The HBO documentary Crazy, Not Insane explores serial killer psychology and thematically contrasts with reductive tropes from movies and television. Directed by Alex Gibney, the true crime production focuses primarily on the career of Dorothy Otnow Lewis, an American psychiatrist whose groundbreaking research methods in the 1980s forever changed the general perception of serial killer behavior.

Unfortunately for Lewis, her techniques were dismissed by professional colleagues during the '80s and beyond, even though she had extensively researched and interviewed real-life murderers. In Crazy, Not Insane, the subject emphasizes the importance of understanding how brain dysfunction and childhood abuse affects the behavior of all humans, certainly those who eventually kill later on. Lewis also discusses the lasting effects of brain trauma, most notably how it can trigger abnormal electric activity in the limbic system. Much of Crazy, Not Insane on HBO features Lewis recalling her experiences with infamous serial killers and how she came to realize that Dissociative Identity Disorder, otherwise known as Multi-Personality Disorder, is prominent amongst murderers who subconsciously found ways to protect themselves from perceived threats. The documentary shows what Lewis has endured because of her unorthodox methods, but also implies that some subjects may have created personas during the interview process.

Crazy, Not Insane begins by acknowledging the most common depiction of serial killers in movies and television: hateful people who kill for one specific reason, and one reason only. Lewis speaks about murderer Joseph Paul Franklin - a white supremacist who went on a killing spree from 1977 to 1980 - and she establishes the tone for the documentary by recalling her mother's belief that "bigotry and insanity are different." During the '70 and '80s - a time when the FBI Behavioral Science Unit was only beginning to understand the motivations of serial killers (see Mindhunter), mainstream movies and television often depicted such figures as wild-eyed maniacs who murdered solely to watch someone suffer. In short, killers were conveniently labeled as being "insane" because of their actions, when in fact - as Lewis argues - it's the full life story that matters most when analyzing their behavior.

The religious concept of "evil" is another trope from movies and television that doesn't fully account for brain trauma, childhood abuse, and societal factors that trigger certain individuals. In Crazy, Not Insane, a fascinating TV clip shows Lewis speaking with conservative host Bill O'Reilly, who suggests that anyone who kills is "evil." In response, Lewis points out that "evil" is a "religious" concept and not a "scientific" concept, and that psychological evaluations are indeed quite important when trying to understand the motivations of murderers. Over the decades, serial killers in movies and television tend to receive messages from higher beings, which thematically reinforces the "insane" concept. This trope undoubtedly stems from an infamous '70s serial killer like David Berkowitz, aka the "Son of Sam," who claimed that his neighbor's dog was possessed by a demon and forced him to kill. In 1979, the serial killer admitted (via The New York Times) that his story was a hoax, but pop culture took the concept and ran. After all, the term "serial killer" wasn't actually used in print until 1981 as a label for convicted Atlanta murderer Wayne Williams.

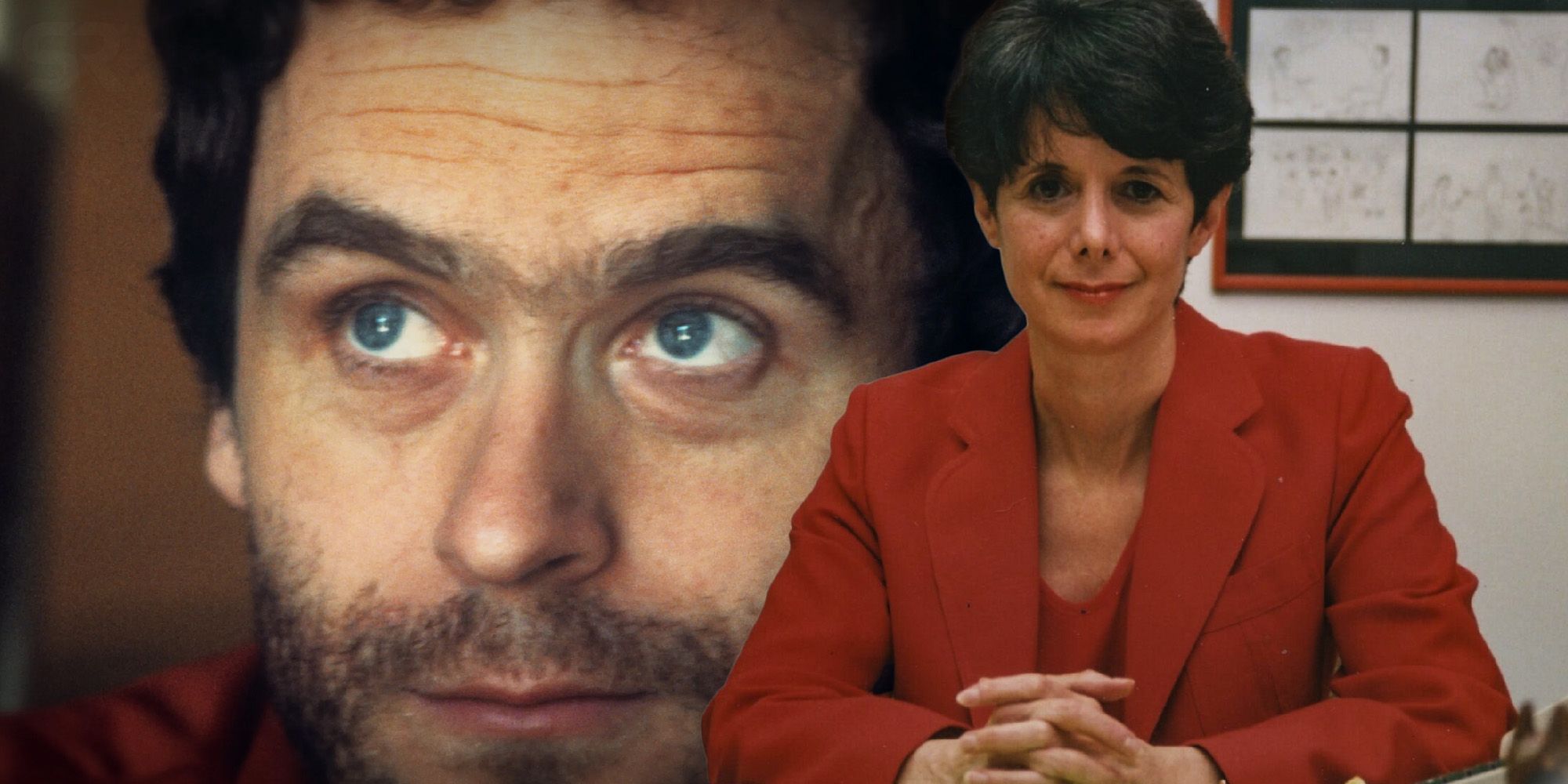

In movies and television, serial killers are often portrayed as individuals who take pleasure in manipulating others while discussing their crimes. While that may indeed be true in many cases, a late sequence in Crazy, Not Insane on HBO suggests that it's often because the murderers don't understand themselves. Lewis recalls speaking with Ted Bundy, who requested her presence just one day before his execution, apparently because the psychiatrist was the one person who understood him the most. Bundy refused to acknowledge that his childhood was anything other than splendid, but Lewis reveals that he admitted to having a sexual encounter with his sister (which led him to target women who looked like her), and the psychiatrist also heavily implies that Bundy was born out of an incestuous relationship between his mother and grandfather. In true crime documentaries, though, filmmakers tend to spend more time on Ted Bundy's charisma and public persona rather than his complex upbringing.