The film noir is one of the oldest and most well-worn staples of Hollywood cinema. Its tropes are so predictable and its worldview is so outdated that even the postmodern deconstructions of the genre are now over half a century old. The “neo-noir” has taken the already-ambiguous morals of the noir to even darker, grittier places.

The Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men is a traditional noir in its story of the blood-soaked search for a crucial MacGuffin, but it takes place in a sobering reality that robs viewers of the comfort of closure.

No Country For Old Men (2007)

Faithfully adapted from the unrelenting bleakness of Cormac McCarthy’s novel of the same name, the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men follows the hunt for a Vietnam veteran who stole a briefcase full of cash from the site of a drug deal gone wrong. Javier Bardem’s Oscar-winning turn as hitman Anton Chigurh made for one of the most chilling movie villains of all time.

With its briefcase MacGuffin and morally ambiguous characters, No Country is a classic noir. But its refusal to conform to Hollywood traditions like three-act storytelling and dramatic closure make it more of a haunting deconstruction of the familiar framework.

Pulp Fiction (1994)

After a groundbreaking, hugely celebrated debut movie like Reservoir Dogs, filmmakers are under immense pressure to follow it up with something even bigger and bolder. Quentin Tarantino more than delivered with the zeitgeist-grabbing postmodern antics of Pulp Fiction.

With his sophomore feature, Tarantino set out to tell the most familiar hard-boiled crime stories found in classic noirs – a boxer is bribed to throw a fight, a gangster takes out the boss’ wife, etc. – while putting a unique twist on them, like incorporating an unexpected drug overdose or trapping the characters in a pawn shop basement.

Drive (2011)

Nicolas Winding Refn brought the neon-soaked landscapes of Los Angeles to life in his critically acclaimed neo-noir thriller Drive. Ryan Gosling showcased a previously unseen dark side in the role of brooding antihero “The Driver,” a getaway driver who finds himself targeted by a ruthless crime boss after a heist gone wrong.

The sun-drenched streets of L.A. and the illicit work of getaway drivers had been seen in countless noirs before Refn transplanted those genre conventions into a modern setting with an engaging atmosphere and sparse but uncompromising violence.

Taxi Driver (1976)

Martin Scorsese has made so many incredible movies throughout his career that it’s difficult to name just one as the director’s magnum opus. But one of the strongest contenders for that title is 1976’s Taxi Driver, a New Hollywood take on the vigilante thriller that stars Robert De Niro as a lonely cabbie who decides to take the law into his own hands.

Tackling a poignant social issue of its time – the PTSD suffered by veterans returning from Vietnam – Taxi Driver is a quintessential neo-noir. With thick steam billowing out of sewer grates and trash piling up on the streets, Taxi Driver’s portrayal of New York’s seedy underbelly leans even more into the themes of urban decay than any noir from the genre’s heyday.

Point Blank (1967)

The delightfully simplistic storytelling of John Boorman’s Point Blank has made it one of the most effective and influential thrillers of all time. Lee Marvin stars as a gangster who quietly tracks down the business partners who double-crossed him and left him to die, leaving a trail of bodies in his wake.

One of the earliest deconstructions of the noir, Point Blank transplants a softly spoken revenge-seeking spaghetti western antihero into a contemporary gangster movie.

Oldboy (2003)

Park Chan-wook’s brutal masterpiece Oldboy strips the film noir back to its rawest elements, telling the story of a wrongfully imprisoned man who’s mysteriously released from jail and given a cell phone and some money to help him track down the people responsible.

The lack of justice, harrowing final plot twist, and mind-bending themes of existentialism make Oldboy one of the most essential neo-noirs ever made. Plus, it has one of the greatest fight scenes of all time shot in a long unbroken take in a blood-drenched hallway.

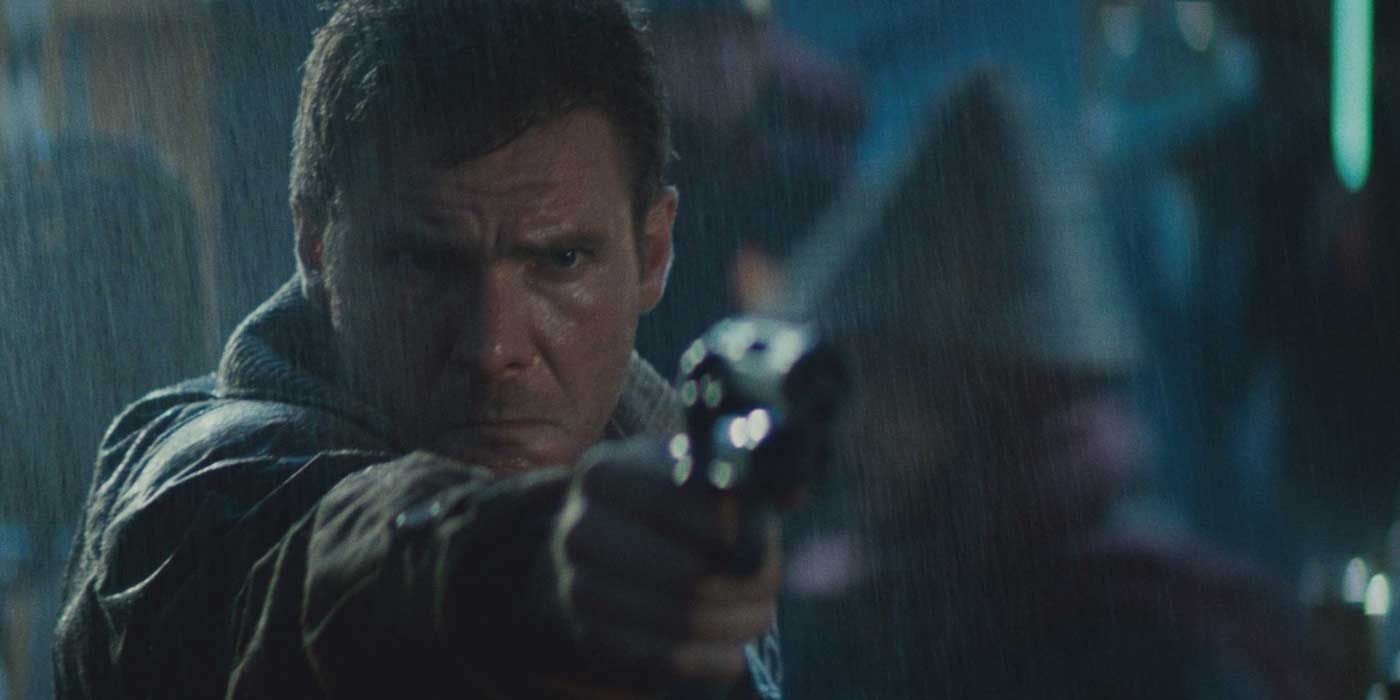

Blade Runner (1982)

Although it was initially overshadowed at the box office by E.T. and therefore overlooked by audiences, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner has since been re-evaluated as a timeless masterpiece. Harrison Ford stars as a “blade runner” in futuristic L.A. who’s tasked with tracking down various rogue A.I.s that have seamlessly assimilated themselves into human society.

Scott’s movie is notable for being the first to transfer the familiar conventions of film noir into a sci-fi setting. The femme fatale is an android, the hard-boiled antihero is unsure if he’s really human, and the Bradbury Building is reduced to a decrepit relic.

Blue Velvet (1986)

David Lynch’s movies have always reflected the tropes of film noir, from the gritty urban landscapes of Eraserhead to the exposure of Hollywood’s dark side in Mulholland Drive. Lynch’s uniquely surreal take on noir reached its peak with his disturbing masterpiece Blue Velvet in 1986.

The story concerns an everyman whose discovery of a severed ear draws him into a seedy suburban underworld where he falls for a sex worker and butts heads with her sadistic pimp, Frank Booth. The moral line is blurred when the hero begins to spot some of Frank’s uglier personality traits in his own behavior, sending him on a spiral of self-loathing.

Breathless (1960)

Widely recognized as the movie that kicked off the French New Wave movement, Jean-Luc Godard’s directorial debut Breathless offers a loose, experimental take on a classic American crime movie set in Paris. It’s an homage to classic noirs, but also a self-aware deconstruction of them.

The lead character isn’t a Bogart antihero; he’s a huge Bogart fan who wants to be a Bogart antihero. Godard’s chopping cutting robs Michel of the glorious cinematic moment he wants when he impulsively kills a police officer and flees the scene. Just when cinema was becoming rigid and stale, Godard’s stylistic flourishes came along to shake things up.