There is little doubt that HBO’s Game of Thrones is a remarkably faithful adaptation of George R.R. Martin’s sprawling, 5,000-page-long (and counting!) Song of Ice and Fire book series – perhaps one of the most faithful in the history of the medium.

However, as with any adaptation, there is a significant amount of deviation, if only as a product of transferring the written word to the visual realm. And while there are a number of general ways that showrunners David Benioff and Dan Weiss have managed to navigate the source novels to the small screen, such as trimming down the amount of dialogue per scene or condensing the sheer number of characters (one enterprising reader recently counted all the characters who are explicitly named in A Song of Ice and Fire and came up with over one thousand), there are actually a bevy of more specific tactics that the executive producers have employed. Each of these is worth analyzing, as it not only serves as a wonderful road map for how future showrunners may be able to successfully bring literary works to the small screen, but it also reveals the specific storytelling directives Weiss and Benioff have prioritized in their telling of Martin’s tall tale.

Here, then, are the 10 Biggest Changes from Book to TV.

(Concerned about spoilers, even though the series has now caught up to the books? Don’t be! We’ll be exploring the material from the first five seasons only.)

there are fewer characters

This has easily been one of the most frequently-employed tactics that the showrunners have found themselves returning to time and again. And it’s incredibly easy to see why: with a cast that currently numbers 27, plus a whole score of secondary characters, the show is already pushing the limit of the television-viewing audience’s endurance. And that’s not to mention the budgetary concerns behind thinning the cast down – each speaking role needs, of course, to be paid, and with actors’ salaries already increasing on an annual basis, keeping as many eggs in one basket as possible is in the producers’ best interests.

The effects of such a move have been negligible at worst and surprisingly productive, at best. When it came time for Tyrion Lannister (Peter Dinklage) to become the acting Hand of the King, for example, the showrunners decided against introducing Ser Jacelyn Bywater as the Imp’s choice for commander of the City Watch and instead opted to use the charismatic sellsword Bronn (Jerome Flynn), thereby keeping the entertaining banter between the two alive and crackling. Gendry (Joe Dempsie), who had already been introduced as King Robert Baratheon’s (Mark Addy) bastard, became Lady Melisandre’s (Carice van Houten) royal offspring of choice for sacrifice instead of the barely-in-the-novels-anyway Edric Storm.

The one exception to this rule so far? The infamous replacement of Sansa Stark (Sophie Turner) as Ramsay Bolton’s (Iwan Rheon) bride in Winterfell this past season, becoming a plaything for him to rape and torture. But she didn’t have it half as bad as her literary counterpart, Jeyne Poole, Sansa’s long-lost childhood friend. Sansa’s lack of agency in this narrative thread is still, some three months later, being hotly debated amongst all walks of the fandom.

a less developed Dorne

In a series that does so many things well, there are bound to be a few things that slip through the cracks and fail to deliver. The entire kingdom of Dorne, a fan-favorite in the Ice and Fire community, is that complete and total misstep from season five.

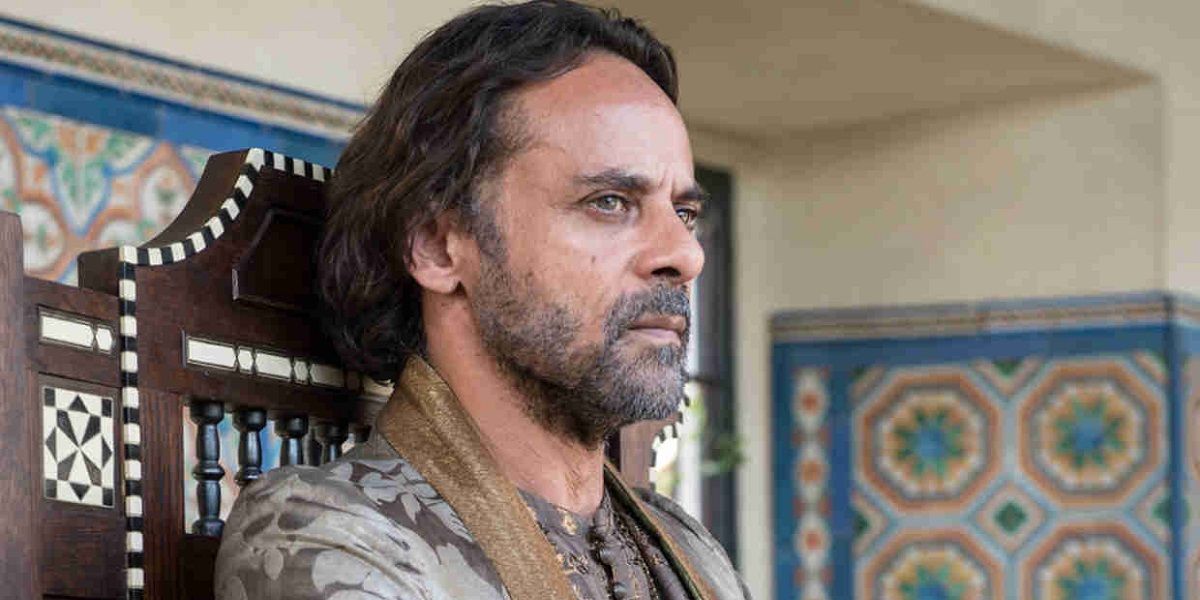

It’s instructive to see why this was the case. On paper, the alterations and simplifications employed seem like all the others that pop up in all the other aspects of Game of Thrones’s narrative (such as the aforementioned slimming down of the cast of characters to a more manageable number). Both of Prince Doran Martell’s (Alexander Siddig) children, Arianne and Quentyn – who are tangential-yet-important figures on Martin’s world stage – were cut, with Arianne's conspiracy of crowning Myrcella Baratheon (Nell Tiger Free) given over to Ellaria Sand (Indira Varma) and transformed into a plan to assassinate the young princess. In contrast, the eight Sand Snakes – daughters of Prince Oberyn Martell (Pedro Pascal) by several different mothers – are only periphery characters, who function almost exclusively in the background. Cutting their numbers in half and making them the main vehicle of the Dornish storyline seemed only natural, particularly given their pre-existent connection to Ellaria – less introductions, less expositions, more screen time for character and plot development.

Except, in execution, there is no development of any real kind in the southernmost kingdom, thanks chiefly to that other perennial problem of visual adaptation, lack of time. Furthermore, what time is spent with the characters is chiefly given over to poorly choreographed fight sequences and a few bizarre sex scenes.

less Extreme characterizations

Tyrion Lannister, in Martin’s rendition, is an incredibly sympathetic character, but he’s not necessarily an endearing one; he has people murdered if they pose a threat, he slips his sister drugs in order to temporarily incapacitate her, and even falls in love with a prostitute that obviously has no interest in him and cares only for the gold and jewels that his family name can afford her (a very different Shae [Sibell Kekilli] than what is seen on the show). He is, in short, the very embodiment of a grey character.

Cersei Lannister (Lena Headey) is similarly more ruthless and vicious in the novels, and not least because audiences have access to her inner thoughts, which reveal a rather bleak, arrogant, and brutal worldview. She gains weight as the story progresses, in no small part due to her ever-increasing alcoholism; she sleeps with men to have them do her bidding, whether it be spying on her brother, killing her husband, or falsely accusing her rivals of various crimes; and she is the one responsible for the murder of King Robert’s two dozen bastard children, as well as the attempt on Tyrion’s life during the Battle of the Blackwater (both of which were given over to her son, King Joffrey Baratheon [Jack Gleeson], by the showrunners). It’s safe to say that she’s a profoundly different character on the page than what she is on the screen.

Why the changes? There may not be much room for such nuanced explorations of these characters in a television series, but it’s also undoubtedly the result of Benioff and Weiss hoping to make their leads more relatable.

more dead bodies

George R.R. Martin has (deservedly) become famous for killing off a number of his characters across these past 19 years and five novels, but, it turns out, he’s got very little on Dan Weiss and David Benioff.

From King Stannis Baratheon (Stephen Dillane) and his haphazard family to Ser Barristan the Bold (Ian McElhinney), the lord commander of Daenerys Targaryen’s (Emilia Clarke) Queensguard, to Mago (Ivailo Dimitrov), a rider in Khal Drogo’s (Jason Mamoa) former khalasar, the showrunners have offed a surprising number of characters that have, to this day, managed to defiantly say “not today” to the god of death within Martin's novels.

This seems to be done in an effort to tie up various narrative strands much sooner than the glacial pace that Martin takes in his version of the story; Barristan, for example, is killed in order to replace him with Tyrion as Dany’s chief counselor and the ruler of Meereen in her absence (a major deviation from the source material), while Mago was offed to further strengthen Drago’s status as an accomplished warlord.

Of course, this constant stream of deaths makes for a more interesting discussion around the water cooler on Monday morning, which doesn't hurt either.

less ethnic diversity

While the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros are a rather pale place even in the books – a consequence of the story being so heavily influenced by medieval England’s Wars of the Roses – there is a small-but-deep-rooted strain of ethnic diversity lurking in the background. This has been significantly stripped away by the executive producers of Game of Thrones, as they stick mostly with white actors, even for those characters, like the Dornish or the Dothraki, who are meant to have olive or dark skin.

Interestingly, Weiss and Benioff have also “whitewashed” the various cultures that make up the large landmass of Essos (where both the Dothraki and Meereen are located), removing the extraordinarily colorful decorations of its denizens and sailing vessels, and smoothing out some of the eccentricities of their speech. Daario Naharis (Michiel Huisman), Dany’s warrior lover, is perhaps the best example of this: on the page, his hair and three-pronged beard are dyed blue, his mustachios and one of his teeth are gold, and he dresses in extremely loud garments. Despite the historical accuracy of some of these descriptions – the Swiss Guard, the protectors of the Vatican to this day, mostly fit this colorful bill – the showrunners probably feared that the exoticness of the Essosi might undermine the show’s gritty “realism.”

Though not (consciously) linked, these two factors work together to create a more homogenous version of Martin’s world.

not as many prophecies

There is a surprising amount of prophecy in the world of the Seven Kingdoms, and a great deal of it ends up influencing A Song of Ice and Fire’s cast in ways both big and small; Cersei, for instance, is haunted by the prediction that her brother will end up murdering her (but which one?), while Rhaegar Targaryen, son of the Mad King and brother to Daenerys, believed to his dying day that either he or his children would become the Prince That Was Promised, a legendary figure who was destined to save the world from the icy embrace of the White Walkers.

The biggest omission on this front, however, has to be the House of the Undying – situated in the legendary city of Qarth – which greets Daenerys with many a vision from both the past and the (possible) future. The prophecies hint at everything from King Robb Stark’s (Richard Madden) death at the infamous Red Wedding to the fact that Daenerys will be betrayed two more times in her lifetime, and all do a great deal to inform the arc of the characters and the overall story both.

Such a sweeping cut ends up being surprisingly ambivalent. On the one hand, its effects are minimal – Cersei still blames Tyrion for killing her son, and Daenerys still feels betrayed by Mormont – while, on the other, much of the backstory and texture that makes Westeros such a dizzyingly complex place is left to the ether.

there's more sex!

It may be hard to believe, given just how much time George Martin devotes to depicting his characters’ various sexual exploits, but the showrunners actually manage to up the sex quotient – by so much, in fact, that “sexposition” has now seeped into the vernacular, describing, say, Lord Petyr Baelish’s (Aiden Gillen) lengthy expository monologue while he watches two prostitutes audition for his brothel.

But the real standout here is the hugely controversial choice of having Jaime Lannister (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau), upon his arrival back in King’s Landing, force himself on his sister. Why there is such a change from the source material, in which their incest is consensual, is still inexplicable – save for the overriding desire to titillate and shock the audience, seemingly no matter the cost. (It’s one of the few – if not the only – time that the showrunners opted to make their central protagonists look bad, as discussed previously.)

motivations are less complex

This alteration seems, on first blush, a no-brainer, the logical extension of the executive producers’ twin desires of bleaching their leads of most of their nastier imperfections and of simplifying the convoluted, overarching narrative as much as humanly possible. And while that may be so, it still leaves a considerable question in its wake.

The practice in question is streamlining the sometimes quite tangled motivations the characters have for making some of their most iconic decisions. Tyrion, for instance, is only moved to kill his father once he learns from Jaime that Tysha, his first wife, was simply a common girl and not the prostitute that his father claimed she was. Another example: the brothers of the Night’s Watch only initiate their assassination plan against Lord Commander Jon Snow after he boldly proclaims that he is going to temporarily set his vows aside and ride to war against Ramsay Bolton, for the (supposed) death of King Stannis Baratheon and the torture of his sister/Ramsay’s new bride.

Is Tyrion sufficiently motivated to commit fratricide? Are the crows of the Watch too two-dimensional in the series? A certain amount of context is perhaps routinely being lost to expositional efficiency, and it may be a practice that will cause problems as the series barrels towards the final chapter of the story.

the narrative is less complicated

When Arya Stark finds herself a prisoner of the Lannisters at Harrenhal, the castle to end all castles, she manages to quickly land in the (relatively) safe position of cupbearer to Lord Tywin Lannister (Charles Dance). After he departs with his men, she manages to escape, heading back out on the road home (or, at least, so she hopes).

That’s a remarkably straightforward storyline, probably because it didn't exist in the Ice and Fire novels.

In Martin’s telling, Arya manages to land herself right in the middle of a surreptitious plot of House Stark loyalists attempting to wrestle control of the castle away from the Lannisters. In the middle of the action is the Brave Companions – better known as the Bloody Mummers to the rest of the Westerosi – a motley crew of mercenaries standing in the center of the carnage that descends upon the castle. To cover this in the television show would’ve easily required a dozen more characters, one big action scene, and (literally) three or four more episodes.

It’s only one example, but it’s an extremely representative one – boil a story arc to its naked essence, find a way to communicate its bare necessities to the audience, and then reconstruct it in a much more visually adaptive way. In this fashion, the core of Martin’s story has been told in only approximately half the time that the author himself has taken – a rather positive development, given the increasingly bloated page counts of his books.

there's more blood and guts

Just as the showrunners have attempted to expand the depth of the sexual material in their television series, they have displayed a stubbornly consistent desire to maximize the action – along with the romance and humor – for similar reasons.

Of the large swaths of new storylines created to tread water while the other plots catch up (Dany attempting to find her stolen dragons in Qarth) or tell a more heroic story (Jon Snow leading the charge to get vengeance against those mutineers who killed Lord Commander Jeor Mormont) or a more overtly romantic one (Robb’s falling in love with the beautiful-but-incredibly-modern Talisa Maegyr), most of them have fared rather poorly either in terms of their execution or in comparison to Martin’s own material. And it’s easy to see why – whereas Martin spends the vast majority of his time in an attempt to steer his narrative away from the more obvious tropes or clichés, Benioff and Weiss expend a great deal of energy doing the opposite. (Which is not to say that the two exec producers are bad writers by any stretch of the imagination –but to say that the temptation toward cliché is even greater on the TV screen.)

It’ll be interesting to note whether Weiss and Benioff have been made sufficiently aware of this inconsistency, and whether they’ll be able to compensate for it; now that they have run out of material to mine from the published novels.

-

Have you discovered other, more revealing choices that David Benioff and Dan Weiss have been employing over the past five years? Did we miss a giant – or controversial – deviation from George R.R. Martin's series of books? Be sure to spell it all out in the comments below.