It's official: Daniel Craig is out as James Bond. That in and of itself isn't surprising, considering that Craig's most recent statements on the role involved speculating on which acts of self-harm he'd rather commit than play 007 again, and the lukewarm reviews for the underwhelming Spectre likely didn't help much. Now, Skyfall and Spectre director Sam Mendes has passed on further involvement as well; which means that Sony and Eon don't just need to find a new Bond - it's once again time to take the enduring franchise in a new direction.

What should be "new" about that direction, though, is anybody's guess.

The first step, in terms of reassuring the audience that (as the credits always tell us) "James Bond Will Return," is finding a new actor to take the role. Apart from the by now standard set of unlikely fandom-supported longshots, early word has centered on Tom Hiddleston, and were he indeed to take the role his wiry theatrical physicality and upscale affect would certainly be a change from Daniel Craig; whose brawny physique and neanderthal-brute-goes-to-finishing-school turn was the tip of the spear for the radical-reinvention that began with Casino Royale.

He'd also be by far the most famous (and box-office assured) a Bond has been before taking the role; having risen from unknown to instantly-recognizable household name as the most popular recurring villain of the Marvel Cinema Universe. In fact, a cynic could be forgiven for thinking that, perhaps, the producers pursuing Hiddleston in particular was indicative of a studio push for the next wave of Bond films to chase the Marvel aesthetic overall, though that might be reading a bit much into it - besides, "be more like the Marvel movies" is what every studio is telling the makers of their tentpoles.

One thing seems clear: Moving on from Craig would mean yet another new status quo for the series. The four prior films eschewed the previous mandate of keeping only loose continuity between installments, but it feels unlikely that the next film would attempt to continue the storyline with everyone pretending not to notice Daniel Craig having morphed into Loki - especially considering so much of Spectre's plot revolved around Craig's Bond heading into the autumn years of MI6 tenure. That means finding yet another fresh take on how Bond, a character increasingly removed from the world that spawned him, fits into modernity.

Or does it?

Every Bond film from the end of Roger Moore's tenure on has faced a similar problem: 007 was created at a very specific moment in time in service of a very specific vision - namely, a post-Imperial British power-fantasy of the old-school nobleman-warrior "Gentleman Spy" ideal having a vital post-WWII role to play in the "arms race" era of the early Cold War - and that moment had largely passed. Timothy Dalton's Bond tried to continue by acting as if the name and the tuxedo was all you needed (The Living Daylights and License to Kill are all but indistinguishable from other 1980s action features otherwise) while Pierce Brosnan's run was mostly content to coast by on irony - much to the consternation of its star. Craig's Bond walked an uneasy line between total reinvention and homage, with the most classically "Bond-like" installments (Quantum of Solace and Spectre) earning mixed reviews while the more radically-different Casino Royale and Skyfall were received much better; but the same theme has been running throughout: Bond doesn't fit into the world anymore.

Perhaps it's time to consider that this theme might be trying to tell us something?

Not every character is meant to exist outside of the context in which they were created. Robin Hood only really fits into a medieval world where the absence of kings and knights (all off fighting the Crusades) had created organized lawlessness. Dirty Harry only makes sense in a 1970s San Francisco where the social-upheaval of the '60s had curdled into something sinister. Captain America was so tied to World War II that Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had to make him, explicitly, a hero dragged into the future to revive him. Is it really so bizarre to consider that James Bond simply belongs in the milieu where he was conceived and popularized? And, if not, would it not be prudent for future Bond films to consider sending him back there? Not through "time travel," but by accepting that 007 simply "belongs" to the world of the swinging sixties and letting him be there: Making the next cycle of Bonds as period movies.

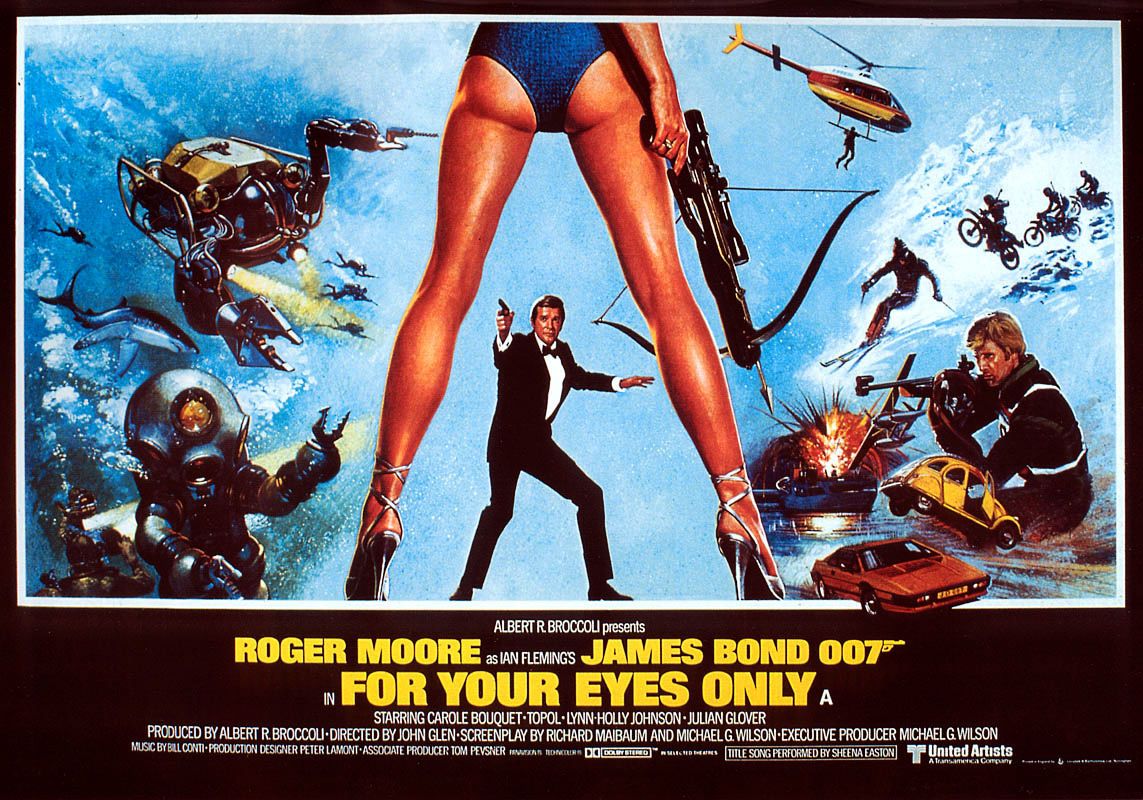

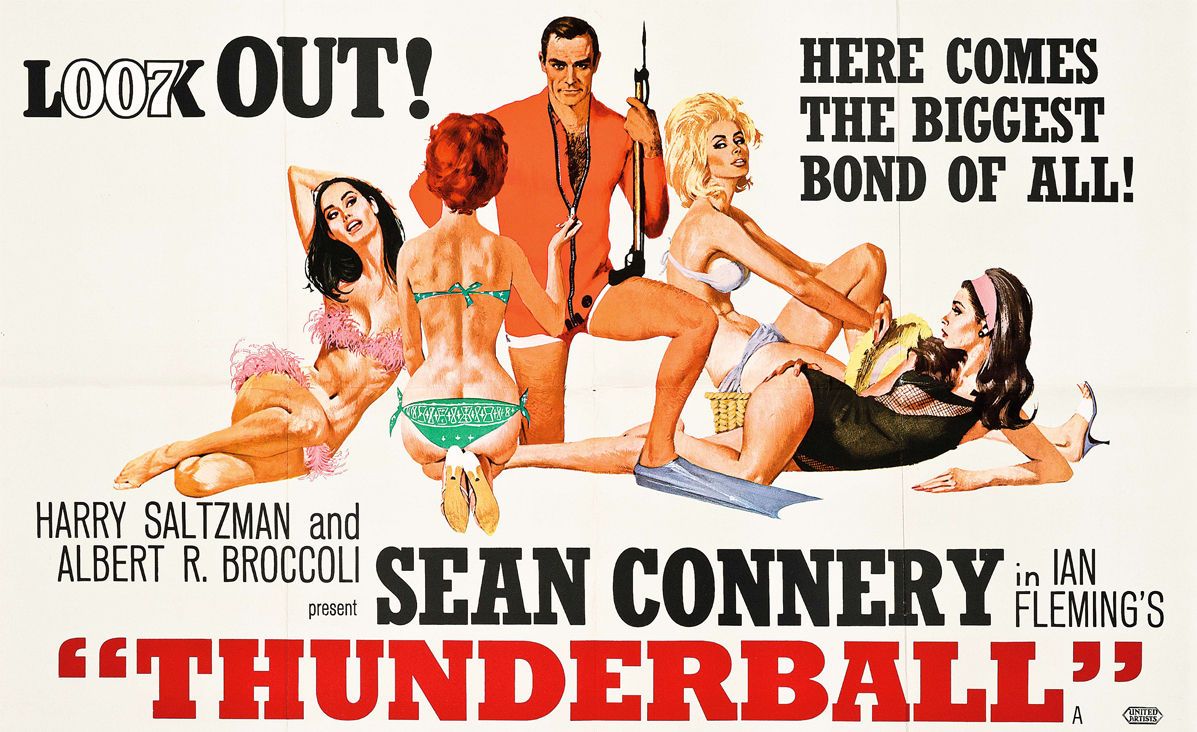

The immediate benefits would be that the franchise would once again be free to "lean into" its own aesthetic - even people who've never watched a James Bond movie, if asked to give the "bullet points" of one would likely return the same answers: Tuxedo, martini, gadgets, one-liners, henchmen with special-skills, "Bond Girls" with sexually-suggestive puns for names, elaborate supervillain plots and daring action setpieces; all of it kept light and peppy by a glib lounge-club sense of humor and set to blaring jazz-inflected orchestral music - and most of those elements have had to be downplayed (or worked in as ironic-homage) for the last few decades. A period setting would allow the "classic Bond" elements to take center stage once again, albeit with a touch of self-awareness.

Beyond Bond fandom, it would offer both audiences and filmmakers the lure of a unique aesthetic playground. Whereas the original films of the '60s mostly looked like a Hollywood version of then-reality, a film set in that world today would have the opportunity to take that level of stylistic flourish even further; creating the universe of a glamorous spy as it only ever existed in the ubiquitous kitsch postcards of the era - or the imagination of James Bond poster artists. Production designers would have free reign to play with the opulent decor of the sixties' exotica-loving upscale culture and to imagine the retro-futurist flair of both Bond's gadgetry and his enemy's lairs.

But that's only the surface business - the iconography. And if there's one thing the original Classic Bond era was good at teaching us, it's that just lining up the tropes in all the right places isn't enough to guarantee a good entry. Period setting or not, any new Bond will succeed or fail based not only on how well it tells its story, but how well it (re)establishes the necessity of Bond himself - i.e. "Why did this need to star the seventh guy to use this name, as opposed to Jason Bourne, or Captain America, or Ethan Hunt, or any of the dozens of other people who do this same basic job?" That second part, incidentally, has been where the post-Moore films have most often struggled to find their footing, but both questions are ably answered by heading back to when Bond works best.

The thing about James Bond is that he's not really as unusual as he now seems - or he wasn't meant to be. The series has endured so long beyond his origin that the aforementioned "bullet points" of his persona (overly-particular cocktail orders, conducting spy craft in expensive evening wear, bedding his enemy's female employees as a matter of course) have come to seem little more than a collection of quirks indistinguishable from the "wacky pets" and gimmicky food preferences of later action heroes; but once upon a time, everything about Bond made sense - sort of.

The typical outline of the quintessential 007 scenario (read: a villain's scheme can only be thwarted by an omnicompetent assassin who is also posh enough to infiltrate said villain's upscale, decadent social circle) is, yes, a contrivance. But in the days of the early Cold War (as fantasized by Ian Fleming) there was a logic to the so-called "Gentleman Spy". This was the beginning of the end of the moment in time when being (or seeming to be) an educated white man wealthy enough to afford a slick suit and order copious martinis was the camouflage necessary for slipping into any space important enough for matters of state to be happening.

Put more directly: Anyone can fire a gun or bug a phone, but not everyone can walk up to Auric Goldfinger on the golf course like they "belong there." And if you're thinking that all this makes James Bond sound like white male privilege, weaponized? That's because he kind of is - and should that mean the audience gets to vicariously enjoy his unfettered travel to exotic destinations, welcome access to beautiful, sexually-adventurous women, flashy cars, fancy parties, and blank check for collateral mayhem? Well, now you know why they keep making these movies.

Even still, the most enthusiastic proponent of turning the Bond features into period pieces for a cycle or two would have to concede that the argument so far approaches a self-justifying tautological loop: Of course James Bond movies would have an appealing, comfortable aesthetic as mid-1960s period pieces; the history of the franchise bears that out. Of course James Bond himself would be "easier" to write and/or flow more naturally as a character in the setting he was intended for; that tends to happen when there's less logistical heavy-lifting to do. Neither element, however positive in their own right, properly answers whether or not a temporal relocation would do anything worthwhile for the narrative. James Bond may look snazzier, fit more comfortably and play more enjoyably in the analog age, but what does it provide in the way of storytelling?

Simple: We already know what happens.

If there's one thing in the classic-era Bond films that doesn't hold up the way the fashion, style and energy does, it's the politics. That's not to say that 007 should be indulging in ham-fisted political message-mongering, but there's no getting around the fact that the more we know - even just through casual pop-culture osmosis - about what espionage and the history of power and policy in that era actually entailed, the more absurd and cartoonish Bond's adventures become. But that's only partially the fault of the films themselves, since their makers can hardly be faulted for not knowing what was "really" going on when whole government apparatuses were committed to making sure nobody knew such things.

But now we do know - as well as we're ever likely to - the beginning, middle and end of that particular story; and a period Bond adventure can only benefit from that perspective. The presence of megalomaniacal supervillains as 007's primary nemeses as opposed to "The Russians," for example, actually makes more sense in the context of hindsight. The Soviet Union was never as much of a global threat as it wanted to appear - its perception of economic and military might inflated via the mutual benefit that the myth of Soviet power gave to the machinations of both Moscow and Washington. In that context, Bond's existence actually becomes more vital: While the world is petrified by The Red Menace and "duck and cover" play-acting, this is the guy covertly putting down the "real" threats of S.P.E.C.T.R.E., Dr. No, Ernst Blofeld, etc.

There's also the potential urgency of placing Bond amidst real events in ways that may have seemed gauche in "real time". When JFK is assassinated in broad daylight under spectacularly suspicious circumstances, who would MI6's first "go look into this" call have been to? What was 007 getting up to during Vietnam? Was he keeping an eye on "subversive" countrymen like Lennon and Jagger? Where was he (or his enemies, for that matter) during the lead-up to "The Troubles" in Ireland? And these "big idea" dollops of depth are almost a garnish compared to the biggest narrative benefit to the period-in-hindsight approach: The ability to re-examine Bond himself.

The elephant in the room when dealing with James Bond as a character is that he is simply not a good person. "The Good Guy," certainly; that's what you get to call yourself when your actions prevent a mad scientist from nuking the planet. But as a human being he's reprehensible: A State-sponsored killer whose most relatable human trait is using the privileges afforded him in this profession to travel lavishly, live decadently and seduce scores of women under varying degrees of false pretense.

But while understanding this can make watching classic Bond films a cringe-inducing experience, trying to "work around" these traits can be downright tiresome. Yes, Connery half-strangling a woman with her own bikini top for information while the movie sees no issue with that is ugly, but Brosnan (or Craig) doing the - for lack of a better word - "politically correct" version of the same while the movie knowingly winks about it is boring and a bit cowardly about the core of its own fantasy. What would not be cowardly, though, is an authentically "ugly" Cold War Bond viewed from the benefit of hindsight. Call it the Mad Men approach: Don Draper was a fascinating anti-hero because of our awareness that his villainy was considered wholly normal - ideal, even - for his time.

A Bond pitched at that level - a "necessary evil" weapon of espionage whose callous violence, Mephistopholean sexuality and aptitude for both render him at once repulsive and yet perversely enviable - would be the most fascinatingly honest presentation of the archetype you could put onscreen. Could it be done in a modern setting? Sure, but the result could be entirely too dark to also be entertaining in the manner even a "serious" Bond demands, whereas a period setting affords the audience a suitable level of detached self-reassurance that things are better now - which is also the Mad Men approach. It's also a version of Bond that an actor like Hiddleston (who became a star by turning a genocidal fop like Loki Laufeyson into a hearthrob) could really sink his teeth into.

Is a period piece the only way to "rescue" James Bond? Probably not, but it's a way forward. Hollywood has spent 30+ years trying to change the way we look at each "new" idea of 007 - maybe it's time to acknowledge that a more interesting change would be the angle from which we look at the original.