Many movies use creative ways to break the fourth wall between audience and narrative, with Daniels' recent hit for A24, Everything Everywhere All At Once, being an exemplary example. Fourth wall breaking doesn't have to be direct - involving a character looking directly through the camera lens, for instance - but when it happens in movies it is a metaphysical shock to the system, and if done well can make for an unforgettable scene.

Several classic movies have optioned to take the fourth-wall-breaking trope and channel it throughout their narratives, while others leave the technique until the movie's final shot, and the reasons for this can often vary according to what the director may be attempting to convey.

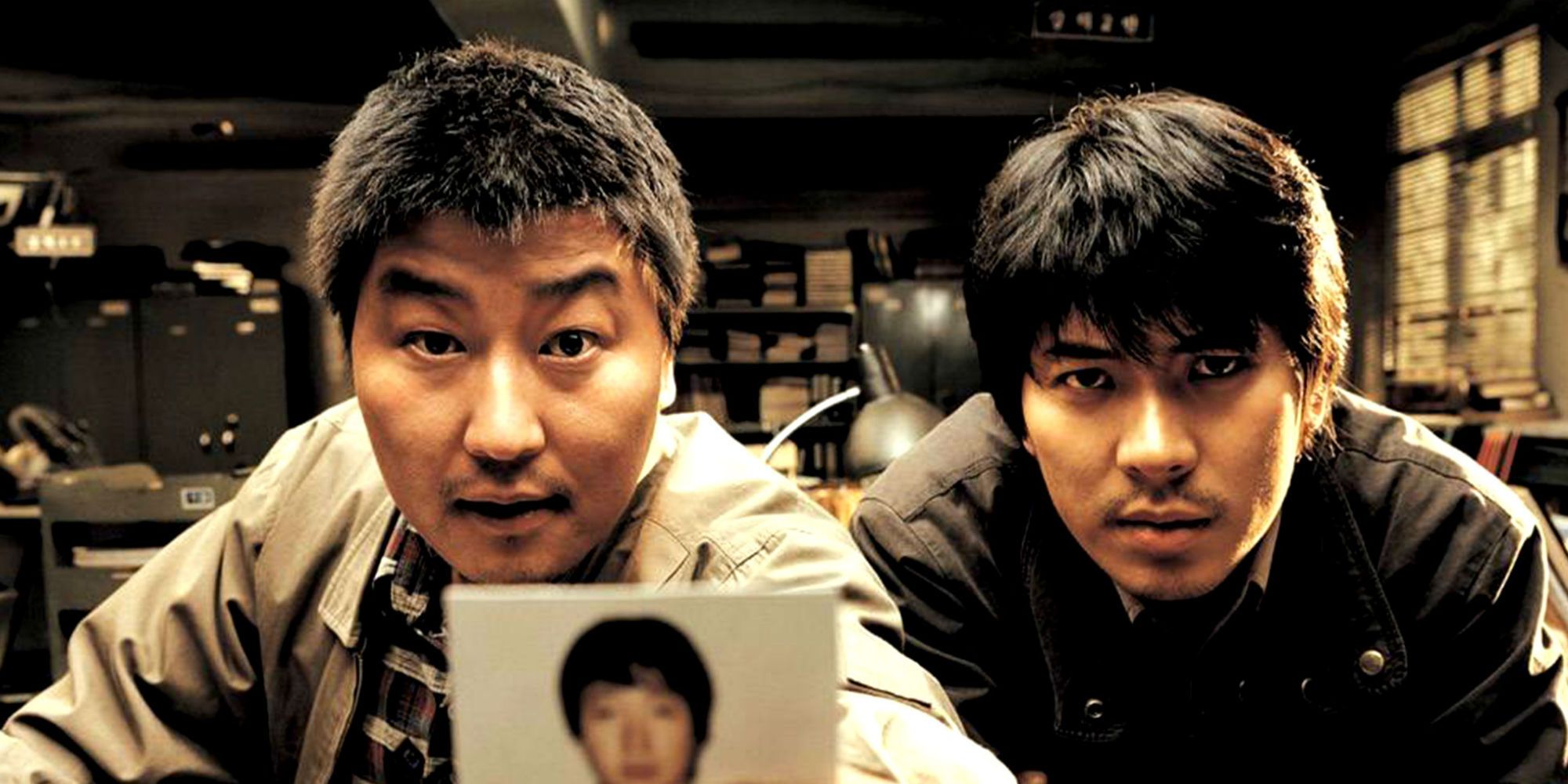

Memories Of Murder (2003)

Before director Bong Joon-ho rose to internationally renowned status with his Academy Award-winning Parasite, the distinctive auteur made the quasi-fictional-true-crime thriller Memories Of Murder, which was loosely based on a real-life serial killer case that became notorious in Korea and remained unsolved until very recently.

In the movie, the film's lead detectives become frustrated in their attempts to solve the mystery, and in its final shot, lead detective Park Doo-man looks directly into the camera lens as if to imply that somewhere outside the fixed realms of the movie's narrative, the true killer may be looking straight back at him.

Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986)

John Hughes' famous slacker comedy Ferris Bueller's Day Off is one of the most famous examples of a movie that has broken the fourth wall. Throughout the film, Ferris decides to talk directly to the camera as if to implicate the audience in his truancy.

In the final shot of the film, while Ferris is lying on his bed and looking into the camera, he delivers one of cinema's most famous lines: "life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you're gonna miss it." This parting salvo is a reminder to the audience that despite remaining complicit in Ferris' wild day, what they are watching remains fiction, and life still moves on outside the confines of the screen.

Psycho (1960)

Alfred Hitchock's seminal horror slasher movie Psycho is perhaps most famous for a certain scene set in a shower. The infamy of this particular scene often detracts from the movie's dynamic approach to storytelling, and Hitchock's film packs plenty of shocks throughout its narrative.

By the film's conclusion, the maniacal killer Norman Bates has been detained and is left in a prison cell to contemplate his crimes. His mind is possessed by the voice of his mother and he chillingly looks down the lens of the camera to remind Hitchock's audience that while the film may have concluded, evil is still everpresent.

This Is England (2006)

Shane Meadows' somber and heartbreaking coming-of-age tale This Is England shines an inquisitive lens on a transitionary period for youth culture in England in the early 1980s. The movie tells the story of outcast Shaun, who finds purpose in befriending a group of skinheads.

This Is England's climactic final act is a harrowing experience for both Shaun and Meadows' audience and after the young boy decides the break off ties with the movie's neo-fascist antagonist, he wanders to the beach, casts an English flag into the ocean, and looks directly into the camera. The final shot is almost positioned from the perspective of the director, who challenges his audience to stand up to the creeping fascist ideologies present in society today.

American Psycho (2000)

Mary Harron's adaptation of American Psycho from the famous Bret Easton Ellis novel of the same name plays with breaking the fourth wall throughout almost the entirety of the film's narrative. To whom, or what, Patrick Bateman is speaking is a hotly contested subject, but it nevertheless makes for a skin-crawling experience.

The movie's novelistic subject matter is written almost in diary format and this is perpetuated in the book's adaptation. It is unclear whether the terrifying Bateman is guilty of the crimes that are committed in the story, or whether they were just a figment of his deranged imagination. When the killer looks vacantly into the camera lens in the film's final shot he, in essence, asks the audience to judge him, and by proxy, to judge themselves accordingly.

Funny Games (2007)

Michael Haneke is the kind of avant-garde filmmaker who seemingly takes unbridled joy in playing with both the sensibilities of his audience and the structuralist concerns of narrative storytelling in general. The American-language shot-for-shot remake of his 1997 original Funny Games, was even playfully meta in its release date.

As the title indicates, what transpires in front of the audience's eyes in Funny Games is not, in the remotest way, a conventional horror film. Haneke plays with his audience's expectations and his malevolent antagonists constantly rework the film's narrative to frustrate viewers. In the movie's final shot Michael Pitt's Paul looks directly into the camera and smiles in a knowing way as if to suggest that the audience was the butt of all the movie's malicious jokes all along.

Enola Holmes (2020)

Millie Bobby Brown took a break from filming the hit-show Stranger Things by starring in a charming reworking of the classic Arthur Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes tale. Bobby Brown plays the titular Enola Holmes in the film, the younger sibling of the world-famous detective Sherlock.

The movie keeps its audience engaged with fast-paced storytelling, but also employs fourth-wall-breaking techniques to build a strong connection between protagonist and viewer. These techniques are continued until the movie's conclusion where Enola dissects the etymology of her name, which backward spells alone. It is clear from speaking to the camera that Enola had never been alone and neither had the movie's audience.

High Fidelity (2000)

By the time Stephen Frears' High Fidelity was released in 2000, fourth-wall-breaking techniques had been employed in countless comedies, to varying degrees of success. Frears' movie, though, certainly found an innovative way of engaging audiences with the narrative by breaking the fourth wall.

Throughout the movie, John Cusack's lead character Rob Gordon almost seeks advice from the movie's audience during his attempts at finding love. The audience plays a de-facto counselor for the film's beleaguered protagonist and it is redolent of the echo chamber dynamic singletons often share with their inner monologue thought-processes. In the film's final shot, Gordon once again interacts with the audience by breaking the fourth wall in a cathartic manner.

The 400 Blows (1959)

Francoise Truffaut's new-wave gem The 400 Blows was one of the most landmark examples of fourth-wall-breaking in filmmaking. The movie's tone is redolent of the delirium experienced by its youthful protagonist, who wanders the streets of Paris lost, hopeless, and alone.

In the film's final scene, Antoine runs to a beach and, without knowing where he is going, looks directly into the camera. The movie's narrative is semi-autobiographical and, by Antoine looking into the lens in the film's final shot, Truffaut is confronted by the boy he once was. The purpose that Antonie is searching for in the film, is therefore the film itself.

Goodfellas (1990)

Martin Scorcese is no stranger to employing fourth-wall-breaking techniques in his movies. Goodfellas is perhaps his most famous work that exhibits these tropes and its lead character Henry Hill talks to the audience throughout the movie's narrative.

Other than being a great way of breaking up the narrative, this technique is used by Scorcese to immerse the viewer completely with what is unfolding on screen. Since the movie is also based on true events, the audience is made to feel complicit in Hill's crimes, and in the film's final shot, Liotta's Hill looks into the camera before closing the door to his home behind him. This shot reminds the audience of the liminal boundary between cinema and reality.