Warning! Major SPOILERS for The Irishman ahead.

Martin Scorsese’s latest movie, The Irishman, is now on Netflix, telling a (mostly) true story about gangsters, deceit, and the perils of aging. After much hype and an endless amount of Marvel-adjacent discourse, the newest Martin Scorsese film made its debut on the streaming service.

The Irishman is a long-time passion project for Scorsese and star Robert De Niro, based on Charles Brandt's book I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank "The Irishman" Sheeran and Closing the Case on Jimmy Hoffa. Sheeran (played by De Niro) was a labor union official who had close ties to both the Bufalino crime family and Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa. While many elements of Sheeran's story have been disputed, his own claims to have not only been a mafia hitman but the man who killed Hoffa, whose body has never been found to this day, made him an irresistible subject for Scorsese.

The Irishman is ambitious, even by Scorsese's own lofty standards. At 209 minutes, it's easily the director's longest film and allegedly his most expensive too, with an official budget of $159 million (although some journalists assert that it was closer to $200 million.) The story covers decades of Sheeran's life and uses extensive CGI de-aging technology to take De Niro from his mid-20s to his early 80s. Gangster stories are nothing new for Scorsese - indeed, he may be the most iconic director of the genre still working today - but The Irishman takes him into a more melancholy and existential exploration of well-trodden material.

What Happens In The Irishman's Ending

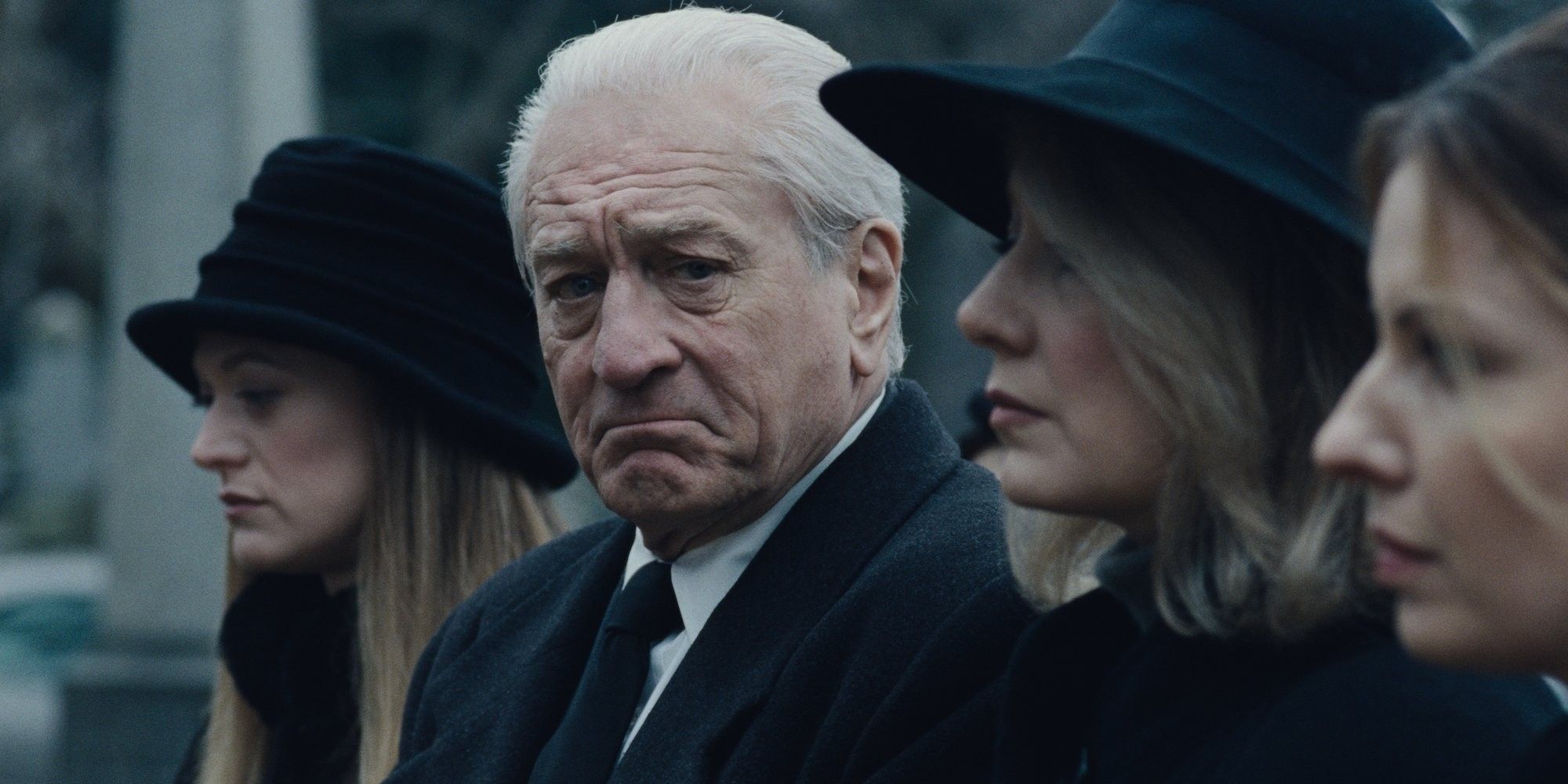

The Irishman opens in a mundane and somewhat damp-looking nursing home, where Frank Sheeran, incapacitated and sitting in his wheelchair, recounts his life's story to the audience. It's a savvy call-back to the iconic narration of Goodfellas, but this time, the establishing tone is far less cocky and victorious. The story unfolds with Sheeran's account of his life and alleged crimes, including his work with Jimmy Hoffa (played by Al Pacino) and Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci.) Over the course of many years, Hoffa and Sheeran become close not only as colleagues but friends and collaborators, with Hoffa forming an especially tight bond with Sheeran's daughter Peggy (played as an adult by Anna Paquin.) During this time, the battle for leadership of the Teamsters hots up and Hoffa faces tough opposition from colleagues as well as Robert F. Kennedy, the new Attorney General who launched a senate select committee on improper activities in labor organizing nicknamed the "Get Hoffa Squad."

Eventually, Hoffa is sent to jail for jury tampering but is released via a Presidential pardon from Richard Nixon in 1971, on the condition that he not participate in any Teamsters activities until 1980. Hoffa, of course, refused and began fighting to retake the top spot from his replacement, Frank Fitzsimmons, which led to fears from the Bufalinos that the crime families would not approve of his behavior. It falls upon Sheeran to "take care" of the problem. In 1975, as Sheeran and Bufalino are driving together with their wives to a wedding, Russell informs Frank that Hoffa's death has officially been sanctioned, and Frank is sent on a private jet to execute his duty. Due to their friendship and deep-seated connections with one another, Hoffa explicitly trusts Frank as he drives him to a new house where their supposed meeting with a local crime family figure has been scheduled. Upon entering the empty house, Hoffa realizes there's a set-up and turns to warn Frank. Sheeran shoots him at point-blank range, leaves the body to be disposed of by other gangsters, then flies back to the wedding.

Eventually, Sheeran and Bufalino, along with many of their collaborators, are jailed on various charges but never ones related to Hoffa's disappearance. One by one, they all die in prison, except for Frank, who is left old and alone with nothing to show for his life or the supposedly indelible mark he left on history.

Why Frank Sheeran Kills Jimmy Hoffa

For many of the younger generations, the name Jimmy Hoffa is probably one they are only aware of through cultural osmosis. It's easy to overlook just how intensely famous and powerful he was at his peak, especially now given the absolute diminishment of the labor rights and union movements in America. Hoffa was a lifelong union activist who secured the first national agreement for teamsters' rates in 1964 with the National Master Freight Agreement. Under his leadership, the Teamsters became the largest union by membership in the United States, with over 2.3 million members at its peak. Almost as well-known as his union-management was his involvement in organized crime. He faced major criminal investigations but avoided conviction for many years (his lawyer was Bill Bufalino, cousin of Russell, and is played in the film by Ray Romano) until Robert F. Kennedy decided to focus on him with his committees. Eventually, when Hoffa was charged with jury tampering and sentenced to eight years in prison, it came to light how he had improperly used the Teamsters' pension fund to give loans to leading organized crime figures.

Hoffa's disappearance has been one of the great unsolved crimes of the 20th century. It's a mystery mired in sleaze and speculation, and plenty of conspiracies over his ultimate fate have been formed over the decades. Sheeran's claims are but one of these answers to this eternal question. As shown in The Irishman, Hoffa's death was sanctioned by the Bufalinos because he knew too much. The two families were intertwined, with the Teamsters having hefty financial ties to the crime syndicate headed by Russell. During a testimonial dinner in Sheeran's honor, Russell tells Sheeran to confront Hoffa and let him know that the major crime families are unhappy with his attempts to get back in charge of the Teamsters. Hoffa does not listen and lets Sheeran know that all the dirt he has on the Bufalinos will ensure that he remains untouchable. Given how much money he loaned to the family over the years, it seems that he probably had some serious stuff in his favor. As many a Scorsese movie has shown, trying to get one up over the mafia almost never works.

Bufalino insists the hit is not personal, it's just in the best interests of his business, and since Frank is technically his employee and the man he sends out to do all his hits, this shouldn't be personal for him too. Of course, that makes little sense given that Bufalino deliberately helped architect the partnership between Sheeran and Hoffa that evolved into some sort of friendship. Hoffa trusts Sheeran in a way he probably doesn't do with anyone else he isn't directly related to, hence how his first move upon entering the empty house where he is to be killed is to check that Frank is okay. Ultimately, Frank Sheeran is the staff, the hired help with no true power in this messy ecosystem, and he does as he is told, just as he has for his entire life since joining hands with the Bufalino crime family. It's all too personal for Frank but he doesn't refuse the job, which is his biggest fault and what the movie drives home as the root of this sickness of violence that permeates Frank's world.

Why Peggy Can't Forgive Frank

The Irishman is a pretty testosterone-heavy movie that doesn’t have many major female roles. The biggest part goes to Anna Paquin as Peggy Sheeran, and as many critics have noted, she barely gets four or five lines of dialogue throughout it. Her stony silence and obvious fear and disdain for her father are a tough reminder of how Frank’s chosen life path has left him devoid of tangible and unconditional human connections to the rest of the world. Peggy’s closeness with Hoffa, a man she seemed to prefer over her own dad as a child, only further highlights the rift between father and daughter. When Hoffa’s disappearance is reported, Peggy seems to instantly know that her father had something to do with it, and following this, she decides to fully remove him from her life. Even when he tries to visit her at her job when he’s old and borderline infirm, she blanks him, refusing to give him even the dignity of a conversation.

In a narrative built mostly on the backstabbing machinations of male crime families and their intersections with union organizing, where everyone seems painfully aware that they’ll die prematurely from a bullet in the back of their head, it’s Peggy’s rejection of Frank that stings the most because his ignorance over his paternal duties in favor of being the Bufalino/Hoffa right-hand-man has left him alone in ways he was never prepared for. In retrospect, he should have known from the beginning how a life of violence would leave his family at arm’s length at all times. One of the reasons Peggy fears her father is because she has borne witness to his blood-stained fury from an early age, including an incident where he beat a shop worker into a pulp for grabbing her arm. Frank’s violence and secretive work were tough enough for Peggy to tolerate, but him having a hand in the death of Hoffa, a man she deeply admired and who she thought her father felt the same way about, was just too much for her to bear.

The Real Meaning Of The Irishman Movie

After the director made his comments about Marvel movies, many people shot back with an insistence that all of Scorsese’s films are derivative gangster movies. Aside from this being crudely inaccurate (this is the man who made movies about the Dalai Lama, the movies of Georges Méliès, and a musical starring Liza Minnelli), it was also grossly reductive of said gangster titles. What makes Scorsese so celebrated as a storyteller in this particular genre is his keen understanding of how even the most rose-tinted view of a life of crime cannot conceal its true demons and inevitably bad ending. Goodfellas gets accused of glorifying the mafia to this day, a point that seems to overlook how the film shows its lead descending into coke-fuelled paranoia and a life of isolation.

The Irishman shares many characteristics with films like Goodfellas and Casino and makes some clear call-backs that Scorsese fans will appreciate, but its true genius is in its overwhelming sadness. There is absolutely nothing about Sheeran’s life that is appealing or aspirational. Any glimmer of intrigue or allure that these men’s lives may have had in their youth quickly dissipates as they become old men. Their endless talking in codes become near-indecipherable, even to them, and the weight of their chosen lives crushes them every single day. There is no glory to this backstabbing or grasping for power, be it from Bufalino or Hoffa. Sheeran doesn’t even have any of this power. He’s been a goon for decades and remains one until the day he dies. He has never possessed any true autonomy and, almost like a dog, obediently does whatever Russell Bufalino tells him to, even if it means killing the one man who he could have called his best friend.

Much has been made about the film’s de-aging technology and whether or not using it was the right choice. While it does make De Niro and company look a little bit like Call of Duty cut-scene characters at time, and De Niro doesn’t help much by still acting like his 70-something self when he’s supposed to be in his 30s, it does serve a fascinating metatextual purpose. As much as Scorsese’s career has been defined by the gangster movie, it has been shaped by his long-time collaborations with Robert De Niro. In many ways, they have grown up together in the industry and become legends alongside one another. The Irishman is an often very literal take on that notion and one that acts as a fascinating commentary on both Scorsese and De Niro’s careers. This a movie first and foremost about old men coming to terms with their own mortality and the impact they’ll leave behind on the world that they have a complicated legacy with. Fortunately, Scorsese and De Niro's respective legacies are secured and will never fade away, no matter how many people sneer that their work in inaccurate terms.

Given the questionable veracity of Sheeran's claims, The Irishman cannot help but also be a film about the passage of time and perceptions of memory. Whether or not Frank Sheeran really did kill Jimmy Hoffa on the orders of the Bufalino crime family ultimately doesn’t matter because the life that Sheeran has insisted he has led has given him no satisfaction in life. It hasn’t made any of his associates happy either, and their increasingly cryptic conversations to one another signify both the smothering nature of a life lived in secret and how ultimately nobody even seems to know why they’re killing one another anymore, other than because it’s all they seem to know how to do. By the time they are sick old men in prison with nothing but one another for company, the loneliness of their existences is hammered home. Frank has nobody to tell his stories to other than disinterested nurses, a kindly but distant priest, and the unseen audience, and it just leaves him feeling more empty than before. Frank Sheeran comes to represent the end of an old way of life, one that the rest of the world seems happy to be without. The Irishman ends with the door left open on the past but one nobody wishes to return to.