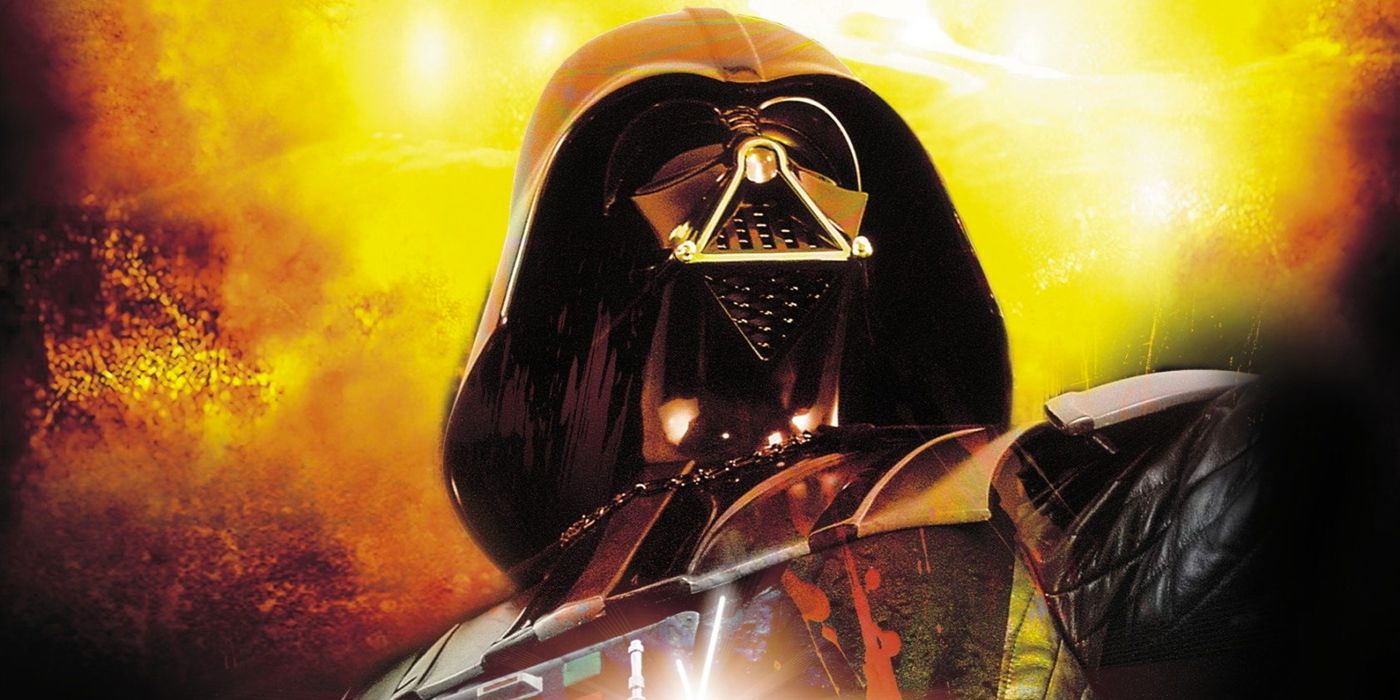

Anakin Skywalker's turn to the dark side in Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge of the Sith should stand as the greatest story in the series - as long as you can get past George Lucas' prime interpretation. 15 years after the final Star Wars prequel (and, indeed, last live-action film to creatively involved series creator George Lucas), the reputation of the trilogy has a strange status. Initially reviled by a generation waiting decades after Return of the Jedi to see the origins of Darth Vader, they were nevertheless box office successes in the time and have since gained adoration as the inspiration for a galaxy's worth of memes and stand as an ideological cleanser thanks to their cohesive guiding plan in contrast to Disney's freewheeling attitude to the sequel trilogy.

Still, few would hazard that they are genuinely great films, even the objective best: Revenge of the Sith. Released on May 19, 2005, Episode III was heralded (as Lucas had been promising since The Phantom Menace's release in 1999) as the darkest of the series, the pivotal chapter where the angelic slave would transform through fear and anger into galactic dictator. It's the deepest of the prequels for sure, charting the end of the Clone Wars, fall of Anakin Skywalker, purge of the Jedi, rise of the Empire and, ultimately, literal birth of new hope.

Yet for all the maturity, as a movie Revenge of the Sith still falls prey to the problems of the prequel trilogy. Anakin Skywalker's fall to the dark side is a hastily edited back-and-forth between barely descript green-screen sets, with dialogue so wonky even Ewan McGregor can't hide a smirk when declaring "I have seen a security hologram of him... killing younglings." It's partly a story with too much to do in too little time thanks to the intentional unique conflicts of Episodes I & II, but also simply the product of an auteur with sensibilities regrettably dissonant from an audience.

And yet it directly birthed what can rightly be considered the greatest story in the Star Wars pantheon. Now, such a claim some may expect to be related to Star Wars: The Clone Wars, Dave Filoni's animated TV series set between Attack of the Clones and Sith that greatly expanded the titular conflict, Jedi of all levels of prominence and the faceless-yet-individual soldiers of the Republic. The final stretch of the recent season 7, collectively titled the Siege of Mandalore, came right up against the events of Anakin's fall, seeing Ahsoka take on Maul, then suffer under the might of Palpatine's Order 66, concluding the story that framed Anakin's fall in a clearer, even more tragic light.

But 15 years before Ahsoka buried her lightsabers, the real depths of Revenge of the Sith had already been laid bare by Matthew Stover's official novelization. Released on April 2, 2005, over a month before Lucas' movie hit, the book is now technically non-canon (although it tells the story of a key movie, the book paints a backdrop of the Clone Wars influenced by the Expanded Universe and most-definitely Genndy Tarkovsky's 2D cartoon), but nevertheless presents the most compelling take on Anakin's fall - and the series' ultimate message of hope.

How Revenge of the Sith's Novelisation Improves Anakin Skywalker's Fall

Revenge of the Sith's novelization is a fully-rounded epic tragedy, telling a galactic and personal story from numerous perspectives and elaborating on the true intention of every scene of the source movie while crafting unique subplots that connect and complicate the main narrative. General Grievous' kidnap of Chancellor Palpatine is carefully outlined as the first step of the final plan whereby Dooku will be captured and Anakin anointed the leader of a new dark Jedi Order. Padmé's flirtation with Rebellion in opposition to Palpatine's increasingly precarious power grabs (a subplot that was shot then all-but exorcised from the released film). The Jedi investigation in the mysterious Sith Lord Sidious, who drives them more obliquely than in the movies where he's namedropped in passing a handful of times.

Obi-Wan Kenobi, Padmé, Palpatine, Yoda, Mace Windu, General Grievous all get their own Game of Thrones-esque perspective chapters, with Stover calling upon George R.R. Martin perspective tricks to deepen character understanding in the action scenes before diving into more flowery creeds on what it "feels like to be" key players in the moment and forever. The uncertain nature of Force, the Jedi's self-destructive dogma, the political strife in forming an Empire and countless abstracts from Lucas' movies get justified exploration here.

Related: Star Wars Is Trying To Turn Darth Vader Into An Anti-Hero (And That's Very Bad)

But all of this is added value to what it does to Revenge of the Sith's flawed core: Anakin Skywalker. Hayden Christensen's interchangeably whiny and wooden performance can be defended in all manner of ways - it's the dialogue, it was intentionally evoking Mark Hamill from the original Star Wars - but what he and Lucas were really going for becomes achingly clear with Stover's words. Anakin is a war hero bordering on celebrity, single-handledly warding off Separatist advances in the outer rim and becoming a legend after saving Palptine. And yet that hides a deep-seated fear, one that's been with him ever since leaving his mother and personified by the image of a dragon at the heart of a dead star: as he keeps reminding himself in the words of a perhaps-too-distant Obi-Wan, "eventually, even stars burn out." By the time Palpatine starts whispering in his ear, the Jedi in their plot to draw out Sidious push him aside and dreams of Padmé's death haunt his nights, he embraces that deep-seated fear to become another being entirely.

Darth Vader is Anakin Skywalker, questioned first as an unknown power deep within him and yet ultimately and unshakable his very being. But despite "how it feels to be Anakin Skywalker, forever" being a life of physical and emotional suffering, the book manages to hone in on Star Wars' prime message. Fear and darkness are where Revenge of the Sith spends much of its time, expositing on the imbalanced fight the light side is going in. At the start of Part 1, Stover outlines the dark's real tricks: concealment, illusion and its embracing of the light's impermanence. It's a bleak assessment, but one that's incomplete. This is Episode III of a then-known six chapters, and Stover endeavors to frame the tragedy with that eventual victory. The final emotion of this prequel story is not one of loss, but one of hope. And more than the simple sense of hope, it's of possibility. Yes, stars die and darkness will always be there, but what remains on the side of good is love. And "love can ignite the stars."

Why Star Wars Novelizations (Used To Be) Such Great Stories

Typically, movie novelizations conjure up a particular image: a hastily thrown-together paperback filler that recounts the plot based on an early shooting script, with their value existing almost entirely in what deleted scenes may have made it through the publishing process. That was never the case with Star Wars. Back in 1976, the first media set in a galaxy far, far away was Alan Dean Foster's novel (ghostwritten as George Lucas) which provided a deeper dive into then in-development film. But with the prequels, the novels stepped up a level. They not only made clear sense of Lucas' often obscure storytelling, but they also deepened and embellished it to become singular works in their own right.

This is one aspect of the Lucas era of Star Wars that, while minor in the scheme of a multimedia empire, feels particularly lost under Disney. Today, the novelizations exist as an exercise to fill plot holes (or, in the case of The Rise of Skywalker's book, completely explain the story) post-release. This can be felt before even opening the front page in the release plan. In no world would Disney-owned Lucafilm release an overly-detailed version of their movie weeks ahead of its global premiere. This reflects the inevitability of Lucas' tale and how the mystery box style of Star Wars became more pervasive after it fell in the hands J.J. Abrams, but also spotlights how much of a collaborative effort the prequel stories were allowed to be.

Terry Brooks' The Phantom Menace and R. A. Salvatore's Attack of the Clones were both impressive in this regard (the former especially for its expunging on the Living Force, a concept mostly absent from the theatrical film), yet they feel almost scene-setting for what Stover achieves in Revenge of the Sith.

Revenge of the Sith Shows Why The Best Star Wars Works

It's unclear where the line between George Lucas' story and Matthew Stover's writing lies in Revenge of the Sith's greatness. The author was, of course, working off the director's blueprint, and much of the deepening can be found - albeit lightly - in the principal movie. The spiritual intentions of Star Wars are always something that's been softened in the journey to the screen by way of Lucas' story and scripting, and there's enough grounding to many of Stover's grander ideas in the creator's overall intent for the prequels. At the same time, the way the author reworks stilted dialogue, making it feel more human and imbuing it in meaning that would be lacking even with Oscar-winning delivery, and create poetic rhyming where there is none at face value goes a step beyond. It's both pure Lucas and elevated by another.

That idea is truly summative. Star Wars is undeniably the brainchild of George Lucas yet has flown so high thanks to the countless additional interpretations of his work. Whether that be Ralph McQuarrie's concept art, John Williams' score, Marcia Lucas' editing, Irvin Kershner's dark direction, Timothy Zahn's initial sequel novels, Rian Johnson's reflective deconstruction or Dave Filoni's serialized expansions, Star Wars at its best is defined by a creative lens filtering the core idea into something unique.

With that in mind, that a novelization delivered Star Wars at its best shouldn't be surprising. Indeed, given that was where fans (of an admittedly small number) first discovered The Adventures of Luke Skywalker, perhaps it's truly fitting that it took literature to bring out the real depths of Revenge of the Sith.