Warning: Never Never is a MATURE Comic

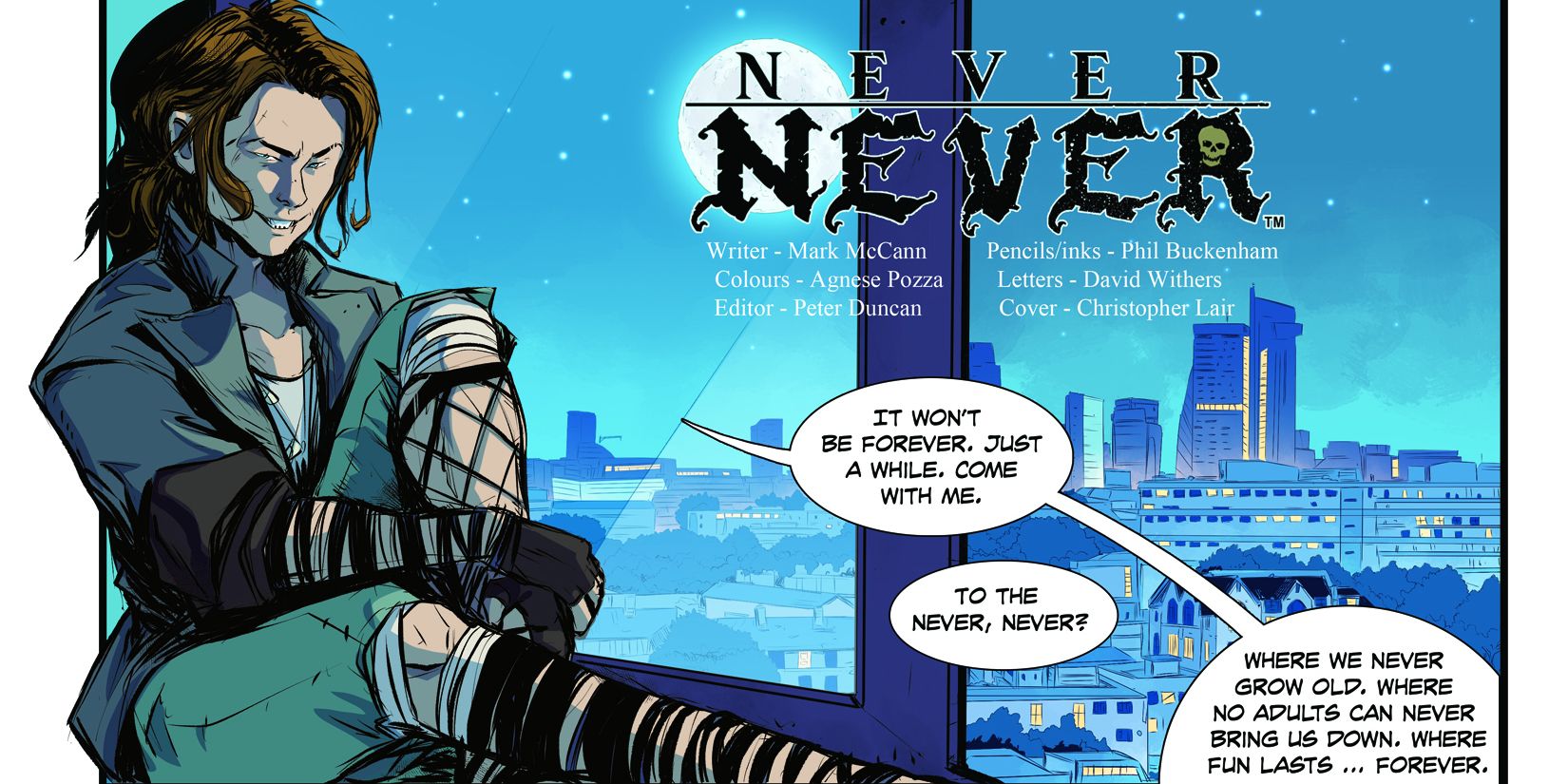

In today's mixed-up world, sometimes even our fantasies can get can away from us. So it is with writer Mark McCann's new survival horror/fantasy miniseries Never Never, a spin on the old J.M. Barrie stage-play which transforms the classic Peter Pan setting into a terrifying fever dream filled with violence and human sacrifice. Starring Winter, a young girl spirited away to the magical island of Never Never by a mischievous boy named Petros, the situation quickly devolves into an adrenaline-fueled fight for survival, as Winter is hunted by Petros and his deranged band of lost boys.

Tinged with elements as varied as The Hunger Games, Neflix's Mindhunter and Robert Kirkman's The Walking Dead, McCann is clearly aiming for the kind of mad action-packed gore-fest teeming with philosophical quandaries that his publisher Heavy Metal is known for, and this five-issue series from their creator imprint VIRUS hits the mark quite palpably, if a break-neck paced fight for survival amidst a magical isle is what you're looking for. Screen Rant caught up with McCann from his home in Belfast to talk Peter Pan, serial killers and the storytelling philosophy behind absurdist dark fantasy. Check out the interview with exclusive preview art below!

Screen Rant: I couldn’t help but notice that it draws a lot from the whimsical stage play by J.M. Barrie called Peter Pan except it’s kind of like that if that were like hell.

Mark McCann: I wouldn’t go as far as to say I’m a massive J.M. Barrie fan. I have enjoyed the material obviously enough that it’s left an impact on me, it’s left an imprint. But I remember enjoying Hook, and I enjoyed the various Peter Pan movies and the animated film, but it never really blew me away. Never Never was a concept where I thought, ‘what would that be like if it really existed?’ I ended up taking it to a dark conclusion where I thought ‘well, imagine you’ve got this island, and people are washing up there and it’s full of kids’. And what are kids like whenever they have no adults to look after them? J.M. Barrie writes them very… they like to frolic and get up to adventures and it’s all very playful. It’s got a sinister edge too, there’s always that sinister edge where Peter Pan had cut off Hook’s hand and fed to it a crocodile. So I always thought, well, there’s that cruel edge to childhood.

If you ever watch films like Lord of the Flies or read the book, childhood is, unless regulated, it’s a very cruel place. The bullies come primarily out of childhood. The damage that’s inflicted on you in childhood tends to follow you. It leads to your prime years for absorption of all that environment, psychologically you’re developing. And I thought ‘what happens when you take a bunch of disturbed children, and you put them on this island, and eventually, over time, the resources run out, and the only adults in they’re encountering are people who have washed up and don’t really know what they’re doing there- what happens? How does that interaction conclude?’

You’ve got these kids who’ve never been regulated, they’re borderline feral and then you’ve got these adults who are just sort of shocked to be there. And so I thought ‘this is gonna be war, and it’s gonna be horrible’. And you’ve got these kids who’re growing up- well they’re not even growing up… they’re brains are aging, they’re developing into older people but their bodies stay exactly the same because, in the environment of the island they don’t physically age, they can’t be aged and they can’t die. That was the natural dark conclusion that I came to.

And then I thought, ‘who runs the place? How do you keep everyone in line? Is there a deity, do they all believe in something? What happens when you throw a regular person into that mix?’ That’s where the survival horror element comes from. I thought that would be interesting.

SR: Survival horror…you’ve said in the press release you’re looking at George Romero and horror of that ilk. But, survival horror, that phrase in particular comes from videogames, specifically Resident Evil. Obviously videogames have been infiltrating their way into other media, literature included. Is that an influence on you?

Mark: Videogames? Yes. I’ll tell you what one of the biggest influences was with regards of I how I thought of this place. I don’t know if remember the rebooted Tomb Raider game. It’s Lara, she’s a novice, she’s trapped on this island and it’s a survival horror game, but it’s also got those tomb raiding elements, but I wanted to take this purely in the direction of horror, and sort of have more of an existential angle to it. But yeah, I think you’d be hard-pressed not to be influenced by games now, because games are so massive and expansive and they’ve got these wonderful narratives. I think it’s a matter of time really before we start to immerse ourselves in that in a very, very complex level with VR and things like that. But yeah, I mean, some of my favorite stories in recent years definitely come out of videogames. I love the medium, but also I love books, I love comics, I love film and TV. I love all the mediums that are there to tell stories, and I’ll definitely say that videogames- I hadn’t been a gamer in maybe about 10 years and I got a Playstation 4 one year, I just decided to give it a try. The games now are so complex, nuanced and interesting that it’s really an unbelievable medium for storytelling. So the short answer was, yeah, it’s hard to escape from the influence of games.

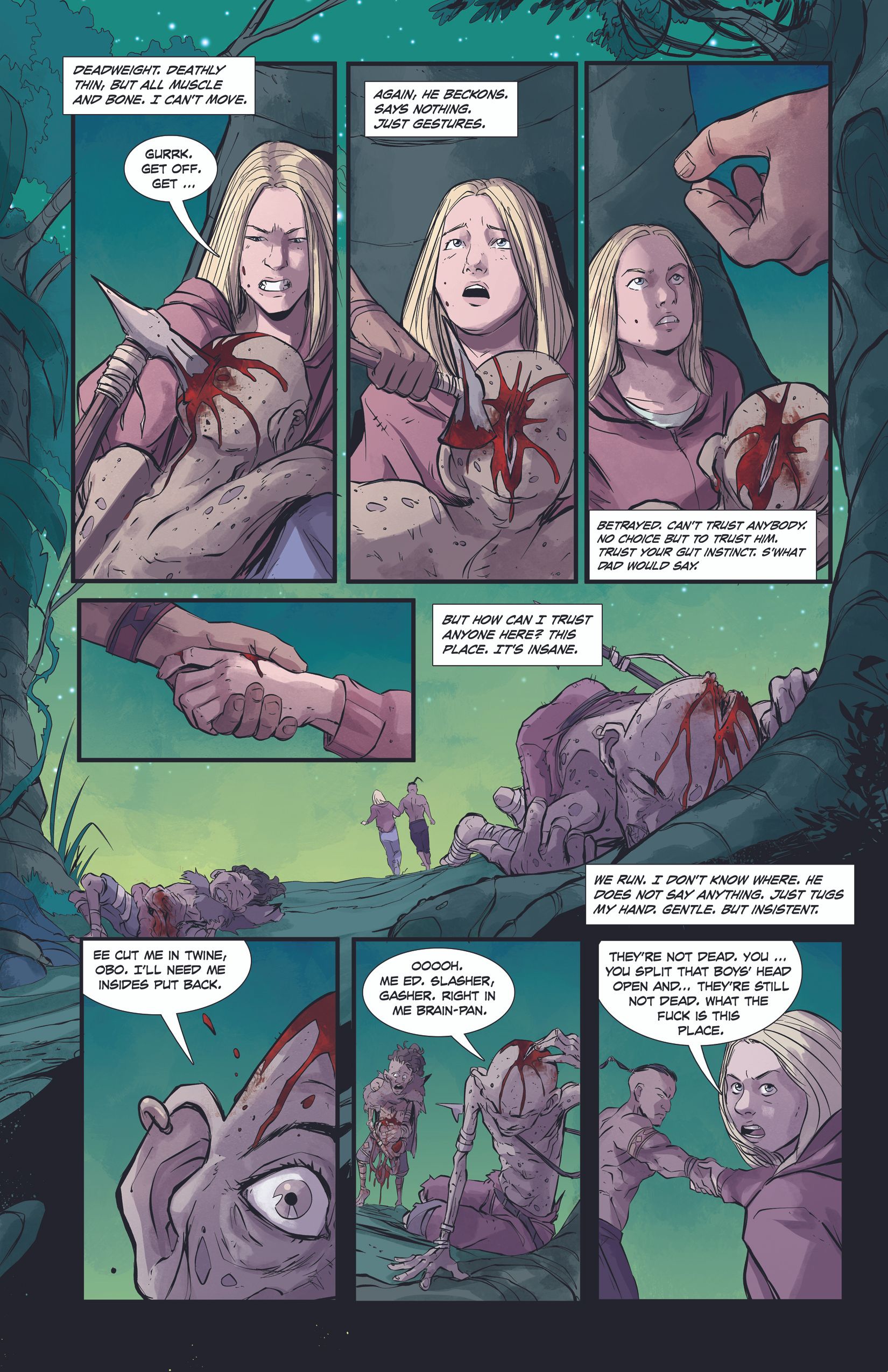

SR: Let’s talk about those lost boys you’ve cooked up. They’re these demonic, horrible monsters. They’re cannibals who regenerate.

Mark: One of my favorite movies I should say The Lost Boys, although again, I was very tacit whenever I spoke to people about pitching this around, I didn’t want to go down that direction because I think that movie was so fantastically done. It was a lot of really wonderful things that came together at the same time so it was a great script, Joe Schumacher, a lot of improv from an amazing cast, I love that movie. And I love the idea of a mortal- what do you do if you’re a mortal and you’re stuck in that body? It plays into what these boys on the island that I’m writing about [are going through], they’re obviously much younger. They come to the place much younger and much more damaged.

There’s a reason for that, this all sort of plays into the plot because the Petros character who sort of I guess he’s based, he’s got a very thin basis on Peter Pan, but he’s a lot more sinister and his rationale for why he does what he does; he thinks of himself as quite a benevolent person. He thinks of himself as the good guy, and, y’know, any great villain in history or in comics even if you look at Magneto or Doctor Doom, they all think of themselves as benevolent and ultimately the good guy. They’re the hero of their own story. And so this is very much the case with Petros. He thinks of himself as benevolent, but also a great righter of wrongs. He feels like he needs to rebalance the cosmic scale in some ways. Although, in other ways he’s aware of his own insanity and delusion because he has moments of introspection but, like most people at an early age, whenever you don’t have someone to work that out with, he never really fully realizes it. He’s damaged.

SR: I definitely can see how he would look at himself as the hero, what with that cave full of disembodied heads that are still alive because nobody on the island can die. I feel like maybe it’s possible somebody could look at that and say, ‘this guy right here, he’s a good guy, I like him’.

Mark: (Laughs) Well, my hope for that character isn’t that anyone will ever like him. I think he’s pretty irredeemable, but my favorite storytelling always is a story that allows you insight into the antagonist, so whenever you create a villain it’s not just- there is a place mustache-twirling top-hated villain, there definitely is- but whenever I write the villain, I like him to be, if not sympathetic, at least understandable in that there is something in their motives. They’re manufactured.

I read a book recently, I don’t know if you’ve seen the Netflix TV show Mindhunter. The book is based on the experiences of John Douglas, I think he co-wrote it. The interesting thing he said about the serial killers, especially Ed Kemper, the guys he interviewed; the thing he said was that ‘these guys could’ve been something else. They could’ve been a banker, or the head of a corporation. They have this psychopathic personality type, but it was the experiences in their youth that ultimately made them what they are’. These horrible twisted versions of themselves that they weren’t necessarily on course to be that otherwise if these things hadn’t happened to them. With my main villain character, I hope that people will look at that and go ‘well, if things had to be differently, he’s not completely irredeemable’ is what I’m saying.

SR: That’s an interesting method. You’re getting into the psychology of somebody like a serial killer. Would you say that Petros is kind of like them?

Mark: Yes. I would say he is entirely like that. He’s very much like a serial killer with a god complex. I think some serial killers have that built into them, y’know they’ve got the god complex. He very much does and in many ways he is the god of the island.

SR: Are you trying to make a statement on what you think of these kinds of people?

Mark: No, not so much. Ultimately, what I want to be is entertaining. Whenever I wrote this, I wasn’t thinking ‘I want to make people question the morality of evil people’ or whatever. Obviously, I think my aim of characters is to make them strong and I don’t mean physically strong or powerful, I mean that they have to be layered and nuanced. There’s always something underneath the most puritanical person that there are. So, in this case I’m not making a statement about that Petros. I mean, if people want to research serial killers based on something that I’ve written, that’s fantastic because it’s a really interesting topic. But ultimately, this is just a piece of entertainment. More than anything I want this to be an informed idea of what this fantastical character would be like if he really existed.

SR: This superficially reminds me of what Alan Moore did with Lost Girls. You have this Peter Pan character, a more realistic version, but there’s something a little bit sinister about him. There it was a metaphor for sexual awakening. I’m not saying it’s a straight comparison, but you’ve kept this aspect of the character as a person who takes children away from their parents and they never see them again.

Mark: I think as the story progresses, you’ll learn about more, because Winter- I should mention Winter she’s the main protagonist. Winter is herself a flawed character. She’s got a lot of problems at home. This is her story, although obviously I want people to enjoy the scary angle that Petros brings to it as well. But Winter, she’s been brought to the island under false pretenses. So, most of the boys who have been brought there have been brought there, as the story goes along, it manifests that these kids haven’t come from healthy, happy homes. Petros preys on their vulnerabilities and the fact that they’re very open to the idea of leaving, getting away from their home environment if they even have a home environment, like some of them might be street urchins. So he’s very much a Dickensian type of child-snatcher.

In the case of Winter, you find out very early on, Winter has been brought there as a tribute, and she is a tribute, it’s kind of like a ritual that’s performed and she catches on straight away because once Petros has brought her there he’s got no reason to hide it, that she’s there to be sacrificed. So that’s when this story takes on a whole new dynamic, because it goes from ‘oh I’m trying to escape from my horrible home situation and I’m want to get away to this fantastical land’ to ‘Oh, I’ve been lured to hell where I’m going to be made tribute to all these cannibalistic, psychotic old men in young boy’s bodies, really, and Petros does this.

He knocks out a few of these rituals every so often just to remind everybody that it’s his cult practices that keeps everybody in line. So, that’s that other element of being a serial narcissist and a manipulator, it’s part of his personality. He’s got a god complex. So her story, it starts with her very much being a victim and feeling like she’s a victim at home and also powerless at home, and powerless in this situation, but it ultimately is the story of her finding herself and falling back on the lessons she’s learned from a family that she’s very much given up on. Hopefully it’s a horror story, but it’s also got this empowering message for kids as well, or even adults; if you’re going through something, there’s always a way to come out the other side, y’know?

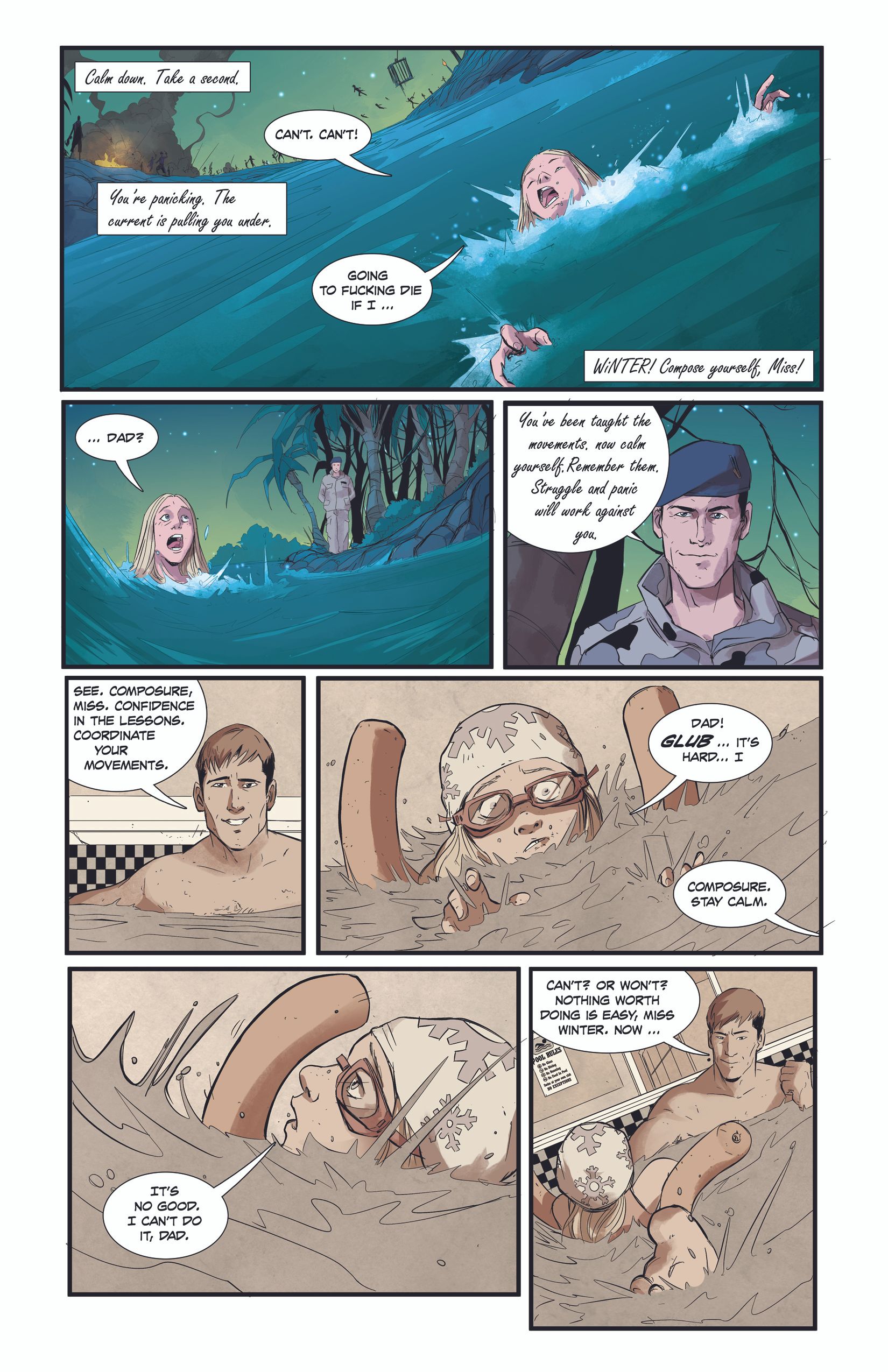

SR: Yeah, Winter is always flashing back to the lessons she learned from her family. It’s not always the best, but sometimes that’s all you can do in a bad situation, remember the times that made you stronger.

Mark: Draw on the good stuff, and both her parents are very integral characters in this in sort of a flashback sense because both of them have defined her in one way or another, just the way your parents would define you. I really dig into it here, because part of the dynamic is that her father is from a military background, and he’s very much trying to be a good dad but his wife, Maria, suffers from mental illness. I didn’t specify, but it’s largely based on bipolar disorder, and I wanted that relationship, between the three, the triangle, to be very frayed at times, with Winter experiencing her mother’s episodes, unable to understand what was wrong, seeing how much it was stressing her father, and her father trying to be there for her in spite of this, but I also wanted to show that they were all flawed, and they had fallen, dyin’ points and weak points, and there was a point for Winter when a very seductive boy-sprite sittin’ on her window sill, tellin’ her she could come and escape and that seemed like a better alternative than staying in a home that was constantly fractious and difficult.

SR: Would you say that the situation with the lost boys is comparable to growing up with a parental figure suffering like that?

Mark: Yes, that was definitely an analogy I wanted to draw in that a lot of these kids, they’ve come from bad homes or no home at all, and being brought up with no regulation in many ways is a million times worse than being brought up in a dysfunctional household. I’m not trying to make any sort of statement about parenting or anything like that. It’s just literally the case if you grow up with this pseudo-benevolent psychopath as your mentor, that is going to be a scarier more harmful experience than being brought up in a home with parents that ultimately love you. It plays into that teenage rebellious phase as well, where you just want to escape from your parents. You don’t really understand what you’ve got. For Winter, this will be a reality check in many ways, realizing that she actually does come from a very loving home, though like everybody’s family it’s not always easy, the solutions are not always a quick fix. There’s more gravity to it, there’s more nuance.

SR: There’s so much in this little parable that you’ve set up.

Mark: My hope is that- I was talking to Matt [Medney] earlier, he’s the top guy at Heavy Metal, we were having a chat, and I was talking to him about George Romero films, because I’m a big zombie movie fan. The thing I love about them is that you can view them from three angles. You can look at them as ‘it’s just a zombie movie’. You can look at them for the character moments, or you can look at them from the political standpoint. So you can enjoy it from three different ways, really. You can go ‘oh it’s just a horror movie, it’s just zombies’ or you can go ‘oh look at all these wonderful characters and how they interact under pressure’, or you can look at the politics behind it. In Night of the Living Dead, I think the politics behind it were dealing with racism in that particular era, and, you know, the ambiguity of the ending where the only survivor is killed and it’s left up to the viewer to speculate on whether they killed him because of his race or they genuinely thought he was zombie. It’s the same with Dawn of the Dead, again, it’s a movie ultimately about consumerism, about our addiction to consumer culture and I always thought Day of the Dead was a comment on the military industrial complex, but before you strip any of them down to the politics behind it, you can view the story out in front of it as just ‘it’s a zombie story, it’s got great characters in it’.

And that’s what I always try to do whenever I’m writing something; I try to write something you can look at purely as entertainment, you can go ‘it’s just a fun story with all this horror stuff happening in it’ and enjoy the character moments, or you can really plumb down into the depths and go ‘oh, he’s trying to talk about something here’. So, hopefully if it works, and I hope it does, ‘cuz I’ve got an amazing art team and editorial team, and the letterer, everyone involved is just knocking it out of the park, so my hope is that people will be able to have that three-layer nuanced view of it. And whatever way you want to experience it, if you want to experience all three, you can do that, y’know?

SR: There’s a scene where the lost boys are hunting Winter, and they end up getting disemboweled, one of ‘em gets an axe in the head. But they’re fine, because nobody can die on the island. There’s an absurdist quality but it’s just so freaking scary.

Mark: Good, I’m glad, that’s exactly what I was going for. The thing about these guys, these lost boys, I sort of call them feral kids or whatever, I wanted them to be the most terrifying- if you can imagine a boy who has evolved into man, whose brain has majored into a man’s brain in many ways, obviously not for hormones and stuff, but it has aged and it has been fermenting in this sea of madness on this island for maybe decades, maybe longer, and what would that look like? A pre-pubescent matured brain in the body of someone who’s grown up in utter lunacy? This little body that never ages? It’s like a whole new thing, and these guys cannot die because of the environment they are in. They can get injured, they can get messed up but unless you completely reduce them to dust- and even then that spiritual aspect of them will linger- but you can’t kill people on this island. But they can suffer.

Everyone can feel pain, it’s like Wolverine. If you ever read a Wolverine comic you know he takes tons of damage and he suffers throughout it, and he heals and stuff. But in this case, they’re not healing with any sort of great speed, they don’t have the nutrition in their diets, so they look like starved cannibals. And whenever they get mangled or messed up, that stays with them usually forever. I wanted them to be scary, scary characters: the type of thing if you saw it, it would just turn your blood to ice. And they can fly, so that makes it worse.

SR: Why do you have to make the heroes suffer so much as well?

Mark: The reason I make the heroes suffer so much- I am very much from that old school of Stan Lee-thinking where you have to… well not even. If you go way beyond, way, way further back, you go back into the Greek myths and things like that… it’s the hero’s journey. Everybody has to go through that hero’s journey in order to come out the other end. I hear a lot of criticism nowadays about these characters who don’t go through a lot, they sort of come out unblemished. They get an easy ride of it, they get called Mary-Sues or whatever. Whenever I set out to write this, I was like ‘listen, this character is going to suffer. It’ll be a physical and spiritual journey for my character. It will be an epiphany so that whenever they come out the other end it really is going to be this massive overhaul of how they are.

So it’s a hero’s journey and I wanted to play it real. I wanted to play it for keeps. One of my favorite books for a long time was Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead, and I loved the way that no one was safe. Rick gets his hand cut off, Carl loses an eye. Nobody was safe and that made it real. It made it scary and that meant that whenever you tuned in you were always on the edge, wanting to know what was going to happen next, ‘how are they going to get out of this?’, and I very much wanted that to be the case for my character. I wanted her to be forced into positions where you don’t know. She might not make it out of this in the same shape she came in. It really is a perilous journey.

So yeah, I like suffering characters, I like the Peter Parker-archetype, where everything goes wrong and he has to pull it out of the bag, he has to have the Hail Mary play, or that last minute comeback stuff. I love it. I love that underdog vibe. So, that’s what I’ve tried to do with Winter. I should mention this as well: one of my favorite movie characters was Katniss Everdeen. Now, I’m not a massive fan of The Hunger Games. I think they’re good movies, that they’re sort of fun, but they wouldn’t be my favorite. I liked her as a character because she is resilient but incredibly flawed, and things don’t always go her way. There’s times when you see her and you think ‘oh, she’s not going to make it out of this’. So, I liked the idea that Winter, as a young girl, is in way out of depths. She’s in deep, deep shit. She’s up to her neck in shit. Realistically, how do you get out of that unscathed? You can’t. So, I thought, she’s going to have to suffer a bit to get out of this and I want her to really go on that developmental journey. I want her to come out the other side changed, if she comes out the other side at all. But I’ll keep that one under wraps.

SR: That word you just used: ‘I want it to be real’. In terms of the world, no matter how absurd, bizarre, nightmarish this is, the one thing at the core you’re trying to say is ‘it’s real’. What is ‘real’ in this context?

Mark: I guess for me, why did I want to focus on the reality of this situation? I guess, in some ways… obviously in western society, we’ve got our problems, we’ve got some awful stuff. But this sort of horrible lifestyle isn’t off the cards for some people out there. For instance, if you went to Syria right now, there’s some awful stuff happening, just beyond our comprehension. That sort of stuff really exists out there. It’s a level of horror we can’t fathom. So, again, it’s not me making a social comment per se, it’s me saying that there horrors out there that we can’t imagine and they’re so deeply effecting.

And that’s what good horror is to me. It’s something that hits you in a primal level. It’s something that feels like it could happen. It’s something that you palpably feel in your blood, that raw terror, this could really be a thing. So, whenever I read a book on serial killers, or witchcraft or demonology or stuff… periodically I’ll read these things and I’ll read stories about warfare and all these things, and you pick up these snippets, these absolutely horrible snippets of real experiences that people have had. And they’ve haunted me way worse than something I’ve seen in a movie, or something I’ve read in fiction. So what I wanted to do was I wanted to write something that felt like, even though it is entirely fictitious, I wanted to draw on those elements that hit you primally. They hit that raw nerve and may you go “OH”. Make you uncomfortable in a genuine way. I wanted to draw on those. And put them into the book, because that’s what anybody who writes in the horror genre is really ultimately trying to do and that is just scare the shit out of the audience. Do something that feels so real and uncomfortable to them that they have nightmares about it.

Never Never #1 goes on sale August 12th, with art from Phil Buckenham, colors by Agnese Pozza and covers by Christopher Lair from Heavy Metal Publishing.