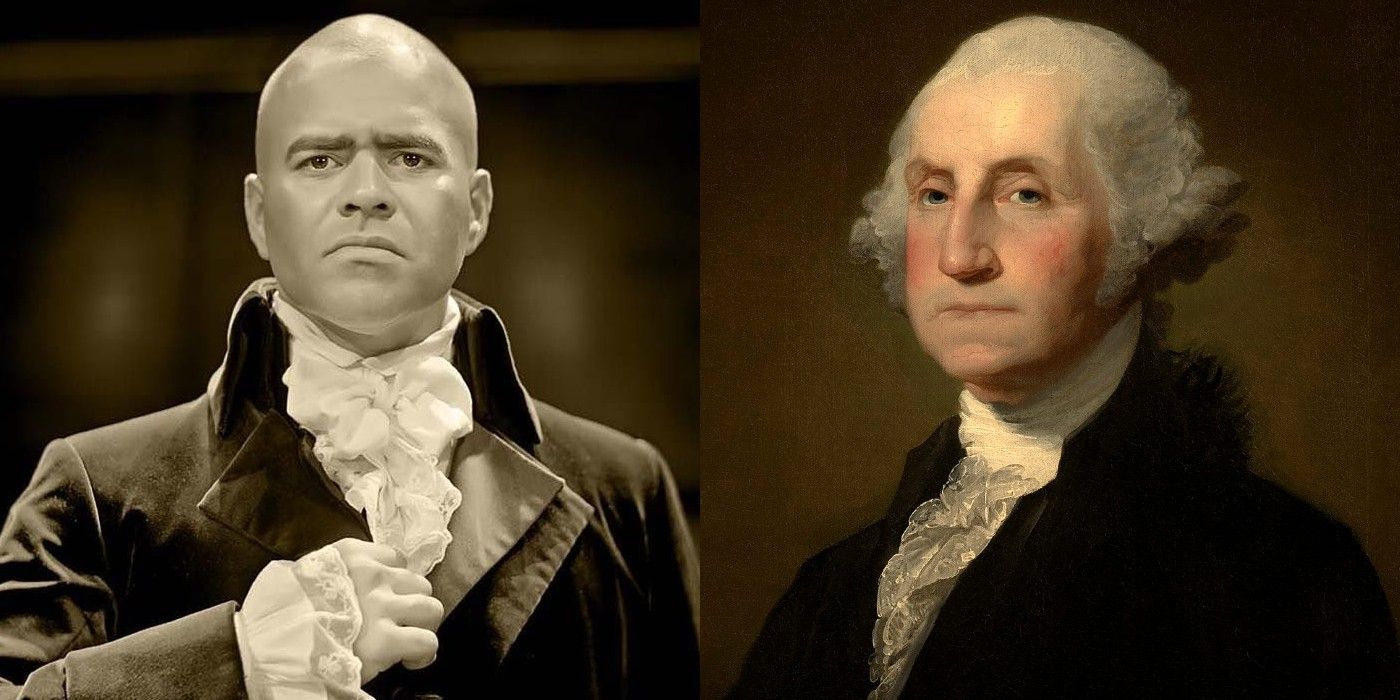

Amid Hamilton’s most widely debated controversies is the musical’s portrayal of George Washington, which leaves out much of his personal and professional life in favor of illustrating his close companionship with Hamilton himself. Since its recent release on Disney+, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton has reignited the world’s infatuation with the hit Broadway musical, which took the 2016 Tony’s by storm and has boasted consistently sold-out shows ever since. But despite the praise, viewers and critics alike have voiced concerns over the musical’s historical inaccuracies and how they may warp audiences’ perception of American history.

While conversation regarding Hamilton’s problematic portrayal of historical events began far before the musical’s debut on Disney+, recent protests and invigorated attempts at removing Confederate monuments have granted the discussion a pressing, more politically charged sense of urgency. Critics, historians, and Twitter users alike have questioned the show’s glorification of Hamilton and other Founding Fathers, particularly in the exaggerated extent to which they seem to oppose slavery. Miranda, having found inspiration to write the show after reading Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography Alexander Hamilton, has stated in multiple interviews that he “felt an enormous responsibility to be as historically accurate as possible” (via The Atlantic). Yet, as a piece of historical fiction, Hamilton is bound to take a few creative liberties, and Miranda’s portrayal of George Washington is no exception.

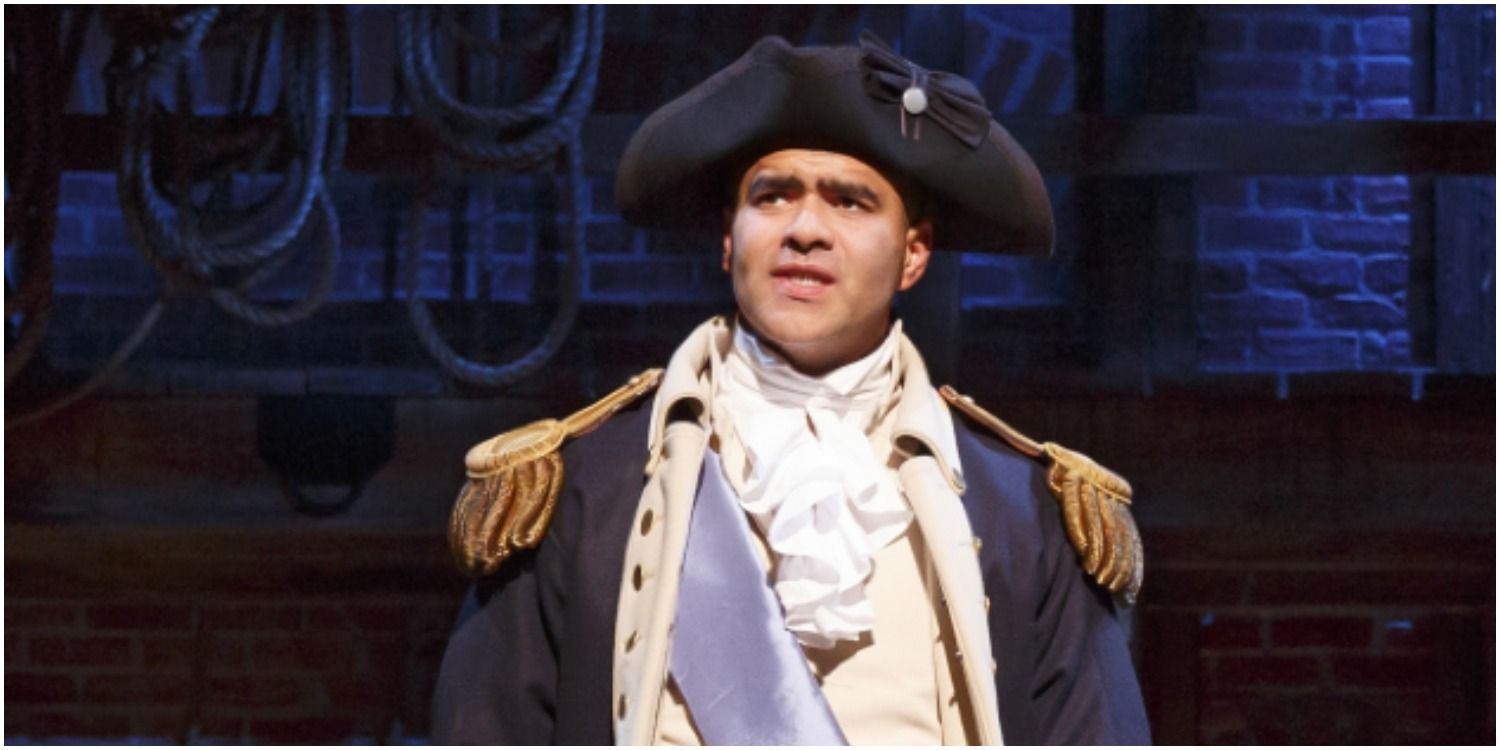

Hamilton’s most obvious deviation from real-life events is its use of race-blind casting, with many of its major historical figures portrayed by racial minorities. While the show’s attempt at modernizing history through diverse casting and hip-hop was a welcome change, it may have come at the cost of historical accuracy. Despite Hamilton’s role as Washington’s “Right Hand Man” being a major component of the musical, Miranda left out many key details of George Washington’s life that weren’t quite as rosy as the duo’s on-screen, father-son dynamic.

George Washington Owned Slaves

Despite Hamilton’s willingness to portray Alexander as a fervent abolitionist, his complicity in the system knew no bounds, particularly when it came to George Washington. After Washington’s father died in 1783, he was willed the 280-acre family farm in Virginia along with ten slaves, all at the tender age of 11. He continued to acquire slaves as a young adult, both through the death of family members and direct purchase. His marriage to Martha Custis also contributed significantly to Mount Vernon’s enslaved population, as she brought with her approximately 80 more slaves. By 1789, Washington became the first president of the United States, with his plantation and sanctioning of slavery doing little to diminish his popularity among voters. By the time of Washington’s death in 1799, the enslaved population at Mount Vernon consisted of 317 people, nearly half of which Washington personally owned. While he was unwilling to relinquish his ownership over these slaves while he was alive, Washington left orders in his will to emancipate the people enslaved by him upon the death of his wife.

While slavery is mentioned several times throughout Hamilton, and other characters besides Washington (including Philip Schuyler, the Schuyler sisters’ father) were guilty of owning slaves, there is no enslaved voice in the musical. In a 2016 interview for Slate, historian Lyra Monteiro points out the issue with this while discussing the show's penchant for diverse casting. She suggests that it gives Hamilton the ability to say:

“‘This isn’t your stuffy old-school history that’s just praising white people. Look, we’ve got people of color in the cast. This is everybody’s story.' Which, it isn’t. It’s still white history. And no amount of casting people of color disguises the fact that they’re erasing people of color from the actual narrative.”

Those who disagree, however, believe Hamilton was a star-making opportunity for actors who didn’t fit into the white-washed Broadway scene. Others, like Okieriete Onaodowan – who portrayed James Madison – believe the show’s erasure of slavery intentionally points to other pressing issues of systematic racism in the U.S. In an interview for Vulture, he states that, “In the inception of our show, by the omission of that story, it kind of highlights the problem. It’s getting black kids interested in history to ask the question why they aren’t in history.” In this way, they may feel inspired to research other predominantly BIPOC historical figures not taught about in schools.

In reality, George Washington’s history as a slave-owner is far more extensive than Miranda’s Hamilton leads viewers to believe. While the show glosses over the horrors of slavery and Washington’s complicity in the system, it never claims to glorify the Founding Fathers. Hamilton himself, despite being idealized as an eager, underprivileged immigrant at the start of the musical, is no hero – after all, he was partially responsible for his son’s death. Regardless, for such a modern take on a historically white-washed topic, Hamilton might’ve benefited from a more inclusive narrative.

George and Martha Washington’s Marriage and Children

Hamilton is perhaps most infamous for its “star-crossed lovers” story, featuring a love triangle between Alexander Hamilton, Eliza Schuyler, and Angelica Schuyler. While the characters’ real-life counterparts weren’t quite as theatrical in their romantic pursuits (despite Renée Goldsberry’s performance of “Satisfied” leading us to believe otherwise), Miranda missed out on the chance to tell another notorious love story – George and Martha Washington.

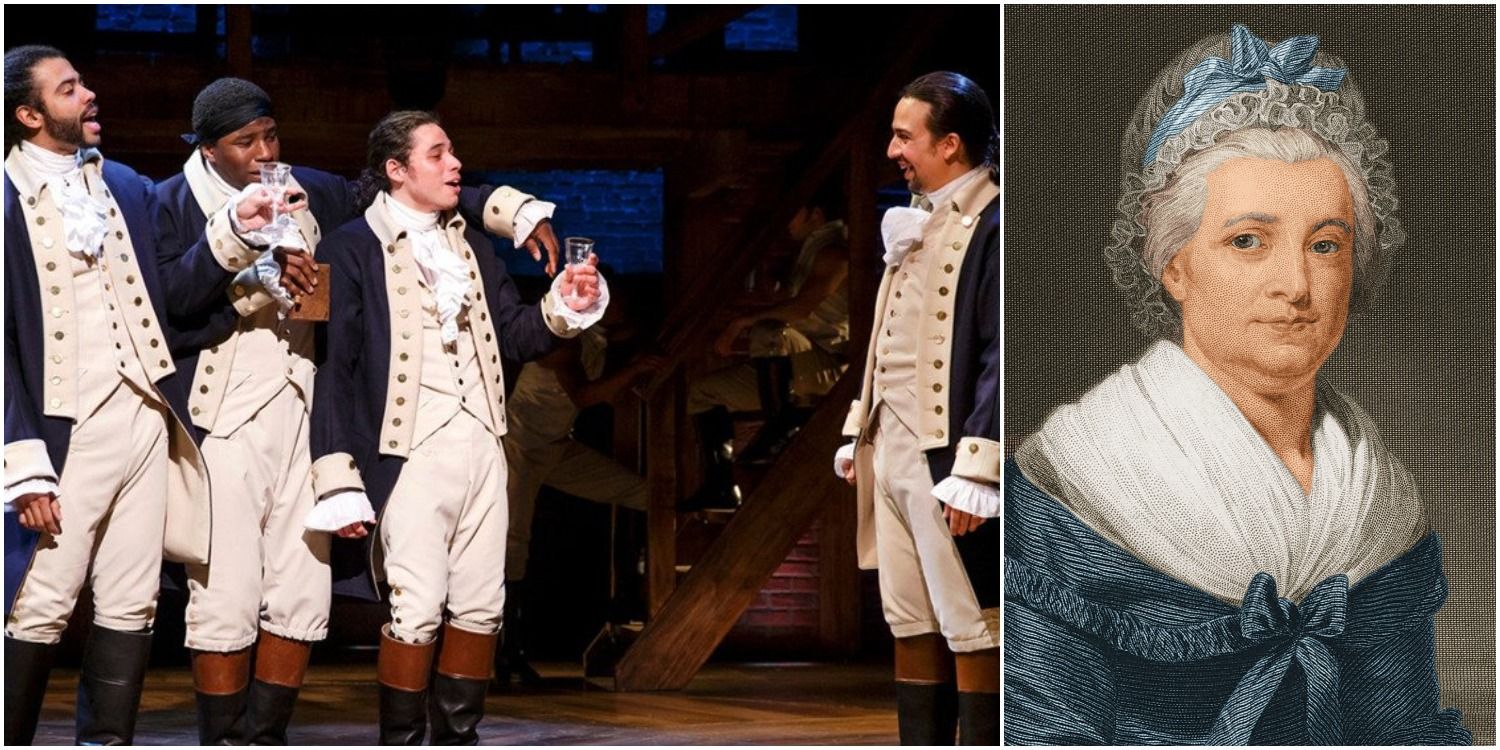

George and Martha’s relationship would’ve never existed if it hadn’t been for the death of Martha’s first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, in 1757, leaving her an extremely wealthy widow. While Washington wasn’t quite as high up on the social or financial hierarchy as Martha, the two were undeniably attracted to each other and began a courtship in 1758. By 1759 the two were married, relocating to Mount Vernon the same year. Martha was exceptionally supportive of George throughout their marriage, particularly during the war. In a letter to his own wife regarding the many officers requesting their wives join them for the winter, Marquis de Lafayette (portrayed by Daveed Diggs) noted that, “General Washington has also just decided to send for his wife, a modest and respectable person, who loves her husband madly…”

While George had no biological children of his own, he served as a beloved father figure to Martha’s children and grandchildren throughout their 40-year marriage. Though the exact reason is still unknown, Washington left no trace of having regretted this aspect of his life – in fact, this might’ve been a reason why Miranda chose to exclude it from the musical, as both Hamilton and Burr’s relationship to their children was vital in the development of their romantic partnerships. Martha Washington passed away a few short years after George in 1802, and the two still lay side by side today at the new tomb on the Mount Vernon Estate.

Bribery and Washington’s Political Criticisms

Though Washington is depicted as a wise, fearless leader in Hamilton, the real George was no exception to political corruption. The practice of using booze or food to sway an election dates back to the days of America's very first president, at which time the method was called “swilling the planters with bumbo” – bumbo being the type of rum, and planters being the landowners who could vote. After attempting to win fairly while running for Virginia’s House of Burgesses in 1755 (and losing), Washington realized plying the masses with liquor was the way to go, finding that a half-gallon of booze per voter did the trick during his next run for elected office.

At the time of his inauguration, George Washington was almost universally glorified by national press, widely considered the best choice for the position at the time. However, increasingly hostile press attacks quickly gained traction by his second term, and are thought to have been a major reason behind his retirement (which was more than just a noble act of patriotism, as Miranda’s “One Last Time” implies). Most criticisms revolved around Washington’s “monarchial” style and “aristocratic” behavior, which wasn’t at all helped by Hamilton’s plans for a new economic program. By the end of 1792, there was a recognizable opposition party led by Thomas Jefferson (Daveed Diggs), who Hamilton later endorses in the musical during “The Election of 1800.”

Hamilton and Washington Weren’t Friends

This one might be a heartbreaker for many die-hard Hamilton fans – while George Washington and Alexander Hamilton worked in close proximity for years, they never became close friends; their different positions and opposing personalities prevented it. Despite this, they shared a valuable professional relationship. Washington gained a quick-witted, brilliant administrator able to bring order to the chaos that was his army, later doing the same to an entire government. Hamilton, in turn, gained a sort of patron in Washington – a “shield” that granted him a well-respected position wherein he would be protected from the criticisms his revolutionary ideas inevitably caused.

Since the show takes place from 1776 to the early 1800s, it makes sense that Lin-Manuel Miranda didn’t incorporate every detail of Washington’s life into Hamilton. While the musical takes some creative liberties in dramatizing certain events and completely erasing others, there is much to be said when it comes to its educational, artistic, and historical significance. Even though viewers may have to do their own research if they want to know the full story, the show is arguably a valuable contribution to representation and diversity in theater.