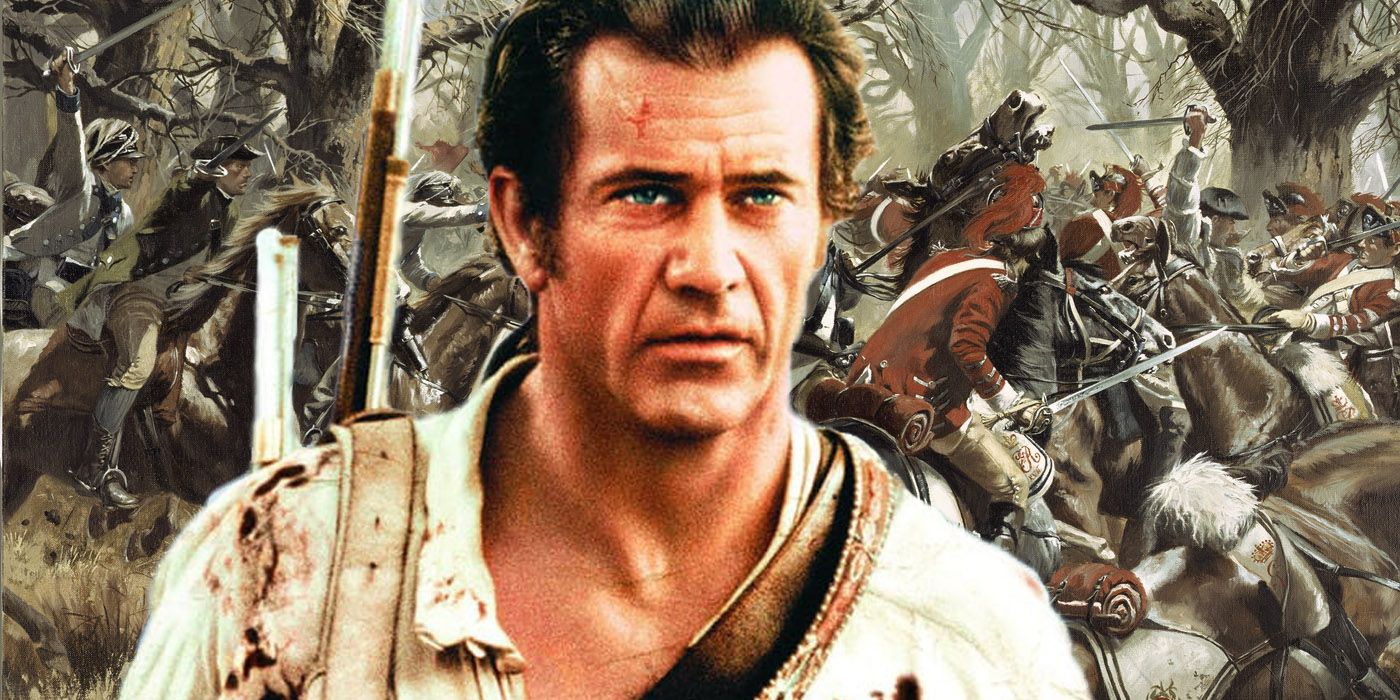

Roland Emmerich's 2000 historical war epic The Patriot, which stars Mel Gibson as an American revolutionary leader called Benjamin Martin, has become classic Independence Day viewing - but how much of what's shown in the movie happened in real life?

In The Patriot, Benjamin Martin is a veteran of the French and Indian War who is called upon to vote for South Carolina joining the American War of Independence. Martin is initially impartial, explaining that he believes in the cause but is not willing to fight in a war for it. Because he is not willing to fight himself, he is not willing to vote to send others to fight. However, his neutral stance comes crashing down when a group of Redcoats attack his home and their leader, Colonel William Tavington, murders one of his sons. Regretting his earlier inaction and determined to get revenge, Martin recruits a militia and leads them in a highly effective guerrilla campaign against the British forces in South Carolina.

The Patriot has been widely criticized for its unfair villainizing of the British, its invention of a war atrocity that didn't happen, and its sugarcoating of slavery. But while it may be more historical fiction than historical fact, the movie is partly based on true events and people. And when it comes to depicting the battle strategies used by both sides in the War of Independence, The Patriot demonstrates some impressive historical accuracy. Here's a breakdown of what parts of the Mel Gibson movie really happened, and what parts definitely didn't happen.

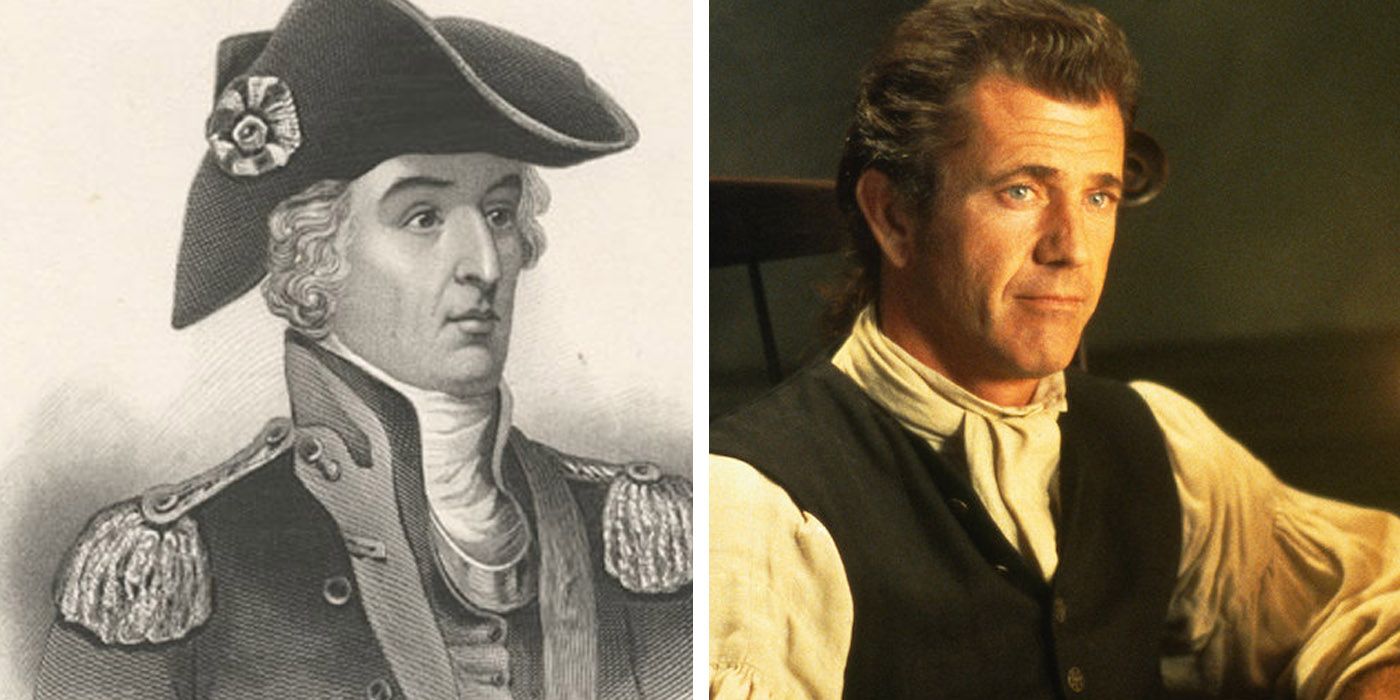

Benjamin Martin Is Mainly Based on Francis "Swamp Fox" Marion

There was no Patriot militia leader called Benjamin Martin who fought in the Revolutionary War, and the details of Benjamin's life and family are fictionalized. However, in the DVD featurette "True Patriots," screenwriter Robert Rodat explains that Benjamin is based on several different real historical figures: Francis "Swamp Fox" Marion, Thomas Sumter, Nathanael Greene, Andrew Pickens and Daniel Morgan. Francis Marion appears to have been the primary influence, since many details of Benjamin's character - including his role in the French and Indian War, his use of guerrilla warfare tactics, his gathering and leadership of militiamen, and his use of ambushes to gather intelligence - are lifted straight from Marion's biography.

Creating a fictional character rather than using any one historical figure gives The Patriot an excuse to leave out details that would have been harder for modern audiences to tolerate in a supposed hero. For example, the African-American characters who work in Benjamin's home and fields are said to be freed slaves who are devastated when they're forcibly taken away to fight for the British. Francis Marion, however, was a slaveowner who had a reputation for raping his female slaves, and during the war he targeted and executed freed slaves who were suspected of working with the British. He was also known for his persecution and slaughter of Cherokee Indians, which in the movie is rewritten as a single wartime incident that Benjamin Martin considers his greatest shame and regret. An anonymous source from Sony Pictures told The Guardian that the movie was originally supposed to be a factual biography of Marion, but "They couldn't go ahead once historians had given them chapter and verse on the Swamp Fox, so they had to change his name."

William Tavington Is Loosely Based On Banastre Tarleton

The Patriot's main villain is the cartoonishly evil William Tavington, played by Jason Isaacs, who is based on the real British soldier and politician Sir Banastre Tarleton. The real Tarleton led British forces at the Battle of Cowpens (the focus of The Patriot's third act), and was charged with the task of rooting out and capturing the "Swamp Fox" when Marion proved troublesome to British forces in South Carolina. Like Tavington in the movie, he was unsuccessful. Tarleton was given the nickname "the Butcher," but it wasn't because of a pattern of brutal treatment of civilians.

The nickname stemmed from a single battle, the Battle of Waxhaws, during which Tarleton was shot down from his horse and trapped underneath it. While he was unable to give orders, his temporarily leaderless men continued to kill Continental soldiers, many of whom were surrendering or not resisting. The Continental Army used the "Waxhaws massacre" in a propaganda campaign against the British, with a focus on Tarleton as the villain of the story. The campaign was very successful, and "Tarleton's Quarter" caught on as a saying that meant taking no prisoners. However, Tarleton was not the child-murdering monster that William Tavington is portrayed as in The Patriot, and Tavington's most monstrous act definitely never happened.

The British Did Not Burn A Church Full Of Civilians

Easily the most controversial scene in The Patriot is when Tavington corners a group of townspeople - including women and children - who have gathered to pray in church, and orders his men to padlock the doors and burn the church down with them inside it. While there were civilian casualties and buildings burned in the Revolutionary War, there is no record of anything like this being committed by either side. The Patriot has been heavily criticized for this scene, both because it misleadingly villainizes the British army and because it cheapens the horror of a similar real-life atrocity.

A version of this church-burning was committed almost 200 years later by an SS Panzer Divison during World War II, when the villagers of Oradour-sur-Glane in Nazi-occupied France were rounded up and massacred. At one point people were herded into the local church and grenades were then thrown in after them, with machine gun fire used to cut down anyone trying to escape through the windows. The victims included 247 women, 205 children and three priests.

The Patriot Heavily Sugarcoats Slavery

The other main area where The Patriot's historical inaccuracy is considered particularly egregious is its sugarcoating of how slaves and freed slaves were treated by the Continental Army in general, and Francis Marion specifically. The black characters in The Patriot are portrayed as freed men and women who earn a living by working Benjamin Martin's land, and who love his family and are treated like family themselves. As mentioned earlier, this was definitely not the reality for Francis Marion's slaves.

Both the British and the American armies tried to motivate slaves to fight on their behalf by offering them their freedom and even some payment after a period of service, and many slaves fled to fight for the British against their former owners. In The Patriot, however, the Martin family's freed slaves being rounded up to fight for the British is treated as a sad moment, whereas Occam being donated to Benjamin Martin's militia by his owner and earning his freedom through service is framed as a triumphant storyline. Director Spike Lee was particularly vocal about his disgust at how The Patriot "dodged around, skirted about or completely ignored slavery," calling it "pure, blatant American Hollywood propaganda. A complete whitewashing of history."

The Patriot Is Most Historically Accurate In Its Battle Scenes

Ironically, the aspect of The Patriot that might seem the most ridiculous is actually where it shines the most in terms of historical accuracy. The film portrays two key battles of the Revolutionary War: the Battle of Camden (which Gabriel and Benjamin observe from a distance) and the Battle of Cowpens (the final battle of the movie). The sight of the American and British forces stiffly marching towards each other across a field and then standing still and fully exposed in regimented columns while firing their rifles may seem strange compared to more modern tactics of trench warfare and defensive fighting positions. However, at the time firearms took a long time to reload (at best, a soldier could fire around three shots per minute) and were not particularly accurate even when aimed perfectly (the scene of Benjamin and his two sons sniping Redcoats with pinpoint precision is very unrealistic).

This meant that the key to victory in open battle was holding formation and firing as quickly as possible, because in formation soldiers became greater than the sum of their parts. Forty men standing in formation and firing in the same general direction would land more shots than those same forty men scattered across the battlefield and trying to aim at specific targets. And while one line of soldiers dropped down to reload, the line standing behind them could take aim and fire the next volley of shots. Victory could also be won by forcing the opposing side to break their own formation, which in the Battle of Camden was achieved through a bayonet charge that the American forces were unprepared for, and which caused them to panic and scatter.

The American soldiers at the Battle of Cowpens were led by General Daniel Morgan, one of the men that Benjamin Martin is based on, and the scene in which militia members are asked to fire only two shots and then feign a retreat really did happen. The plan was designed to draw the British forces forward, believing they had the Americans on the run, only to lead them into a prepared volley of musket fire immediately followed by a bayonet charge. The actual deaths and injuries inflicted by this surprise attack were arguably less important than the emotional shock of it, which broke the already strained morale of the British soldiers and caused many of them to flee, surrender, or simply collapse to the ground. While The Patriot's actual story may be largely fictionalized, the movie does a great job of showing the effectiveness of both line formations and guerrilla tactics during the Revolutionary War.