Remaking a classic film is like putting your child up for adoption. You should only do it if you’re sorely in need of cash, and even then it’s a tragedy. We hope that the sarcasm here is self-evident, as is the modern studios’ greed when it comes to sacrificing our cinematic memories in favor of the almighty dollar.

Would you spit on a Van Gogh? Edit Faulkner? Tame Tchaikovsky? If your answer is anything but a resounding "NO," then pray for forgiveness. Remember: making the subtlest changes to Yoda’s skin tone in the re-mastered Star Wars collection made George Lucas a pariah, so let this be a warning to Hollywood: you remain relevant and essential to culture and politics because of your creativity. Continue to mine that resource and resist the temptation to retread hallowed ground. It’s in your best interest to leave the true gems of cinematic history to the Criterion Collection, The Smithsonian and the U.S. National Film Registry

We already covered 10 Movies Hollywood Will Inevitably Remake, but here is our list of the 10 Movies Hollywood Should Never Remake:

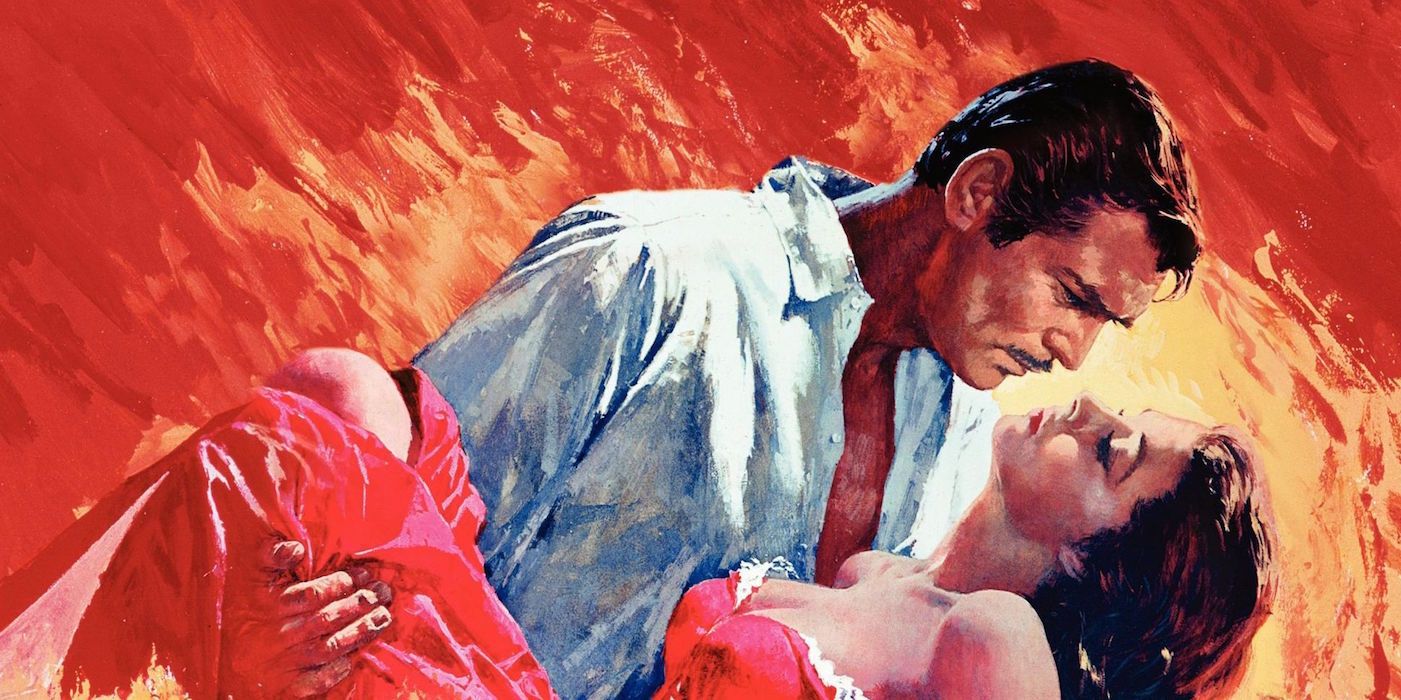

Gone With the Wind (1936)

Adapting Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel required a level of dedication and grandiosity that Hollywood had never experienced. In many ways, Victor Fleming’s Gone With the Wind became the gold standard for the film epic. Leaving no stone unturned with its sweeping vision of the antebellum south in its first half, and the utter destruction of America’s infighting and the attempts at reconstruction in the second, the 1939 film leaves an impression that is hard to shake.

Vivien Leigh, Clark Gable and Hattie McDaniel delivered some of the most memorable performances of their time, filling the screen with stark contrasts of mercurial emotion, old-time masculinity and ironic humor. Accompanied by Max Steiner’s groundswell of a score, Gone With the Wind fired on all cylinders. Could it be remade today? In name only.

Casablanca (1942)

Three years after the success of Gone With the Wind, the Hollywood studio system chugged along with its mercantile output of films. They had a formula that worked. When Casablanca came down the pike as an adaptation of the unproduced play, Everybody Comes to Rick’s, it was put in the production fast lane to capture the zeitgeist of WWII during the Allied invasion of North Africa.

The release of the film proved brilliantly timed, and while Casablanca enjoyed great box office returns and a positive reaction from the press, it hooked into the public consciousness well after its initial debut. Thanks to a transcendent script that offers memorable lines for every scene in the film, director Michael Curtiz’s wartime drama remains one of the most distinctly romantic films ever created. Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman scorch the screen. The imagery, the music and the tone is almost dream-like, and every time you finish watching Casablanca, you want to play it again.

Citizen Kane (1941)

Orson Welles was a mere 26-years-old when he directed Citizen Kane, pouring a maturity and gravitas into the film that few directors have since matched. An ardent man of the theater, Welles spent his early 20s dedicated to the stage despite Hollywood’s financial advances. When his thespian endeavors left him in need of money, he flew out to Los Angeles and, after a tour of RKO studios, signed a two-picture deal with its executives.

Surely, Welles possessed social graces of the Clooney brand, as the first-time film director walked away with a hefty budget, unbridled screenwriting autonomy, and, the gold standard of directorial power, the rights to final cut in the editing room. In essence, the brilliant minds at RKO trusted this mid-20s artiste with the keys to the kingdom.

Often playing tricks on the studio and working around the clock, he made the movie exactly as he envisioned it. Not only is Citizen Kane a lasting icon of vintage Hollywood, it should be touted as evidence that great directors deserve complete creative control. If, for every ten aborted attempts at greatness, audiences get one Citizen Kane, then the "Dictator Director" gamble beats studio bureaucracy in the long run.

It’s A Wonderful Life (1946)

While it's often remembered as a Christmas movie, Frank Capra’s touching 1946 film is a heart wrenching drama in Santa-clad drag. Thoughts of suicide, of the kind that George Bailey (James Stewart) experiences, are no laughing matter. Perhaps that is why the best moments in the movie remind us that we indeed live a wonderful life.

It’s the kind of movie that makes you want to hug your family and slow things down for a minute. The despicable villain, Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), makes your skin crawl with his selfish cruelty, almost providing a call to action against out social tendency toward greediness.

It’s a Wonderful Life has its moments of horror, especially when George Bailey sees what life would be like without him. Capra directs those sequences with a nightmarish quality that haunts just as readily as the reconciliation scenes endear. Enough compliments cannot be given to Jimmy Stewart for this performance, and for that reason alone, the movie should remain completely untouchable.

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate!” So speaks the sadomasochistic Captain (Strother Martin) in Cool Hand Luke, illustrating exactly the difference between weak men of his ilk and the indomitable spirit of men like Lucas “Luke” Jackson (Paul Newman). Donn Pearce and Frank R. Pierson penned an airtight screenplay that offered Mr. Newman his tour de force performance on a silver platter.

Cool Hand Luke can never be reiterated because the film is defined by its lead actor. That brand of cocksure arrogance and deep seated depression made blue-eyed Newman something of a paradox. He pulled off that dramatic cocktail in The Hustler, just six years prior, and he perfected his craft in the time since. In the film, Newman plays a rabble-rousing Korean War vet who gets hooked onto a chain gang for drunkenly beheading parking meters.

Things look grim for Luke, but while he serves his sentence, he rediscovers his tenacity and, through a series of jail yard trials, becomes the most respected man in the prison. Unsurprisingly, Cool Hand Luke became one of the most respected films in history.

The Godfather (1972)

Whoever remakes the Francis Ford Coppola classic will surely be the antichrist. Any attempt to reimagine the Corleone epic would be a living insult to cinema, to Brando, Pacino, de Niro, Duvall, Cazale and the countless other artists that took Mario Puzo’s book and turned it into a piece of pure poetry.

How does one begin to describe the magnificence of the 1972 classic? The blind bard didn’t need to describe Helen of Troy much. She was just that perfect. The Godfather has reams of literature dedicated to it, and despite the film world’s nauseating dissection of the gangster epic, the conversations will never cease.

Themes of respect, honor and family run deep in Coppola’s trilogy, and while many of the Corleones have blood on their hands, they endeared themselves to audiences with their passion and fervor for life. The production values are transcendent, and the contrasts between characters like Michael and Sonny Corleone make for a truly sizzling film.

The Graduate (1967)

“Mrs. Robinson, you’re trying to seduce me. Aren’t you?” Mike Nichols fills his second-ever film with enough phallic references and imagery to warrant an R-rating, but his directorial cunning and class eked out a parent-friendly PG. The Graduate became the mainstay of Nichols and Dustin Hoffman’s careers, with that undercurrent of sexual restlessness and identity crises that encapsulated the era.

Sure, watching Benjamin Braddock (Hoffman) sleep with the eminently seductive Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft) proved controversial for the times, but it gave audiences one of the most humorous, engaging coming-of-age stories set to film. Taking place in the 1960s’ where the nuclear American family had far less fission than the atom bomb, Nichols’ wry jabs at the culture (“plastics”) was advanced, impeccable and inimitable.

On The Waterfront (1954)

On the Waterfront was based off a handful of articles published in 1949 that exposed the brutality and infighting amongst New Jersey longshoreman, making the film a once in a lifetime opportunity. Providing the ultimate source material for a film, journalist Malcolm Johnson gave director Elia Kazan the kind of raw goods and realism that he always strived to find.

Kazan was notorious for provoking fights and insecurities on his sets, lighting the fuse for what he hoped would be a powder keg explosion once the cameras started rolling. Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando in one of his most enduring roles) represents the all-American blue collar worker who had a shot at glory and missed, duped into degradation by his duplicitous mob-boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb, the ultimate onscreen menace).

Ultimately, the film shined a spotlight on the corruption imbedded in the Hoboken Docks and gave filmgoers a slice of life that can never be replicated.

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Peter O’Toole is a heavyweight in film lore, and though he somehow eluded the Academy’s favor and failed to win Best Actor for Lawrence of Arabia, his portrayal of T.E. Lawrence defined the Hollywood hero. Thin and educated with an English scholar’s enunciation, O’Toole transforms Lawrence into a brilliant cowboy of the Arabian sands.

David Lean’s 1962 epic portrays its eponymous character as a British hero who helped further the Union Jack’s success in the Arabian Peninsula during the first World War. A regular John Wayne he was not, however, and that’s where O’Toole found room for his first-rate acting chops. In the film (brilliantly shot by cinematographer Freddie Young), T.E. Lawrence is shown as a compunction-filled warrior, conflicted by his violent and peaceful vacillations. He wears his guilt ridden PTSD on his Bedouin-robed sleeves, but in classic English style, his own worries do not keep him from fulfilling his duty.

O’Toole’s Lawrence struggles with his responsibilities, but is never swallowed by them. Produced well after the release of Gone With the Wind, Lawrence of Arabia may justly be considered an extension of Victor Fleming’s epic, showing Hollywood the boundless potential of cinematic storytelling.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Remaking a Kubrick film would take incredible chutzpah. How would one begin to access the famous director’s painstakingly particular approach to filmmaking? Perhaps the most untouchable entry in his oeuvre is A Clockwork Orange, a true trip down mentally-unstable-lane that includes one of the most sadistic scenes ever set to the innocent “Singin’ in the Rain.” Poor Gene Kelly.

Alex (Malcolm McDowell) spearheads the Britain-bound gang of cockney youths that rapes and pillages its way through an increasingly broken society. It is an upsetting and shocking movie that assaults the eyes while throwing gut punches to our sense of morality and reason. If there is any image in the film that best captures Kubrick’s capabilities, it is undoubtedly the scene in which Alex has his eyes mechanically pried open and force fed assaultive imagery that rewires his brain.

Thanks, Stanley.

-

There you have it! What classic movies do you think should be exempt from a Hollywood remake? Let us know in the comments below!