[This is a review of Mad Men season 7, episode 14. There will be SPOILERS.]

-

The apparent degree of difficulty facing Mad Men, as it set out to complete its seven-year journey was, in many ways, directly proportional to the degree of difficulty facing Don Draper, as he set out to unburden himself of his worldly possessions and all the trappings that came from the life he had led since returning from war literally a new man. But that daunting task didn't keep the series, or series creator Matthew Weiner from delivering a profound, beautiful, and yet fittingly cynical ending to one of the greatest television series in the history of the medium.

Don Draper ends the series like he did the penultimate episode: with a contented smile. It is a smile that suggests he has finally had a genuine moment in his life thanks, strangely enough, to the transcendental experience of a self-help retreat in California (which, given the series' emphasis on the Golden State as a place rebirth and renewal isn't so odd). As the camera slowly zooms in, a look of peace emerges on Don's face. Then the scene shifts, and the series' final images and sounds become what is possibly the most famous Coca-Cola advertisement ever. The series ends with 'I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke'.

The implication here is that the famous ad is the brainchild of Don Draper. Weiner makes the wise decision to avoid directly confirming this, granting the finale the appropriate amount of ambiguity with which to leave audiences thinking and guessing. But the direct cut from Don's contented face to an ad filled with performers who bear a striking resemblance to the employees of the self-help retreat where he found his inner peace doesn't require too much in the way of clarification.

And yet a sense of ambiguity still resonates. Not necessarily due to the question of whether or not we're supposed to assume the ad was written by Don, but because of what it all means. This is, for all intents and purposes, an unexpectedly happy ending. A man who has spent his life running away from everything – his past, his name, his wives, his children, and finally his career – finds a place to be comfortable, stationary, and at peace; Don Draper has achieved that sublime experience he was on the verge of in 'The Summer Man'. The Coke ad, however, suggests a backslide wherein his understanding of a powerful moment is reduced to a television ad selling a sugary soft drink by means of inviting people to be a part of manufactured harmony.

The implication is that if you run far enough, you'll end up right where you began. It is perhaps the most tonally appropriate ending to a television series in recent memory. The more I think about it, the more I believe 'Person to Person' came as close to being the perfect ending of Mad Men that there could possibly be. That doesn’t mean the episode isn't perplexing at times, but like most episodes of the series, it becomes deeper and more enjoyable upon closer inspection.

Don spends almost the entire episode doing what he's been doing for the past few weeks: running away. 'Person to Person' begins with him streaking across the Bonneville Salt Flats, as if setting the land speed record would somehow keep the appropriate distance between him and all that he was attempting to leave behind. Not long after, and for the rest of the episode, Don finds himself at the aforementioned spiritual retreat with his sort-of niece Stephanie, where he seemingly finds what he was looking for the entire series: renewal and rebirth. It is a refuge, a sanctuary from the life outside world. And yet the dual connotation of the word "retreat" looms large the entire time.

Interestingly enough, despite underlining Don's propensity for running away, and all the allusions to the word "retreat", the episode is ultimately about making emotional connections over long distances. The person-to-person in the title refers to the calls Don makes to Betty, Sally, and Peggy. Each call sparks something different in Don and Jon Hamm's performance manages to convey the emotional weight of what he discovers during each conversation with a powerful kind of clarity.

The discovery of Betty's terminal diagnosis leads to Don insisting he take a role in Bobby and Gene's life, but Betty doesn't want the last months of her life spent arguing about where the boys will grow up and with whom. The move ostensibly transforms Don's journey out west into a kind of exile. The altered context of his setting sends him into a tailspin, wherein he realizes (and confesses to Peggy) he's done nothing with the name he's stolen. Worse yet, there is a second realization that the world he left behind has continued on just fine without him.

Don tells Sally certain decisions need to be made by grown ups, but he's not there to see his daughter make the decision to become the parent Bobby and Gene will soon need. He's not there to see Joan start her own production company, or Roger finally settle down with a woman of the appropriate age, or to see Pete and Peggy have a grown up conversation and come to understand their connection with one another and their places in the world – even if it's just for the time being, because, this is Mad Men after all.

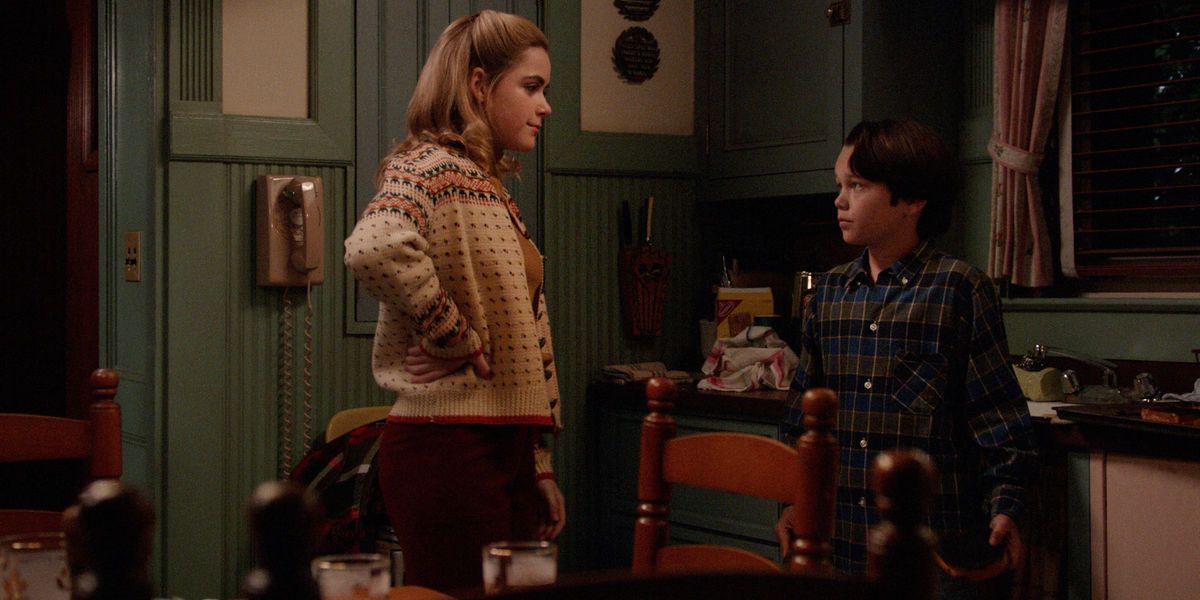

In the final hour of the series, Don is physically absent from these people's lives and the effect is like that of the Coke ad: it builds something affecting from the idea of a cumulative experience. Unlike the Coke ad, however, the emotion Weiner is able to create with a series of (mostly) happy endings feels genuine and earned, making the cynicism of showing the ad at the end all the more biting. Don's conversations with Sally, Betty, and Peggy require the viewer to understand and acknowledge the incredible series-long history between Don and the three women in his life. While Betty's ending is no doubt solemn, as she sits smoking at the kitchen table while Sally assumes her role, there's at least the sense that Betty has found some comfort in ending her life on her terms.

Meanwhile, in a wonderfully schmaltzy scene, Peggy realizes she loves Stan. This may be the one time Mad Men delivered a fan-service moment that was truly just that, but it's hard to complain about Peggy finding love when so much of her life is yet to come. Like Pete says, she'll probably be creative director one day. It's the kind of thing people say to one another before they part ways, but it still feels genuine. If we know anything about Peggy, it's that she's the one character no one (including Don) needs to worry about.

Because of the way the show is constructed, the way that it never relied on any one plot or genre convention to tell its story, the idea of a conclusion becomes something very different under the Mad Men banner. Contrary to what some might think about the nature of series finales, there really is no such thing as sticking the landing here. There's just the landing. It could be argued that the series already reached its natural conclusion in season 6, when Don opened up to his kids and revealed to them his childhood home. And if the idea of this story ending with a man standing with his children in front of a dilapidated house that once was a brothel doesn't suit you, you might consider the end of the first half of season 7 – and Bert Cooper's post-moon landing soft shoe rendition of 'The Best Things In Life Are Free' – to be the series' natural conclusion, making these past seven episodes something of a brilliant coda or denouement.

Either way it's fitting that what the show did was construct a narrative that felt deeply human and real, as it required the characters to experience different levels of change and then sought to illustrate that change in unique ways. It is like the sign hanging up in the McCann Erickson conference room: "The Truth Well Told". There is truth in Don welcoming his transformation in the series' final minutes, experiencing a genuine connection with a group of strangers. And there is truth to the idea that he seems to regress into the man he was before. Or is the truth that Don reinvented himself and became someone new? That's the other thing that's great about a show like this: You have to accept that the truth is just another story well told.