Science fiction has always been a bit nebulously defined as literary subgenres go - at one point exclusively referring to a then-new style of writing where the narrative chiefly existed to speculate on the use (or misuse) of some new hypothetical technological concept, but soon expanded to include just about any flight of fancy where the fancy in question was ostensibly grounded more in "science" than explicit mysticism. Over time, a common (but by no means definitive) definition emerged that held at least "quality" sci-fi to be framed as a story that uses a speculative scientific conceit (or series of the same) to explore a theme either symbolically or through tendering of the "logical extreme."

For example: the original Star Trek is "about" the politics and geopolitical machinations of the world in which it was created, rendered in an imaginary possible future and set among hypothetical new planets. Planet of The Apes was about debates over who controls the "truth" of historical record. The original Godzilla was an attempt to "process" the aftermath of Fat Man and Little Boy in the form of a monster story. H.G. Wells' War of The Worlds was about showing contemporary British readers what it might feel like to be on the receiving end of colonialism (and how tenuous an extended "empire" could be.)

Most science fiction, in other words, is about something other than the literal premise of its plot; which means that often two otherwise wildly different works linked on by the sheer broadness of the genre itself can actually be covering effectively the same material (example: Jurassic Park and Ex Machina - think about it.) And sometimes they land in such proximity so as to compare them against one another.

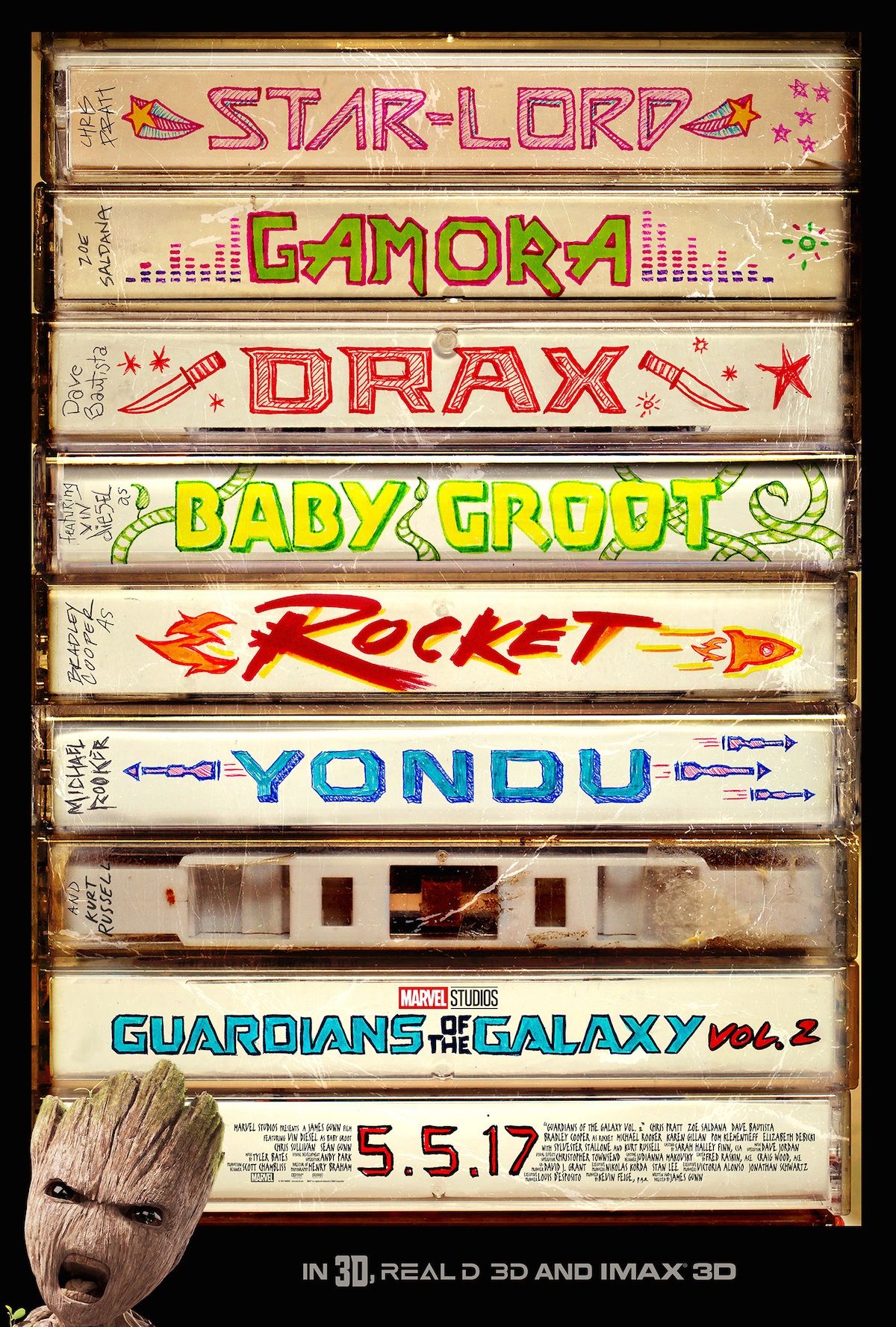

To wit: Guardians of The Galaxy Vol. 2, a sci-fi comedy starring a foul-mouthed space raccoon tangentially linked to a series of colorful superhero movies, and Alien: Convenant, a dark and studiously self-serious film starring Academy Award darling Michael Fassbender directly linked to one of the most respected franchises in the history of the genre; are both currently playing in theaters worldwide and are both covering surprisingly similar topics in terms of symbolism and metaphor. But which one actually does so in a more compelling and resonant way is just a bit surprising - and it's fascinating to consider just how that happened.

DADDY WASN'T THERE

Let's get right to the meat of it: Guardians of The Galaxy Vol. 2 and Alien: Covenant are both "bad dad" movies, where abusive/absentee fatherhood and the instinct to view fatherhood as an extension of the self are at the core of the villains motivation and backstory.

Interestingly, they both do so in the context of "following" stories that are were mainly about mothers: The Alien franchise is infamously preoccupied with pregnancy symbolism (even Prometheus' signature moment is the abortion of a monstrous "fetus"), while the original Guardians was all about Peter "Star-Lord" Quill growing up beyond mourning his lost mother - hence why Gamora isn't interested in "dancing" (as Drax the Destroyer would say: "Metaphor!") until he finally opens what turns out to be "Awesome Mix Vol. 2" - symbolically accepting that she is dead and that he can live on from that.

It while both films are very, very cross with their respective disappointing patriarchs; they get there in very different contexts and with decidedly divergent (in terms of intent and success) results:

GOD, COMPLEX

In Covenant, we have several Bad Dads mulling around the plot - first and foremost, the "Father with a capital-F" himself, God, whose influence in the form of fate and cosmic "justice" is alternately questioned, doubted and mourned by the terminally unlucky crew of The Covenant and invoked via the leftover plot threads from Prometheus; where the eponymous crew came to learn that The Father's "actual" identity might have been one of the Engineers - a race of musclebound albino space-biologists who went around conducting genetic experiments on young planets.

God is also the "Bad Dad" in turn invoked by The Covenant's interim Captain (Billy Crudup), a devout Christian (implied to be a persecuted minority in this future, one of many ideas the film raises and then does absolutely nothing with); himself a "Bad Dad" to his crew whose decision to let Jesus take the wheel when it comes to exploring a suspiciously-habitable planet spells doom for everyone involved.

Our ultimate Bad Dad, however, is David (Michael Fassbender), the android antagonist from Prometheus who is himself the product of two other Bad Dads: His creator Mr. Weyland (Guy Pearce) and - once again - God Himself, whose identity Weyland was obsessed with sussing out and whose (literal) world-building machinations David aspires to.

David, we learn, has been busy since Prometheus: Carrying out a genocide of the Engineer planet (and butchering Noomi Rapace's Elizabeth) in the name of conducting animal-husbandry experiments that have resulted in the cultivation of what we recognize as the traditional "Xenomorph" Alien. No, really: The minblowing reveal that was worth scuttling the mystery of the Alien franchise for turns out to be "a malfunctioning robot made them because he was programmed to be curious but not to not murder everything - oops!"

But what does giving the Xenomorphs a "father" after all this time associating them only with their Queens actually add to the proceedings? It's not entirely clear. The whole point of David as a villain is that he doesn't really have a "psyche" - just bad programming - and for all the high-minded name-drops to the Judeo-Christian mythos and various artworks and poems related to the same Convenant seems so unconcerned about it's own deeper implications that its one explicitly religious-adherent character never even finds out about The Engineers. What seems to be pointing to a Big Statement about the nature of Man & God ultimately wraps up as just another Alien movie... but where the Alien itself has been stripped of its vital unknowableness.

"SMALL G, SON"

By contrast, Guardians' central "Bad Dad" is a lot less mysterious upfront: Kurt Russell's Ego: The Living Planet is a brain-shaped cosmic supervising called a "Celestial" who has formed an entire world and ecosystem around himself as a moon-sized protective shell and set out among the stars via a humanoid avatar in order to encounter and understand other forms of life - a journey that included meeting Meredith Quill on Earth and fathering the half-Celestial Star-Lord.

In its way, that's not much "more" pulpy and high concept than Covenant's mass-murdering broken robot - it's just less layered in stone-faced self-seriousness: When one of your main characters is a talking space racoon, you've got the wiggle-room to make your villain a giant talking planet named for the singular emotional concept he embodies - call it refuge in audacity.

But Ego isn't "only" ego, he's representative of the specifically masculine ("macho," if you like) permutation of the idea: We soon learn that he was quickly let down to discover that not all life in the universe was as "perfectly" self-realized as himself (one could probably write an entire encyclopedia on the subject of prideful male obliviousness based on Ego's insistence of himself as "self made" but also unaware/unconcerned with his actual origin) and decided that he would instead seek to consume and replace all known worlds with extensions of himself - to which end he went about fathering thousands of would-be demigods (like Peter Quill).

Oh, and should anyone in the back of the theater manage to "miss" that the Guardians are now up against the embodiment of toxic-fatherhood (toxic masculinity period, really), it turns out that the moment he felt close to questioning his conqueror-instinct thanks to the pesky feminine emotion of "love," he snuffed it out by infecting Star-Lord's mother with the cancer that killed her - a fact that he's exactly arrogant enough to reveal and turn Peter fully back against him. Why, oh why, can't he just understand that she was potentially in the way of his desperate need to make himself matter by leaving his mark everywhere?

Next Page: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='OF%20COURSE%20I%20HAVE%20ISSUES%20-%20THAT%27S%20MY%20FREAKIN%27%20FATHER']

"OF COURSE I HAVE ISSUES - THAT'S MY FREAKIN' FATHER!"

There's a lot to unpack in that, as there is in Covenant. But where Covenant is content to let it's "big idea" (David as curious but empathy-deprived creator-god) sit as pretentious thematic window-dressing on what turns out to be an otherwise straightforward mad scientist story - basically "The Planet of Dr. Moreau" - Guardians builds it's entire narrative around exposing Ego's version of fatherhood as toxic and destructive; particularly when weighed against other examples in the film.

Most prominently of course is Yondu, the space pirate who raised Peter as one of his Ravagers after (it turns out) kidnapping him on Ego's behalf but learning that The Living Planet has been killing the offspring who don't reveal themselves to be extensions of his own interests. Recognizing Yondu as a "good" (if imperfect) father is Quill's true arc in the film, slyly foreshadowed by learning earlier that Drax - whose species is incapable of interpreting the world non-literally - had assumed Yondu was his father all along (also from Drax, on hearing Peter derisively compare him to 'an old woman': "Because I am wise?")

But it's ultimately Star-Lord himself whose paternal behavior as "father" of his mixed-up team of Guardians gets held up as the anti-Ego ideal. Surrogate families are the Marvel Cinematic Universe's favorite theme (Captain America and the Howling Commandos, Phil Coulson's misfit Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Ant-Man's happy Mom/Dad/Stepdad/Kid/Giant Ant coda and of course The Avengers themselves); but Guardians Vol. 2 is the first time one of these alternative families (the Guardians having been rendered more explicitly so in the way they all take turns "mothering" Baby Groot - in case you thought that character was only there to be cute) have been pitched in battle against a symbolic stand-up for something more "traditional."

Make no mistake: That's ultimately what Guardians of The Galaxy Vol. 2's big final battle against (and within) Ego boils down to: A post-nuclear "adopted" family smacking-down the cosmic embodiment of what's commonly referred as "patriarchy" (small-p).

BOOK OF DAVID

To be sure, Covenant has similar (and similarly weighty) themes on it's mind - it just goes about them in a much less fully realized way that, paradoxically, calls vastly greater attention to their presence: You don't have to consciously recognize Star Lord becoming the better father to his team by rejecting the toxic-masculinity model of his own father to understand it, be moved by it or even just enjoy it as spectacle.

By contrast, Covenant won't let you forget that it's trading in Biblical allusions and English Lit 101 allegory, or how portentous and meaningful all the sturm und drang is meant to be. But despite how often Michael Fassbender dryly intones to any character who'll listen (or to the audience) that he's a Bad Dad whose self-regarding abusive "parenting" (both of his parasite "children" and his own at the hands of the indifferent Mr. Weyland) has loosed monsters on the galaxy there's nothing really there beyond the text.

There's certainly opportunity: If the Xenomorphs are a plague on the universe unleashed by a careless creator-god, what makes them noticeably different from humankind? - but Alien: Covenant is almost proudly disinterested in acknowledging or exploring it in any meaningful way. We learn where The Alien came from, but instead of imbuing it's actions with greater depth it just serves to deflate the impact of what remain more than ever a collection of jump-scares. Information without meaning is just data, and if data were compelling on it's own it wouldn't be data (that's why Star Trek: The Next Generation named the "interesting" android Lore...)

MANIFEST DESTINY

Though most prominent, toxic paternalism is hardly the only theme the two films share in common. They're also concerned with broad metaphors for the legacy of Colonialism: The respective Bad Dads are also ugly specters of frontier-conqueror archetypes, David the posh-accented British Imperial-Adventurer who sees every being and culture he encounters as a resource to be toyed with and "bettered" through his interference, Ego the swaggering Cowboy seeding "order" across the galactic wilderness. But even there, the dynamic is the same - both films raise the topic, but only Guardians actually bothers to explore it beyond a vague, implicit "think about it, won't you?" hovering in the silences between Covenant's terse dialogue exchanges.

You might think someone among The Covenant's crew of literal, self-described colonists might have some thoughts on encountering the logical extreme of their own mission (having decided that his Xenomorph "children" are the superiors of humans, David now wants them spread far and wide); but if they do no one bothers to bring it up - that might pull time away from more important scenes like Michael Fassbender teaching himself to play the recorder. Guardians, on the other hand, doesn't even treat its central joke (matching seemingly-incongruous late-70s AM radio rock with sci-fi sequences) as being exempt from reinforcing its bigger themes: Ego's grand "I am actually the bad guy!" speech arrives in the form of cheerfully deconstructing one of Star-Lord's beloved "sensitive guy" soft-rock tunes, "Brandy," as (correctly) a self-aggrandizing ode to guys who, like him, are just too cool and important to be "tied down" by love or family.

And in the end, that's what it comes down to: of the two films in question, Guardians of The Galaxy Vol. 2 not only builds off a - tangibly and conceptually - much bigger science fiction "idea" (a planet that's also a gigantic living organism that's also the embodiment of an abstract psychological/emotional concept); it's willing to explore it more fully and never loses sight of the human dimension that makes it all worth exploring in the first place. That's the real difference between science-fiction that "matters" beyond the whiz-bang trappings of the genre, not how serious your aesthetic insists upon itself but how much your meaning resonates in the space between idea and meaning.

Both films climax with the respective heroes wrestling with figurative gods and monsters... only one tells us why we should care why, or what the outcome is.