Warning: SPOILERS ahead for Dracula.

Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss tried to replicate their Sherlock magic with Bram Stoker’s Dracula, but the end result is highly disappointing. The 1897 novel Dracula, written by Irish author Bram Stoker, is one of the most influential stories ever written, as well as one of the most adapted books in pop culture history. The story of a Transylvanian vampire and his quest to take over London has delighted and thrilled readers for over 120 years.

Countless films, TV shows, books, and assorted media forms have taken Dracula as their primary source and the Count himself remains one of the true idols of the 19th and 20th centuries. It's not hard to see why Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss would want to put their own spin on Dracula; after all, they did so with another one of pop culture's undisputed icons, Sherlock Holmes, and created a minor fandom phenomenon as well as helping to make a star out of Benedict Cumberbatch. Sherlock, however, ended on a real low point that left many of the series’ more zealous fans with a bad taste in their mouth.

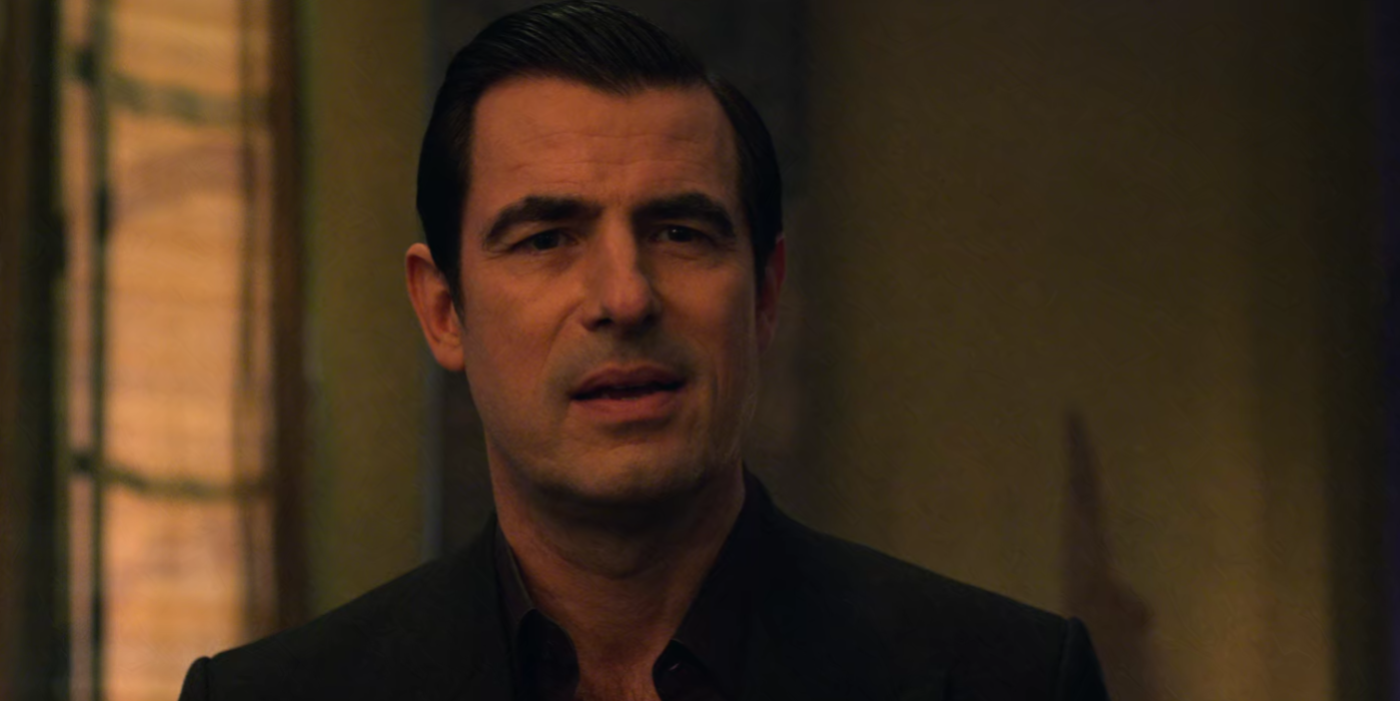

Dracula stars Danish actor Claes Bang as the Count and took heavy liberties with the source material. This is pretty common for Dracula adaptations – indeed, few of them ever stick to the book, preferring instead to use its characters and plot points freely to tackle contemporary ideas and concerns – and par for the course for Moffat, who previously offered fans a reinterpretation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. In many ways, Dracula exemplifies the myriad problems that fans have with Moffat’s style and themes and how he tends to fall into the same holes with each story he takes on. For any fan who grew weary of his run on Doctor Who or felt let down by the way Sherlock wrapped up, the issues with Dracula will feel all too familiar.

The Modern-Day Twist was a Bad Idea

At the end of the second episode, Dracula awakens from his underwater slumber and crawls onto the beach at Whitby, only to find that he's been sleeping for 123 years and has woken up in 2020. Moving Sherlock to the current era was a relatively lateral move where the modernized elements have context but with Dracula, the sudden change to fish-out-of-water comedy fell seriously flat. Many a time travel story has done the trope of having the person or creature from a past era be baffled and amused by modern technology, which often feels like a cheap excuse for bad jokes. Dracula suffers this same fate, and there's something just not fun or interesting about seeing this devastatingly dangerous creature of the night take selfies or get excited about a fridge.

Dracula was at its best as a period piece, allowing Moffat and Gatiss to languish in the gorgeous gothic settings and Hammer Horror inspired mood. They couldn’t replicate that tone with the modern setting and they also didn’t seem to have a reason to do so beyond the gimmick. The twist didn’t add anything new or unique to its narrative, which was already seriously lacking in ideas. The only amusement or intrigue that comes from the set-up is the novelty of seeing Dracula swiping for his next meal on Tinder, and even then, other Dracula movies have done this set-up far better, such as Dracula A.D. 1972.

Lack of Character Development and the Treatment of Lucy

The lion’s share of Dracula’s focus falls on the character of Sister Agatha (played by Dolly Wells), then her great-great niece in the modern-day episode, Zoe (also played by Wells). She is revealed to be a Van Helsing and is this story’s version of the Dutch doctor who helps to bring down Dracula. She’s not a bad character, although she often feels like a full house bingo card of Moffat’s worst habits when it comes to writing women. The issue with her is that she takes up so much of the three episodes’ spotlight that the other characters, both new and from the original book, cannot help but suffer as a result.

Mina Murray, the fiancée of Jonathan Harker, is reduced to a mostly silent figure who does little but cry and make one especially stupid decision at the end of the first and only episode she really appears in. Given how crucial Mina is to the novel and how striking a female character she is to this day on the page, the adaptation proved particularly disappointing here. Jonathan fares better (or far worse, in terms of his fate), but the build-up the episode gives us in showing the trauma he deals with is quickly dismissed in the second episode. The modern-day characters are little more than stock players who would seem more at home in Hollyoaks or Riverdale than Dracula. Jack Seward is now a medical student who mostly pouts. Quincey has a handful of lines and no impact on the plot. Renfield fares better as he is given the episode’s most entertaining (if nonsensical) twist as Dracula’s lawyer. The one who suffers the most, sadly, is Lucy Westenra.

Lucy is the character who tends to get the short end of the stick in most Dracula adaptations. In the book, she is a wholesome, if somewhat naïve, young woman with three romantic suitors looking to marry her. Her immense capacity for love makes her a symbol of sweetness and purity - the kind that Dracula so eagerly wants to corrupt. She even says that she wishes she could marry all three men so that none of them would have to feel rejected. This is not greed or promiscuity on her part: It’s a genuine display of affection. Sadly, most adaptations turn that into Lucy being an uninhibited man-eater who loves to chase and manipulate the poor gormless boys who follow her around. At best, it’s lazy writing. At worst, it’s slut-shaming.

Moffat and Gatiss try to hang a hat on this criticism by having their Lucy directly call out slut-shaming, but that doesn’t negate how they spend the entirety of her arc framing her as sexually flighty and uninterested in the feelings of her romantic partners. She is framed explicitly as wantonly sexual as well as deeply obsessed with her own beauty. This Dracula adaptation has Lucy willingly offer herself to the vampire rather than be his traumatized victim, but her fate remains wholly cruel. After being killed by Dracula, she must wait to arise from the dead and be with him, but she didn’t count on her family organizing a cremation over burial, so when she turns up at Dracula’s home after her funeral, she is charred beyond recognition. At first, she sees herself as still beautiful and gazes smugly at her warped reflection, but once she sees what she has become, she immediately wants to die (which Jack Seward helps to happen). The implication here is that Lucy’s sin was her own vanity and that her nasty fate was more than worthy of her stupid decisions. This was a staggeringly sexist ending and one that felt all too at home in the history of Dracula adaptations that would rather make Lucy a silly slutty girl than a complex woman of love and desire.

Dracula’s Endless Queerbaiting

Before Dracula aired, Steven Moffat made a comment about how Dracula was not bisexual but “bi-homicidal” in an attempt to get ahead of any fandom conversations that would inevitably surround the series. Sherlock was especially popular with fan fiction writers and shippers, in large part because the show frequently leaned into the queer subtext. With Dracula, it couldn’t help but feel like a “no homo” disclaimer, and fans felt all the more irritated by the comment when, within the first five minutes of the first episode, a character forwardly asked Jonathan Harker if he’d had sex with Dracula. Dracula also refers to Jonathan as his “bride” and every moment of contact he makes with a victim, regardless of gender, is shown in a deeply sexual manner. The implication is clear with how Dracula devours humans and what a pleasurable experience it is meant to be for him. Moffat may be eager to let the audience know how not gay Dracula is, but he sure is happy about milking those moments of queer subtext for all their worth.

The Ending is Terrible

Steven Moffat loves to build up big ideas and promise lavish climaxes with complicated, near-labyrinthine plotting. The only issue is that he seldom knows how to achieve such a payoff, or he gets bored with his own ideas and simply doesn’t bother. This is most evident in Sherlock, when the series set up a massive mystery over how Sherlock survived the fall that supposedly killed him, then seemed to chastise its own audience for caring about the solution they were promised while never delivering one. Dracula doesn’t quite go that far, but it does hint at greater drama where it cannot provide any.

Much is made of Dracula’s mysterious origins and why he suffers from the ailments that plague vampires: The allergy to sunlight, the fear of the cross, and the inability to enter a room uninvited. The show keeps promising an answer to these issues (although plenty of Dracula adaptations don’t and are better for it) and offers a few red herrings that would have been highly satisfying. Instead, the answer is a big thematic and emotional let-down that provides no drama or satisfaction to the viewer, and the series concludes on a bum note as a result. Once again, Moffat lured in audiences with big promises then discarded them at the last minute.

There are other issues with Dracula that we could list for days if necessary: The various dropped plot threads and abandoned characters, like Renfield; the rushed nature of the entire third episode; the lack of real thematic development. What proves the most disheartening about this series is how all its problems are the same ones that are found in everything else Moffat has done. The failings here are near identical to the ones that made Sherlock, Jekyll, and his run on Doctor Who suffer. It’s especially disheartening because Moffat’s work can often be deeply entertaining and witty when he commits to an idea and doesn’t overcomplicate the plot. Instead, Dracula feels like another example of what happens when a showrunner with major weaknesses is let off the leash with no accountability.