; expect the unexpected", "Take it outside; never start anything inside the bar unless it's absolutely necessary", and above all, "Be nice", with the notable asterisk of "Until it's time to not be nice".

Dalton's rules show how clearly he understands the mindset of those who cause trouble in the Double Deuce or anywhere else. Though he frequently has to get physical to varying degrees with the troublemakers involved, he doesn't take it further than what is necessary to end the fight. In Dalton's words "Nobody ever wins a fight", and this is more than just a mere platitude on his part. As the film progresses, Road House shows that Dalton understands just how ugly fights can get better than anyone.

Dalton's Rules Are Important To Him

The rules Dalton lays out don't just come from his understanding of how best to de-escalate conflicts, but from the one time in his past when he had to use lethal force. Employees of the Double Deuce whisper to one another the legend that Dalton once ripped a man's throat out, but Dalton holds far more guilt than pride in his mythical lethality. Late in the film, it's revealed he had to resort to lethal force in self-defense after the husband of a girl he was with pulled a gun on him, with Dalton never having learned that the girl was married.

Though Dalton was acting within the bounds of self-defense, the movie shows that ending another man's life has weighed heavily on him ever since, with Sam Elliot's Wade Garrett urging him to put it behind him. Years after that horrendous encounter, Dalton's own firsthand experience with how far one might have to go during a fight is the foundation of his three rules. He doesn't want anyone else to have to live with what he does, and his rules are structured to end fights as safely as possible for every participant, and especially to keep anyone from getting killed. Of course, there always comes a point when "... it's time to not be nice".

Dalton Would Rather Be A Pacifist

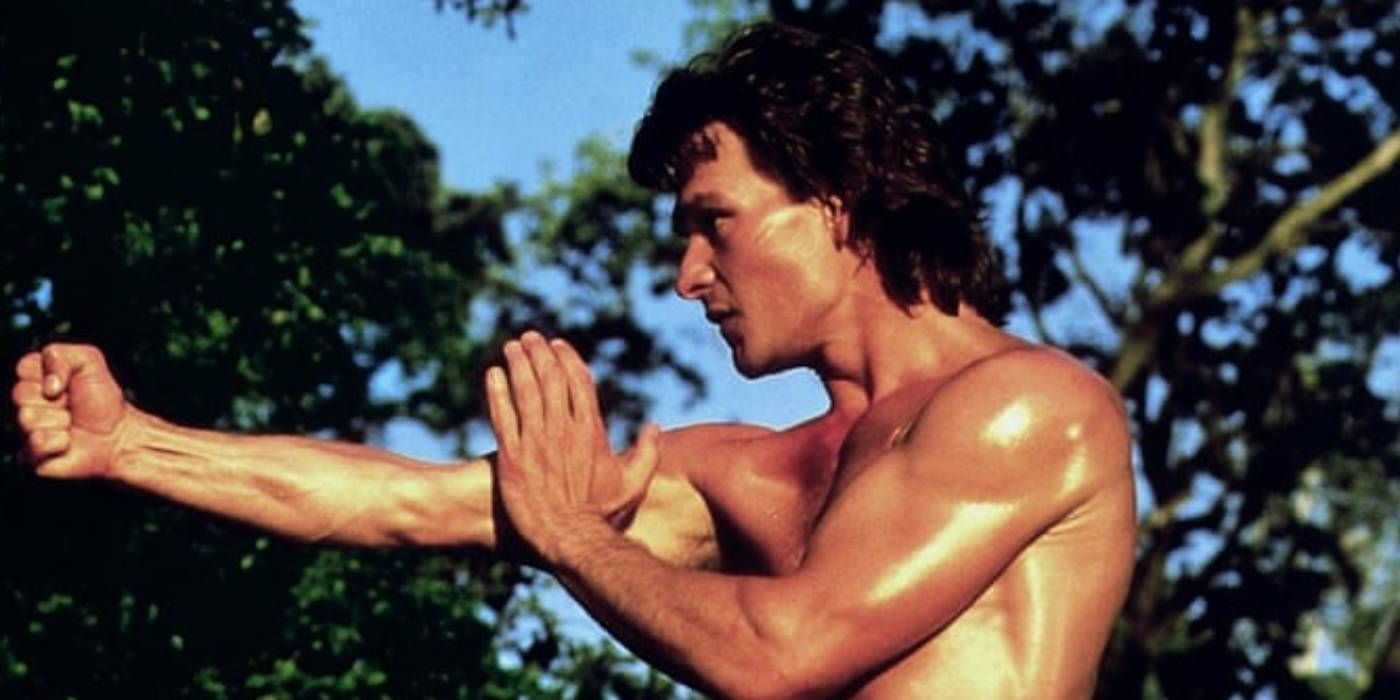

Despite Dalton's rules and the approach he takes to stomping out fights in the Double Deuce as quickly as possible, Road House shows he still has his limits when Wesley clamps down on Jasper. After being pushed to his breaking point, the legend of Dalton is given a bloody confirmation when he tears out the throat of Wesley's henchman Jimmy. As Dalton drags Jimmy's corpse into the lake and curses at Wesley watching from afar on the other side, his anger isn't just about the extortion Wesley has exuded over the whole town, or how much he has tightened his grip over it. Dalton's real source of fury is that Wesley has forced him to become a killer once more.

Dalton is pushed even further after Wesley has Wade killed, with Road House's finale seeing Dalton storming his house and eliminating his henchmen one-by-one. However, just as he has Wesley pinned down and is prepared to rip out his third throat, Dalton simply cannot bring himself to take another life. Wesley still ends up being put down by several of the local townspeople who arrive to come to Dalton's aid, and while Jasper may now finally be free of the tyranny of Wesley, it was a long, bloody path to get there that Dalton would rather have solved diplomatically if he could have.

As a channel surfing favorite in the years since it debuted in theaters in 1989, Road House has a reputation of being an enjoyable but simple-minded slugfest, but its mind is anything but simple. Underneath all of the testosterone and glossy 80's camp, Road House is about rage and violence on philosophical terms. The wise warrior that he is, if Dalton can't avoid a fight, he'd rather end it in the fastest way possible, his famous three rules showing how much he understands what unleashing all of his might really means.