As one of the first tabletop roleplaying games, Dungeons & Dragons wound up not only making a lot of foundational fantasy content, but also creating wildly new things like Planescape and Spelljammer. D&D codified many elements of the "standard fantasy setting" seen in both western and eastern RPGs – medieval societies, dungeons filled with monsters and treasures, thieves guilds, Tolkien-esque elves and dwarves, and so on. At the same time, many of the official settings of D&D bend or outright break the traditional tropes of modern fantasy fiction, none more so than Planescape. This multidimensional campaign setting, centered around a city called Sigil that lies at the center of D&D's multiverse, eschews classic dungeon-crawling gameplay and good god vs. evil god narratives in favor of reality-warping phenomena, journeys between different cosmic planes, and city factions fighting over different creeds of existential philosophy.

1999's cult classic Planescape: Torment was a weirder kind of RPG, built off the same Infinity game engine as the Baldur's Gate series, is both an excellent computer game and an excellent example of how weird and thought-provoking a D&D tabletop game in the Planescape setting can get. The player character of Planescape: Torment, a nameless amnesiac covered with scars and tattoos gained over the course of an immortal life, embarks on a journey through Sigil, the City of Doors, to discover his forgotten past. His potential companions include a talking skull, a succubus who became a chaste cleric, a cubical machine drone gone rogue from his mechanical society, and a suit of armor possessed by an insanely zealous spirit of justice. The various side-quests in this game include building a D&D wizard's spellbook out of street vendor trash, helping a pregnant alleyway give birth, and debating a solipsist into believing they don't exist (which causes them to vanish from reality). Finally, the overarching theme of the game is not centered around the clash between good and evil, but the more poignant philosophical riddle, "what can change the nature of a person?"

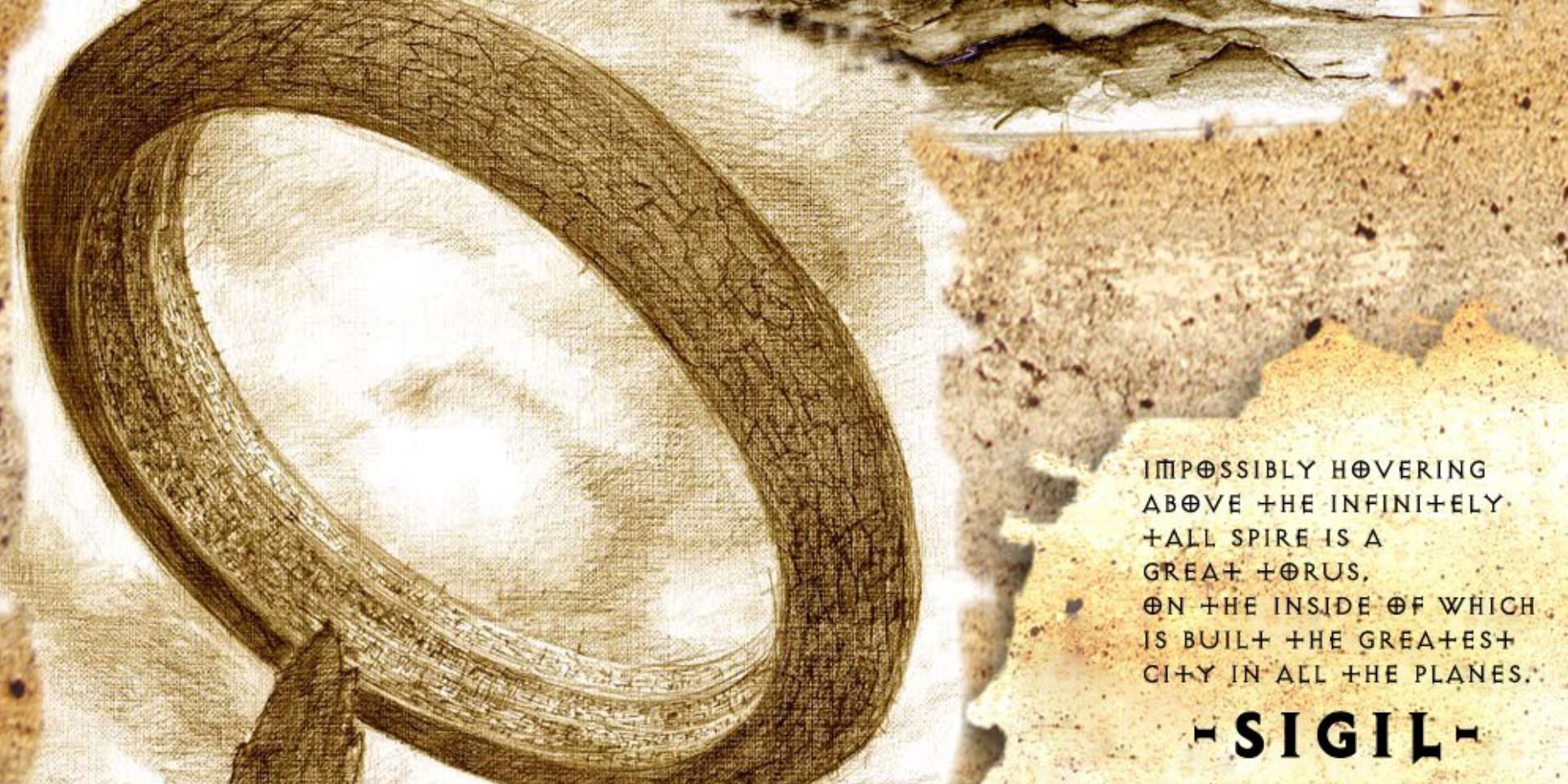

The first official Planescape source book was first published in 1994 for Dungeons & Dragons 2nd edition, drawing on the moral alignment rules, monsters, and "Great Wheel" cosmos metaphysics established in previous D&D settings like Spelljammer and Dark Sun to create a setting that would let player characters go on journey to Heaven, Hell, and every plane in-between, then return to the city of Sigil, a ringed, gravity-defying metropolis at the center of the Dungeons & Dragons multiverse. Even by D&D's flexible standards, the setting of Planescape is particularly weird and genre-defying for the following reasons.

D&D's Planescape Setting Has Mind-Bending Existential Themes

Gods cannot step foot in Sigil, the City of Doors. Any gods or god-servants who try to circumvent this arcane ban are gruesomely butchered by the mysterious Lady of Pain, the mysterious ruler of Sigil whose metal face is the main logo of the Planescape D&D campaign setting. Anyone who tries to worship the Lady of Pain as a goddess or endangers the integrity of Sigil is torn apart by her unseen blades or hurled into labyrinths from which escape is nearly impossible.

Besides being a weird and eerie piece of game lore, the Lady of Pain's rule over Sigil cause the divine pantheons and religious faiths seen in other D&D settings to be largely absent or distant in a Planescape campaign. In the place of religious institutions, monarchies, or mercantile republics, players in a Planescape game session can instead join or contend with one of the many factions who administer the city of Sigil, each built around a certain philosophical creed.

Factions like the Doomguard or Dustmen (similar to certain bleak faiths in Pillars of Eternity or the upcoming Avowed) see life and existence as a prison of suffering, seeking either to destroy the multiverse itself or achieve a state of final death that will keep them from reincarnating or moving on to the afterlife. The terrifying Mercykillers uphold a creed of punishing criminals for their crimes, regardless of their motivations of circumstances, while the gentle Bleak Cabal believe the universe is meaningless chaos and seek to do good for others regardless. By centering storylines in the Planescape setting around the philosophical themes mentioned above, players of a D&D campaign set in Sigil wind up experiencing very existential stories about introspection, ethics and the search for meaning and self-worth.

D&D's Planescape Setting Helped Break Old Character Creation Restrictions

Older versions of Dungeons & Dragons such as D&D 3.5 Edition were much more restrictive when it came the character creation process. Certain character classes like Paladin and Druid could only be held by characters with a specific moral alignment (Lawful Good, Lawful Neutral, etc.) while race options like Elves and Dwarves would bar players from taking class options or upgrading a character attribute beyond a certain point. Finally, certain non-human species such as bugbears, demons, or dark elves (before Drizzt Do'urden became a popular character in the Forgotten Realms setting) were locked into a specific viewpoint of Evil, Good, Chaos, Law, or neutrality, unable to evolve their worldviews beyond a certain perspective.

Being a metropolis with doors leading to every possible reality, the city of Sigil, primary locale of Planescape, is full of immigrants and monsters from the D&D multiverse – demons, devils, celestials and creatures even odder working, living, and even falling in love with members of the more conventional species taxonomy of D&D games. As a consequence of this worldbuilding, Planescape wound up popularizing novel D&D race options such as tieflings (children or descendants of humans and devils), aasimir (children or descendants of humans and angels), and githzerai (psionic humanoids who dwell in cities that float through the chaotic plane of Limbo).

On a narrative level, the worldbuilding of the Planescape books encouraged Dungeon Masters to shed traditional power/alignments restrictions on player races and "monsters," making it possible to create unique, non-optimized D&D characters such as virtuous devils or freedom-loving Modrons. In the long-run, Planescape's more freeform attitude towards PC and NPC creation established precedent for both players and developers to ditch old restrictions on character classes and moral alignments, adding diversity to the cast of a D&D game and shedding the unfortunate racial essentialism of old D&D rules.

It's probably not a coincidence that the newest edition of D&D, which removes starting stat restrictions for D&D races, was announced around the same time as news of the upcoming 5th edition Planescape sourcebook. Exactly what wonders will await players as they venture back into one of Dungeons & Dragons' most mysterious and intriguing settings is impossible to say, but it's sure to be a wild and worthwhile ride.