As is often the case with elements of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, fully understanding Kamar-Taj (and, for that matter, a lot of the deeper lore as it relates to Doctor Strange) first requires a certain amount of background in cultural influences that inspired them. The comic book readership of the time was generally presumed to have been reading not only other comics, but also absorbing other popular fiction of the day. As such, lifting "big idea" concepts like Kamar-Taj from the broader pop-cultural ephemera was useful in part because readers could be expected to recognize the similarities to prior similar ideas and fill in the blanks themselves.

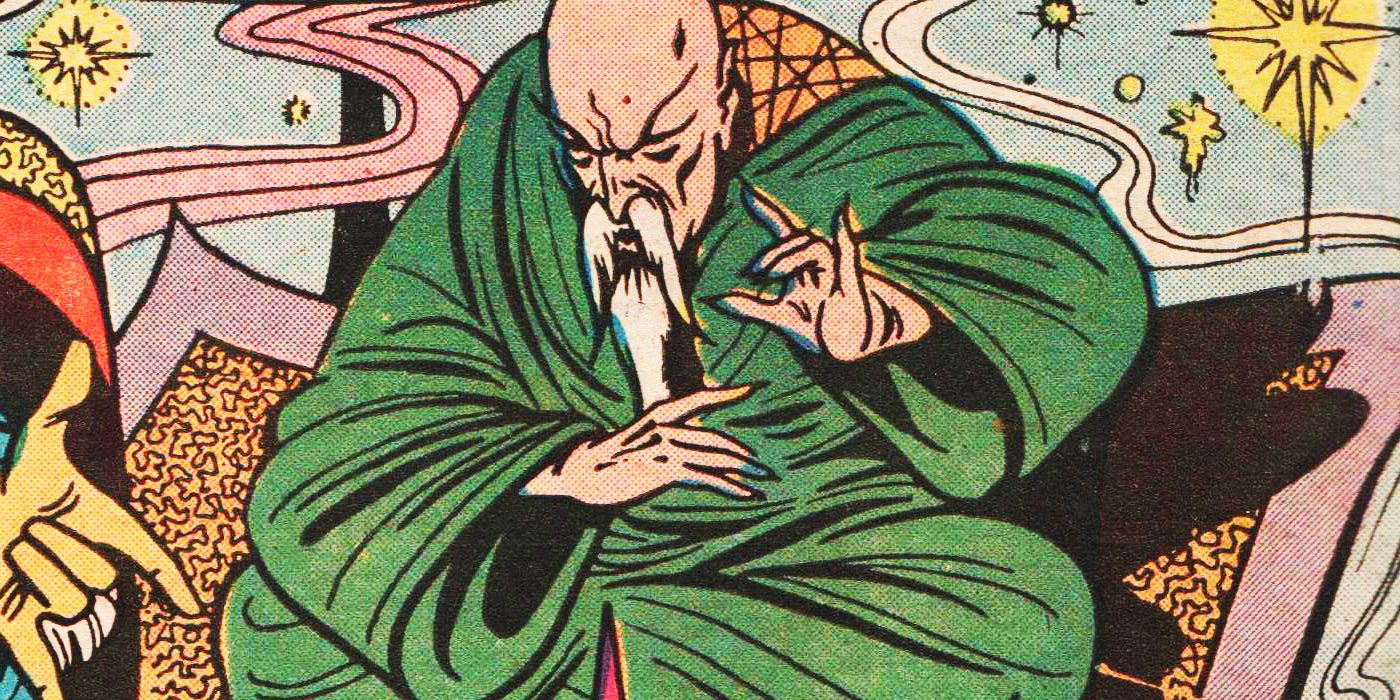

When it comes to the "mystic" side of the Marvel Universe, however, said understanding often demands a secondary level of engagement - one that's a lot less comfortable. Having been conceived largely in the mid-60s and early-1970s, Marvel Universe "mysticism" is grounded largely in the pan-Eastern spiritualism that was enjoying popularity in the U.S. at the time, and as such carries a lot of racially-insensitive connotations with the benefit of hindsight. Much like the rest of the culture, the creators of such material generally weren't acting out of malice - in fact, it's clear that a lot of the intent was to hold up "Asian culture" (here meaning a grab-bag of Buddhist/Taoist philosophy, meditative Yoga and martial-arts mythologizing) as a kind of superior ideal - but that intent is consistently hobbled by the same reductionist stereotypes of Eastern "culture" as the "Yellow Peril" villainizing that preceded it. In other words, the Ancient One wasn't really any more nuanced than the Mandarin; he was just a good guy instead of a bad guy.

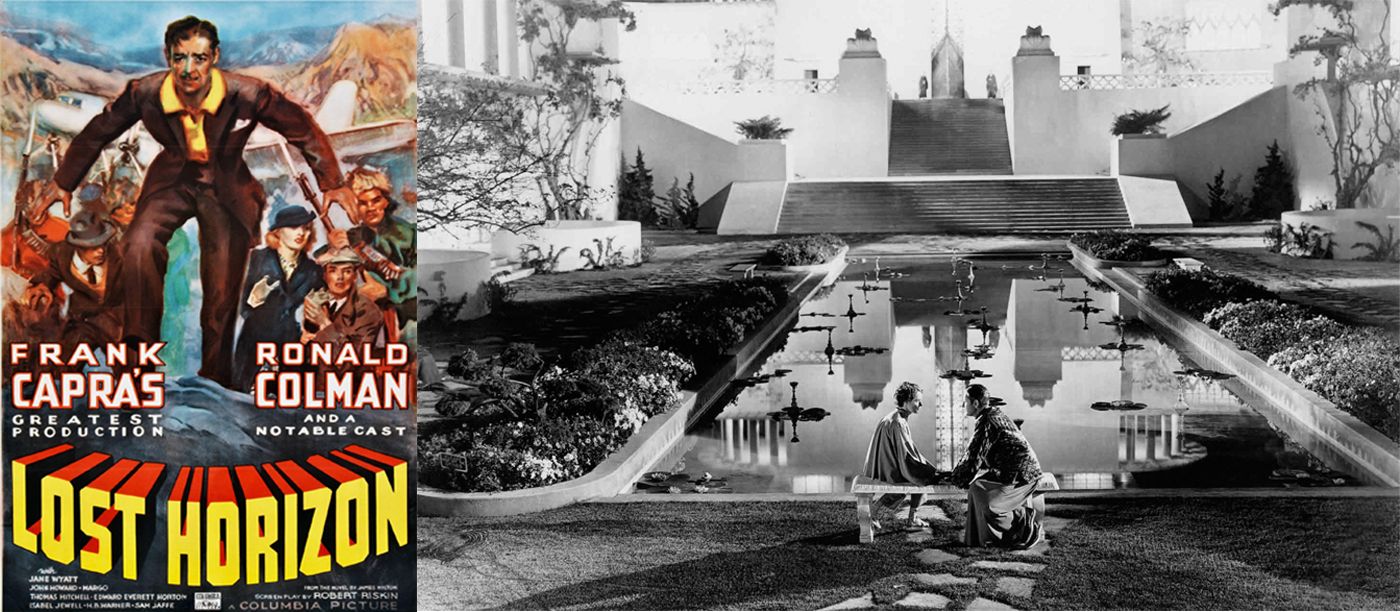

It's a thorny, troublesome tradition - and one that goes back quite far. Sometimes these superhero-mythology influences are vague and complicated. It's not clear, for example, whether Stan Lee or Jack Kirby were familiar with early "superhuman misfit" sci-fi stories like J.D. Beresford's The Hampdenshire Wonder, Olaf Stapledon's Odd John or A.E. Vogt's Slan when they conceived The X-Men. Other times, however, it's much more a case of simply giving a new name to a well-known story. Kamar-Taj - a mythical Tibetan city hidden in the Himalayan mountains where Doctor Strange receives his training as Sorcerer Supreme - is a rather textbook case of that second type, being a more-or-less direct lift of Shangri-La, the similarly mystical city at the center of James Hilton's classic novel Lost Horizon.

LOST & FOUND

Granted, just about every "lost city" story crafted since the 1933 publication of the book has drawn hefty influence from Lost Horizon and Shangri-La (there are at least 2-3 other places in the Marvel Universe with more or less the same inspiration, depending on how you look at it), but Kamar-Taj takes the cake in terms of sheer magnitude of things borrowed when it comes to its use in Doctor Strange's backstory vis-a-vis the conception of Stephen Strange as an "outsider" who becomes a champion.

In Lost Horizon, Hilton describes Shangri-La as a hidden village and lamasery located in the upper Himalayas where residents enjoy not only a utopian peaceful existence but unnaturally-prolonged, near-immortal lifespans dedicated to preserving a vanguard of human culture (implicitly, this is being undertaken should mankind once again imperil civilization itself with another World War.) The main story chronicles the exploits of a group of Western plane crash survivors who seek refuge in the hidden city, with specific focus on an English scholar named Conway who so endears himself to Shangri-La's High Lama that he is ultimately asked to become the Lama's apprentice and eventual successor... sound familiar?

Both Kamar-Taj and The Ancient One's sanctuary (they are not the same place is, which has confused even regular Marvel writers over the years, and it looks like the movie will elect to conflate them and simplify this considerably) are typically depicted very much in line with Hilton's descriptions of Shangri-La. That is to say, they belong to a highly-romanticized Western interpretation of self-sustaining pre-industrial Tibetan borderland communities popularized by National Geographic journalism and explorers like Joseph Rock - the botanist who "discovered" the autonomous Tibetan county of Muli in the 1920s. In both cases, the Western writers not only exaggerate the general functions of such communities, but also weave a mythic scenario whereby the location's isolation from the rest of the world is a chosen part of the residents' utopian lifestyle, rather than the other way around as in reality (i.e. surviving in an isolated location being possible only through communal interdependence).

This orientalist exoticism is, in both cases, troubling but also a bit on the quaint side; equally premised on the notion that these seemingly simpler places and peoples are actually so far advanced spiritually/philosophically that they don't even need modern Western conveniences. They also share an additional hook that the spiritual leaders of each respective place are charged with a higher duty around which the rest of the community has been entirely arranged. Preserving human higher-culture being Shangri-La's purpose, whereas Kamar-Taj, well... that's where it gets complicated.

ANCIENT HISTORY

Most of the backstory of Kamar-Taj was filled in retroactively over years of Doctor Strange comics, rather than being laid out at the start. Initially, it was simply a broadly-defined Shangri-La-esque place where Strange went to ask The Ancient One to heal his once-powerful surgeon's hands, and instead saved the old man's life and was invited to become Sorcerer Supreme instead. It wasn't until much later that Marvel began to offer background as to how the place came to be, exactly how ancient The Ancient One actually is and what it all has to do with vampires and Conan the Barbarian (no, really).

So goes the story: Many centuries ago, Kamar-Taj was an ordinary farming village and The Ancient One was a not-so-ancient child (there is some dispute over his given name) whose older friend Kaluu was endeavoring to learn various mystic arts and shared some of that knowledge with him - both becoming students of such practices and fast learners. What Kaluu did not share, however, was that some of the arts he'd begun to focus on were of the dark persuasion and had a corrupting influence - unsurprising, considering that he was introduced to them by the demonic Varnae, an eons-old refugee of Atlantis (the above-the-water version) also known as "Eldest of The True Vampires" and a semi-regular nemesis of Ghost Rider and Blade. And if that feels convoluted, wrap your head around the fact that Varnae and Darkhold both originate not in the pages of Doctor Strange, but in Marvel's licensed in-continuity comics based on Robert E. Howard's Conan the Barbarian, King Kull and Red Sonja stories - which are themselves a semi-canonical part of The Cthulhu Mythos (but that's a whole other article).

The two onetime best-buddies eventually come to disagree over what sort of place they should use their nigh-limitless powers to turn Kamar-Taj into once they finish using magic to eliminate disease and ageing from the populace. The Ancient One wants to create a sanctuary of magical study, while Kaluu would rather use mind control to raise an army and turn their tiny village into a world-conquering superpower. He almost pulls it off, too - but The Ancient One banishes him to the dark dimension of Raggador and vows to train harder and mold himself into a one-man bulwark against even greater inter-dimensional threats for the five-centuries it will eventually take Stephen Strange to come knocking. (Kaluu would subsequently escape, be pushed back by Strange, escape again, forego sorcery for the stock-market, and eventually help Strange defeat the Elder God Shuma-Gorath).

Five centuries is, of course, a lot of time even for a sorcerer - so after securing Kamar-Taj The Ancient One ends up traveling the world gathering up relics and other tools of the trade, effectively building himself a working museum of Magical Marvel MacGuffins. Maybe it's for the best that he decided not to keep stuff like The Book of Vishanti or The Eye of Agamotto there, and built a palace of his own instead.

THINGS TO COME

As noted previously, the Doctor Strange movie looks to have simplified the Ancient One/Kamar-Taj situation considerably. From the film's trailer, it seems as though the "lost city" is part of a fairly populous area (Chiwetel Ejiofor's Mordo even notes that it has password-protected Wi-Fi) - and it's possible that the name will here simply be ascribed to the temple/compound where The Ancient One conducts mystic-arts business. It's unclear how much, if any, of the place's comic origins as a Shangri-La-alike will make it into this modern reworking of the concept.

Maybe that's for the best. While Marvel fans (and comic/pulp fans in general) retain plenty of fondness for the kind of old-school adventure-fiction mythologizing that informed the original concept, the fact is an "authentic" Kamar-Taj would likely have only added to the already vast minefield of political, cultural and social issues that Marvel has had to navigate in order to bring Doctor Strange to the screen. With the Chinese government reputedly still willing to block the release of Western movies that ascribe too specifically to traditional Eastern spiritualism (or that are seen as overly-deferential to Tibet) and a variety of voices objecting to the casting of Tilda Swinton as a white female Ancient One, Disney would likely be relieved to not have to field questions about the problematic stereotypes and exoticism endemic to the original setup.

It does, however, raise the question of how Marvel plans to handle things when the problem comes up again. As mentioned, Kamar-Taj is only one of several Marvel Universe locales borrowing their foundations from Lost Horizon and Shangri-La. Iron Fist is currently in-development for Netflix, and features yet another Western interloper in Danny Rand becoming the favored son of yet another lost Himalayan utopia in the kung-fu fixated K'un-Lun. Will Doctor Strange's revisionism provide a window into how all such stories are handled? That may well depend on how audiences end up receiving what is already being called the most unusual Marvel Cinematic Universe movie yet.

Doctor Strange opens November 4, 2016; Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 – May 5, 2017; Spider-Man: Homecoming– July 7, 2017; Thor: Ragnarok – November 3, 2017; Black Panther – February 16, 2018; Avengers: Infinity War – May 4, 2018; Ant-Man and the Wasp – July 6, 2018; Captain Marvel– March 8, 2019; Untitled Avengers – May 3, 2019; and as-yet untitled Marvel movies on July 12, 2019, and on May 1, July 10, and November 6 in 2020.