Both the original Blade Runner and its sequel, Blade Runner 2049, are highly regarded nowadays, yet they both bombed at the box office. Released in 1982, the first Blade Runner brought director Ridley Scott and actor Harrison Ford together at a time when the pair were hot off the success of three of the most iconic sci-fi films ever (Alien, Star Wars (1977), and The Empire Strikes Strikes Back). Combined with revered source material (Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), the film has the makings of an instant-classic on paper. In motion, though, things played out differently and Blade Runner went on to flop commercially.

In the years that followed, however Blade Runner became a cult classic thanks to support from cinephiles and Scott releasing multiple different cuts of the film (some better-received than others). Upon acquiring the rights to the property in 2011, Alcon Entertainment thusly decided to move forward with a sequel, with Denis Villeneuve (then coming off his critically acclaimed dramatic thriller Prisoners) eventually taking over as director from Scott. Titled Blade Runner 2049, the movie picked up in real-time after the events of its predecessor, with Ryan Gosling playing a replicant Blade Runner named K and Ford reprising his role as Rick Deckard.

Much like its predecessor, Blade Runner 2049 had a dream team of talent involved, yet went on to bomb at the box office, killing Alcon's plans for additional sequels and potential spinoffs. In both cases, though, Blade Runner and its followup's problems began before they'd even premiered in theaters.

Blade Runner & 2049 Both Divided Critics

Upon its initial release in theaters, Blade Runner was fairly divisive among critics. Many reviews praised the film for its gorgeously haunting vision of a then-futuristic Los Angeles (not to mention, Vangelis' mesmerizing electronic score), but felt it suffered from sluggish pacing, thinly-drawn characters, and a storyline that's simply not all that interesting on the surface-level. Not helping matters, Blade Runner's original domestic theatrical cut included voiceover narration by Deckard that Ford infamously disliked (which explains why his recorded delivery is so often noticeably non-committal). The film's reputation improved as it was re-evaluated over the decades and Scott released his preferred cut(s) of the movie, further calling attention to its deeper sci-fi themes about identity and what it actually means to be human. To this day, though, there are still a lot of cinephiles that appreciate Blade Runner for its craftsmanship and place in history, yet find its impact on the sci-fi genre far more interesting than the actual film.

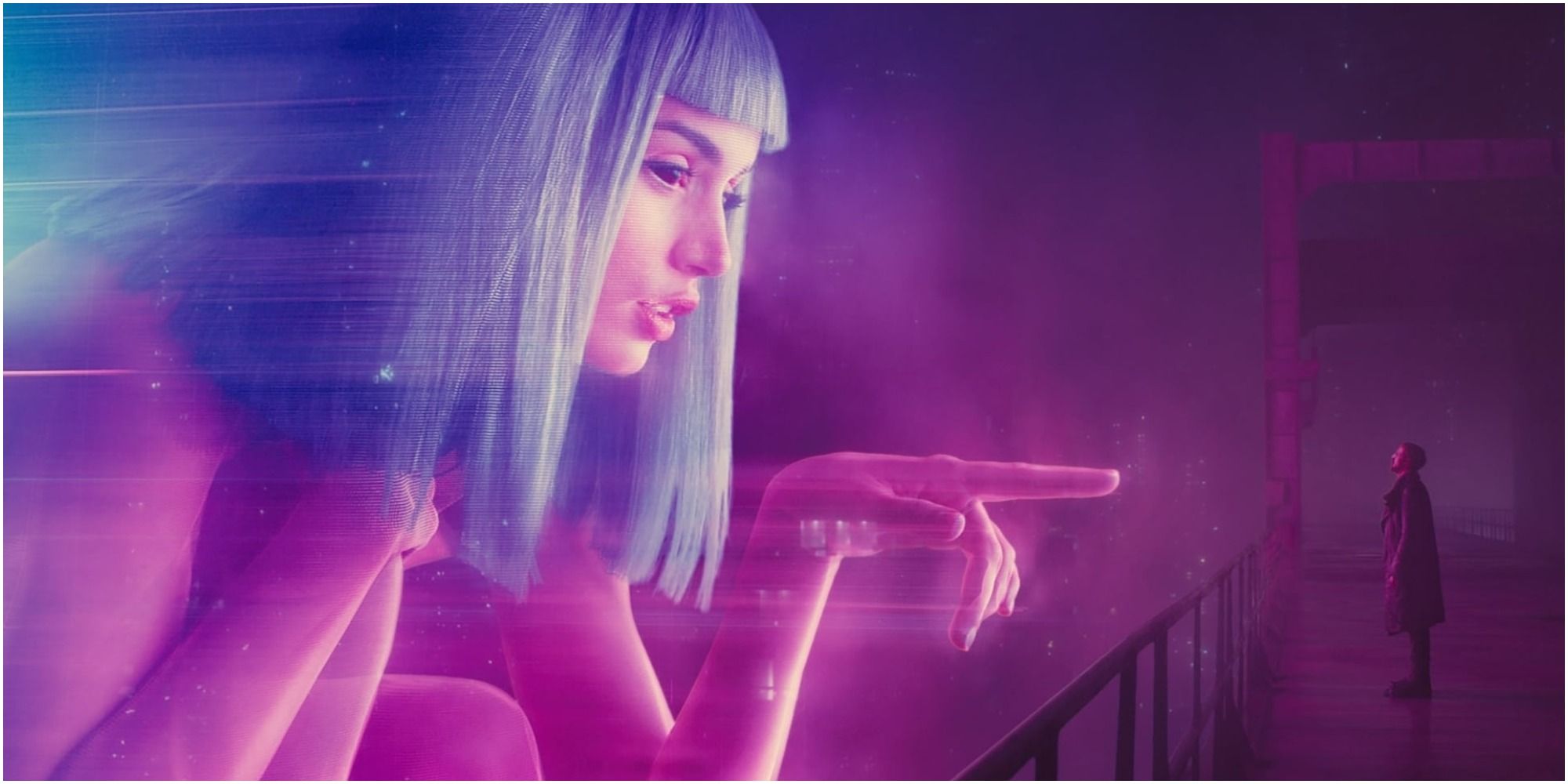

By comparison, Blade Runner 2049 was widely celebrated by critics when it opened in 2017... and yet, a closer look at its reviews reveals a similar divide between the critics who admire its visuals, music, and expansion upon Blade Runner's themes (combined with some surprisingly subversive narrative choices) and those who mostly share their feelings, but find it too slow and overlong for its own good. The sequel was also criticized for under-developing its women characters and how all the women in the Blade Runner universe (replicant and human alike) seemingly exist to kill/be killed and move the plot along. And while Villeneuve later blamed Blade Runner 2049's lack of Oscar nominations outside of the technical categories on its weak box office performance, one has to wonder if perhaps its subtly-divisive reception was equally responsible.

Neither Blade Runner Nor Blade Runner 2049 Are Crowd-Pleasers

With the benefit of hindsight, it's all the more obvious Alcon and Warner Bros. spent way too much making Blade Runner 2049. It was simply never going to be the type of crowd-pleaser that, broadly speaking, could easily recoup a budget of $150-185 million (the estimated price tag for Blade Runner 2049, not counting marketing). Like its predecessor, Blade Runner 2049 is too deliberately slow and atmospheric to have the same crossover appeal as similarly smart modern sci-fi movies like Inception, Gravity, and The Martian. Even then, it still cost much more to produce than most of those hits did, which only furthered hindered its ability to break even financially. Villeneuve's critically-acclaimed extraterrestrial drama Arrival (which he made right before Blade Runner 2049) wasn't an exception to the rule, either; it too would've been a commercial dud if the director hadn't kept the price tag down to a modest $47 million.

The Original Blade Runner Had a LOT Of Competition

Blade Runner wasn't exactly an inexpensive movie either and was budgeted at $30 million unadjusted for inflation (for context, that's $3 million less than The Empire Strikes Back cost to make two years earlier). It actually performed pretty well in its opening weekend, though it struggled to have legs in the weeks that followed. In fairness, it was partly a matter of timing; Blade Runner arrived three weeks after Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and two weeks after E.T., so competition for sci-fi films was really intense right out the gate. If that wasn't enough, it also premiered the same day as John Carpenter's The Thing remake, another R-rated movie similarly targeted at older audiences. Given the alternatives (including, other genre crowd-pleasers like Conan the Barbarian), it's no wonder fewer ticket buyers turned out for Scott's comparatively moody and dreary sci-fi vision. It wasn't the only one that got lost in the shuffle, either; The Thing was likewise a box office failure that went on to achieve cult status years later.

Blade Runner 2049 Didn't Learn From The Original Movie's Mistakes (& Made More)

When push comes to shove, Blade Runner 2049 didn't learn from its predecessors's missteps. It was too slow and long (something that came up in a lot of reviews, even otherwise glowing ones), and Scott himself has said he would've dropped thirty minutes of it. The film's sexism didn't come out of left-field either; the original Blade Runner isn't any better about examining the violence (both physical and sexual) it subjects its women characters to. On top of all that, the marketing for Blade Runner 2049 was extremely secretive and revealed little in the way of details to help get audiences excited for a return to this particular sci-fi universe. A franchise like Star Wars can get away with super-secret marketing because its plots are ultimately quite straightforward and the visuals are exciting enough to sell themselves; it's another thing when you're trying to convince anyone who isn't already a Blade Runner fanatic that a movie full of scenes of Gosling non-emoting against dystopic backdrops is something they'll watch to check out.

Still, there are probably a number of Blade Runner fans who don't mind that both movies bombed. Each film tells a satisfyingly standalone story and doesn't leave major plot threads dangling as a set-up for a future sequel or spinoff (as so many franchise movies do). Blade Runner 2049 especially feels like it truly represents Villeneuve's uncompromising vision and not something that was reworked to be more bankable, the same way the best cuts of Blade Runner have Scott's fingerprints all over them. As movie buffs and sci-fi fans know all too well, it's sometimes (usually?) better to have too little of a property you love than too much of it.