Article updated: September 27, 2020

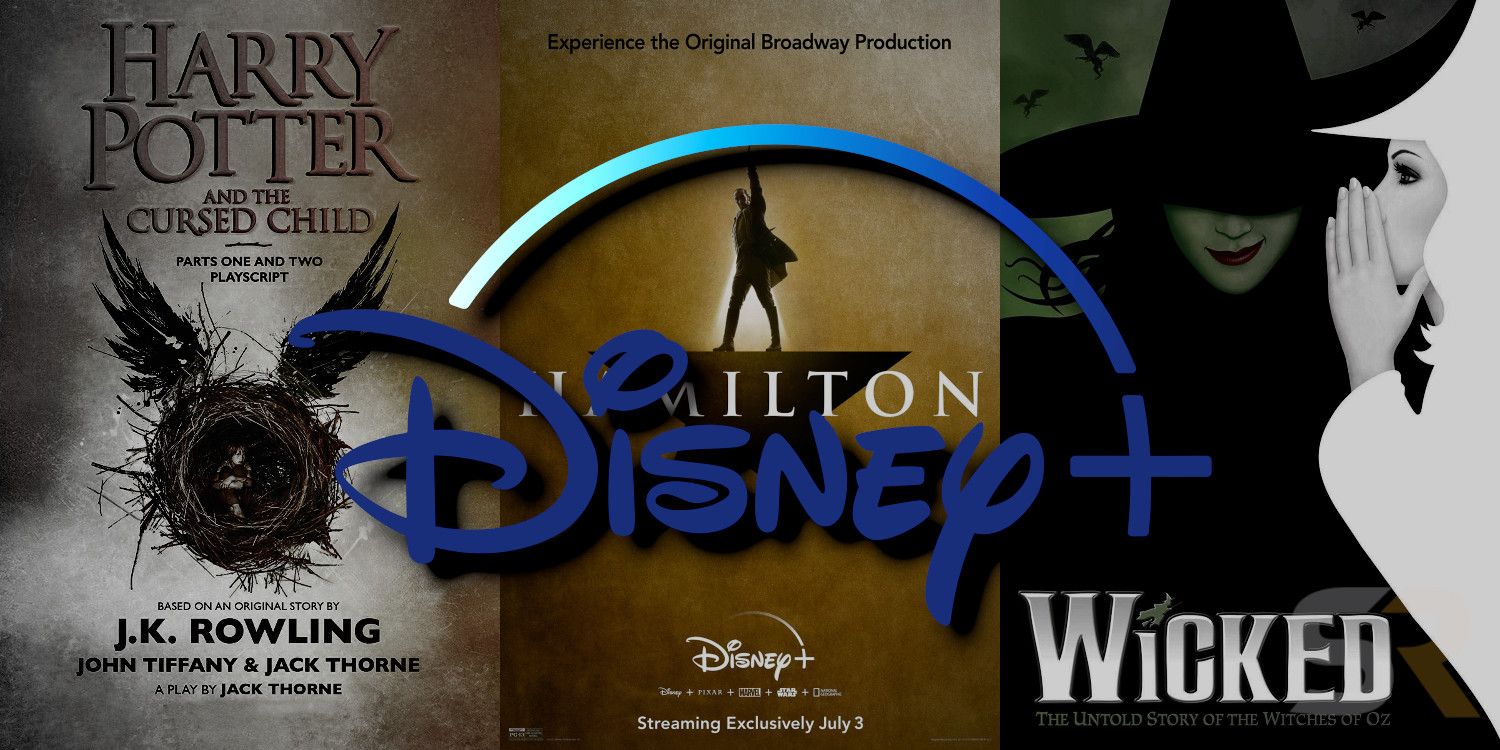

The original Broadway production of Hamilton became available to stream on Disney+ in July, and its popularity has raised the question of why more Broadway shows aren't available to watch on demand. Hamilton is not the first Broadway show to be filmed and made available on streaming services, but its widespread popularity and financial success made it the first major musical on demand. The Broadway League has resisted the transition to streaming for years, speculating that increased access to musicals would cause ticket sales to plummet - but Hamilton's continued global success is a sign that viewers are ready for more access to Broadway.

Broadway might have resisted making musicals available for filming and distribution, but there are still a few notable exceptions. The Disney musical Newsies was released on Netflix in 2017, and Kinky Boots and Falsetto are recent additions to the small streaming service BroadwayHD. Much like Hamilton, these musicals are the exception, not the rule. After Broadway shut down in March due to the coronavirus pandemic, and Hamilton saw overwhelming success on Disney+, fans speculated that Broadway would gradually begin releasing musicals on streaming. This long-anticipated move would help make theater more accessible and help shows make money during the Broadway shutdown, which is currently scheduled to last until January 2021.

However, that shift hasn't happened. Although at least one other Broadway musical will be debuting on Netflix, Diana, there has not been a major shift to release any more musicals on demand. Legally Blonde was released on DVD before the national tour and saw a major increase in ticket sales, proving that the ability to watch a musical at home only makes the show more popular - not less. Hamilton became a movie despite major challenges because it was already massively popular and was able to finance the production - but most musicals can't. Here's the real reason why Hamilton became a movie, and why the rest of Broadway won't do the same.

Hamilton Proved It Was Worth $75 Million

When Disney announced that a filmed version of Hamilton had been taped with the original Broadway cast and would be released in theaters, the musical was already successful. Hamilton grossed $649.9 in domestic ticket sales according to the Broadway League, and over $1 billion worldwide (via BroadwayWorld.) Hamilton also reached that goal within five years of its opening date on Broadway, while the three highest-grossing musicals of all time (Lion King, Wicked, The Phantom of the Opera) are all more than sixteen years old.

However, Hamilton's massive financial success is an outlier. Broadway shows cost between $10-20 million to produce, and only 21% of musicals recoup that investment. Hamilton's $75 million price tag for movie rights increased its costs significantly, but the show's global success meant that the musical had a built in audience on Disney+,and the financial risk paid off. Hamilton finally became accessible and was watched in 2.7 million households the first weekend it was available to stream.

Hamilton's success on Disney+, combined with the extended Broadway shutdown, makes putting musicals online seem like the obvious choice. However, Hamilton was only able to be filmed and produced due to the musical's unique circumstances: it's mainstream popularity, which most shows do not have, it's massive financial success, and it's availability on Disney+ instead of the more niche streaming service BroadwayHD. Still, Hamilton was able to overcome the financial hurdles. Why can't something like Wicked become a movie, too?

Most Broadway Musical Rights Prohibit Streaming

When a musical is performed on Broadway, it's done through a licensing deal: a contract allowing the show to be used in a live performance. These rights are known as the "grand rights" and exclude (or outright prohibit) streaming or filming permissions. Licensing companies have only started putting together streaming packages for shows as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, when they began receiving pressure from theaters that had been forced to close. Even after that shift, most popular shows are not licensed for streaming.

Streaming rights for musicals break down into three categories: live-streaming, scheduled streaming, and streaming on demand. The most common type, live streaming, is literally watching a live-feed of the show as it's performed - this is what most regional and community theaters were able to do in March. Less common and more expensive, scheduled streaming means taping a show once and making the video available at a certain time or during a small time period to ticket holders. The rarest, streaming on demand, is what Hamilton accomplished, and the option is almost never available in a licensing package. On top of that, streaming licensing is almost never available if a musical is begin optioned for a movie adaptation, or already has one. This is why The Prom, which Ryan Murphy is turning into a movie for Netflix, or Wicked, which has been in development limbo for years, are still not available to stream.

In addition to the licensing hurdles, Hamilton had to make agreements with several different labor unions in order to film and release the musical. Every part of a Broadway show is under a union contract (choreographers, musicians, technicians, etc.) including the Actors Equity Association, which covers the cast. In film and television, these roles are covered by SAG-AFTRA and the WGA, whose contracts already have built-in stipulations for upfront costs and residuals. Not all organizations should be seen as an impediment, though, and certainly saying they all "oppose" digital rights is not correct. The Dramatist Guild plays a crucial role in helping facilitate agreements over digital rights and is creating new a new model for digital rights agreements for the future use of their members, and while current agreements do not discuss the issue of digital rights, they do allow producers the right of first negotiation.

Unlike in television, Broadway contracts only cover payment for a live performance, and unions rarely allow streaming permissions. In addition, some aspects such as lighting have to be redesigned in order to film the show - which means negotiating a second, more expensive contract with the designer. Even if a musical can reach an equitable agreement with the labor unions, it drives the cost of filming and production up significantly - an issue even Hamilton ran into, in contract negotiations with star Leslie Odom Jr.

Every Broadway Show Is Filmed But Inaccessible

Although Broadway shows often prohibit streaming, every musical is filmed purely for archival purposes. Since 1970, the New York Public Library has maintained the Theatre on Film and Tape Archive, which is made up of over 5,000 taped recordings of Broadway musicals and plays. Unlike Hamilton's professional quality, these recordings are made from a grainy, single-camera set up at the back of the house. For comparison, Hamilton had a three-camera setup, redesigned lighting for film, and high-quality audio and sound. These archival videos are intended only for research purposes, not for public consumption.

The New York Public Library also makes it very difficult to watch the videos. The entire archive is under restricted access and cannot be checked out. With a New York Public Library card, most of the videos can be seen in person at the library (although some require special permission), and all require an appointment for researchers to view them. While musical fans have requested that the videos are released, they are nowhere near the same production value as Hamilton.

Live TV Musicals Are The Next Best Thing

It's easy to see how Hamilton is the rare Broadway musical to be professionally filmed and released, and how other Broadway musicals are prevented from doing the same. However, another innovation has brought Broadway musicals back to the forefront: live TV musicals. From 2013-2019, ten musicals were produced and broadcast, including The Sound of Music with Carrie Underwood and Jesus Christ Superstar Live In Concert with John Legend. Unlike filmed versions of Broadway shows, these productions are specifically licensed and designed for television.

Live TV musicals are the next best thing to Broadway shows, and are separate productions specifically created and contracted for filming and live broadcast. By producing a completely separate production for broadcast, they avoid the labyrinth of licensing and contract issues that Hamilton had to go through. Producing a live musical for television is still costly - Fox's production of Grease cost around $15 million. Live musicals still accomplish the basic goal of making Broadway more accessible to a broader audience, and takes musicals out of the insular New York bubble.

The reason Broadway has pushed back on streaming is the fear of cannibalizing ticket sales and incentivizing fewer people to see the show. Producers are already reluctant to release any videos until a musical has closed on Broadway and is no longer touring, but that fear was disproven with Legally Blonde and the boost in ticket sales following the DVD release. The Broadway League saw major pressure to make musicals available on-demand after the Broadway shutdown, which is currently scheduled until January 2021, but the prohibitive cost means many musicals will never be available on streaming. For now, musicals fans will have to be content with the limited offering on Broadway HD or Disney+, or rewatch Hamilton yet again.

---

This article was updated to clarify the objectives and operations of the Dramatists Guild and to include official comment from the Guild's Executive Director for Business Affairs, Ralph Sevush:

The Guild is not a labor union; we are a voluntary membership association. The Guild contract that is used by our members for their Broadway productions does not discuss digital rights, it simply reserves audio-visual rights to the authors while providing producers with a right of first negotiation to acquire those rights. Dramatists can do what they wish with their reserved rights. And, rather than opposing the licensing of such rights, the Guild is facilitating it by creating new model digital rights agreements for our members’ further use.