Warning: Spoilers ahead for Berserk, which is a MATURE comic

Though the original creator may be gone, Young Animal Magazine’s Berserk will still go down as the finest manga of all time. With the world still reeling from the tragic passing of revered mangaka Kentaro Miura, many fans are still lamenting that his great work, the seminal, long-running, dark fantasy epic Berserk, will never see completion by his hand. A consummate tale richly woven with strands of drama, action and often nightmarish imagery, Miura enthralled, and often disturbed, fans for more than thirty years with his fascinating and often profane saga of Guts, the Black Swordsman, as he wanders a medieval fantasy world in search of redemption, battling a ceaseless army of demons and monsters along the way. It is clear that, regardless of its conclusion, Miura has built the legacy of Berserk on strong foundation with a master’s exhibition of skillful and fearless storytelling, and Berserk will endure as the best of the best.

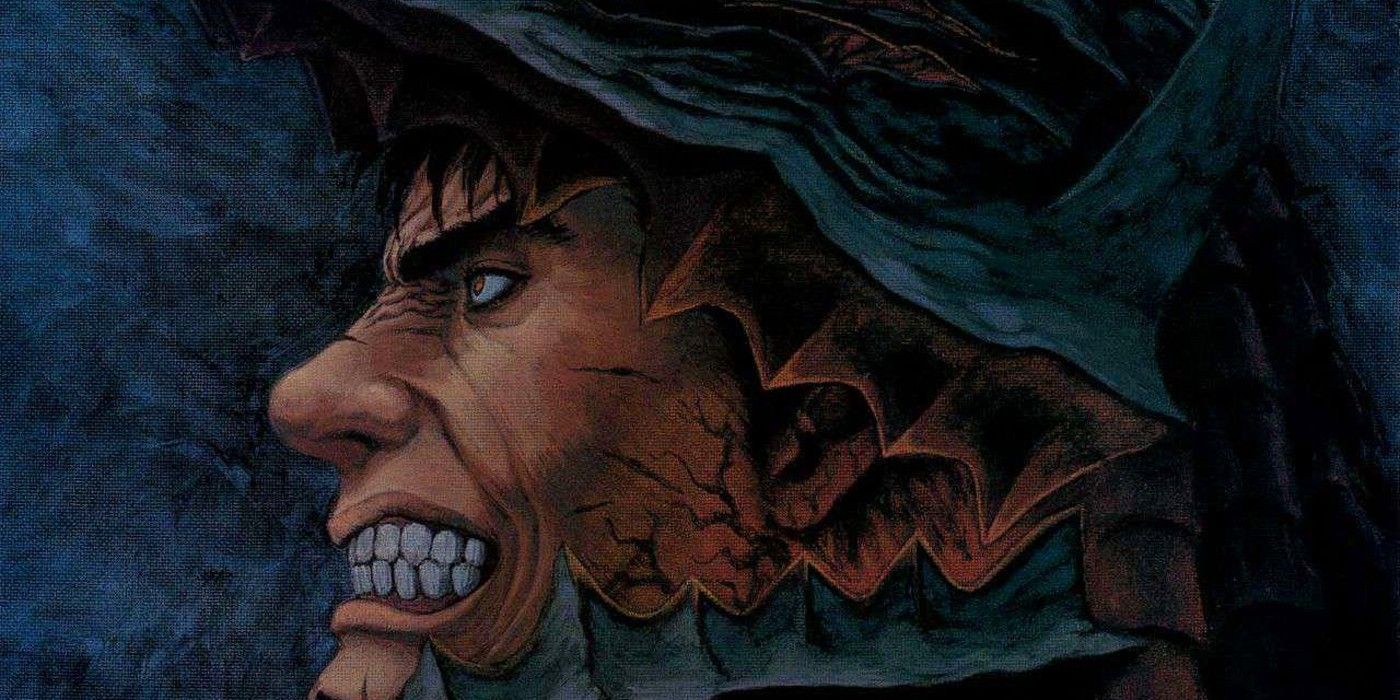

When Berserk first began in 1989 in the pages of Monthly Animal House, no one could have guessed the influence Miura would have on popular culture, with industry luminaries as varied as Hidetaka Miyazaki (Dark Souls) and Samuel Deats (Castlevania) paying homage to Miura’s imagery in their own works, with some fans even noticing similarities to key scenes in the Russo Brothers’ Avengers: Infinity War. Though perhaps a tinge overly grimdark in his early appearances, Miura would over time develop Guts into a sophisticated archetypical dark hero, a lone warrior who must learn to trust his allies again after a lifetime of unqualified suffering. Looking at Berserk’s three decade-long run, the greatest triumph Miura can claim is his personal evolution as a writer and an artist, and it is in his dedication to produce such a milestone title that readers can find the character of the man in his work.

A Journey Through An Everlasting Night

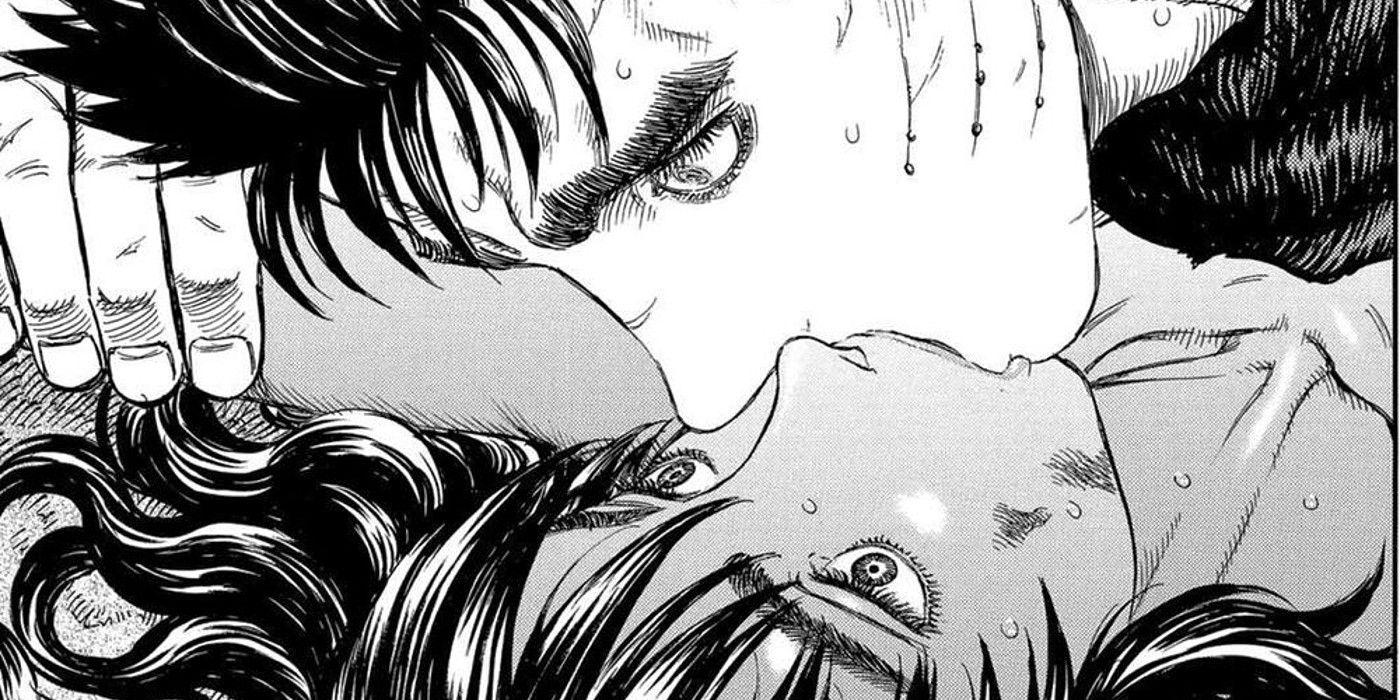

What might be Miura’s greatest contribution to the culture-at-large would be his work in constructing the unique dark fantasy atmosphere of his epic, most notably through his great antihero, Guts. Beginning as little more than a ravening beast possessed of almost childish stubbornness, Guts would eventually grow into a surprisingly multi-layered character whose resilient humanity provided a brilliant touchstone to the sometimes elusive emotional core of the series. A young mercenary in the service of the future-villain Griffith and his Band of the Falcon, Guts' hard luck life took an even harder turn when he comes face-to-face with the demonic forces that secretly governed his world. This event known as “The Eclipse” concluded with Guts losing his comrades-in-arms (along with one of his arms) and witnessing his lover Casca be sexually assaulted by Griffith as part of a hellish sacrifice to attain godlike power.

Even in a morally stark situation such as this, Miura was never one to accept easy answers, and wrote Guts as an eternally atoning revenger, who would often find himself committing brutal acts throughout his journeys in part due to the trauma of having survived such an event. As a seinen hero (or 18+ in Japan), Guts was a hero for an older audience, and so Miura made sure the horrific tragedies of his stories had consequences for his characters. Often, the series would depict Guts struggling to keep his inner violent, self-destructive impulses at bay, culminating in bouts of possession where Guts would literally attack the now-helpless Casca. Given that Guts’ main quest throughout the series would become ostensibly to protect Casca after she had been mentally reduced to the level of an infant following her attack, it is clear what Miura intended to communicate: even heroes can and do commit heinous acts when overpowered by the influence of an evil world.

This complex yet holistic approach was often the basis of many of the finer qualities in Miura’s work. The world of Berserk was one where ghosts and demons exerted tremendous control not only as physically monstrous or politically powerful creatures, but also in being able to cast their malice through an invisible psychic plane, a plane Guts was now eternally bound to after being marked during the sacrifice. Having to simply exist within this kind of environment was a constant threat for Guts, but the payoff came when the character finally matured, in part from learning he could not handle this heavy burden alone.

In this way did Miura demonstrate his incredible storytelling discipline, allowing the characters, setting and conflict to meld together seamlessly until it was impossible to separate the causality of one element from another. The purity of this ethos is what allowed him to tell even his most controversial stories.

A Man Apart

Much has been said of Miura’s incredibly detailed and versatile artistic abilities, and his development into the superlatively skilled artist he would become over the years is a journey in itself when reading through the series. However, perhaps his greatest attribute in this regard, aside from his nightmare-inducing monster design, would be his fearlessness in the depiction of quite disturbing sexual imagery, often provocative to such a degree as to force the reader to consider the ethicality of the artist himself. Never one to back down, the litany of vivid, horrific phantasmagoria Miura produced could give any other work a run for its money in terms of sheer vulgarity. But there was a method to his madness.

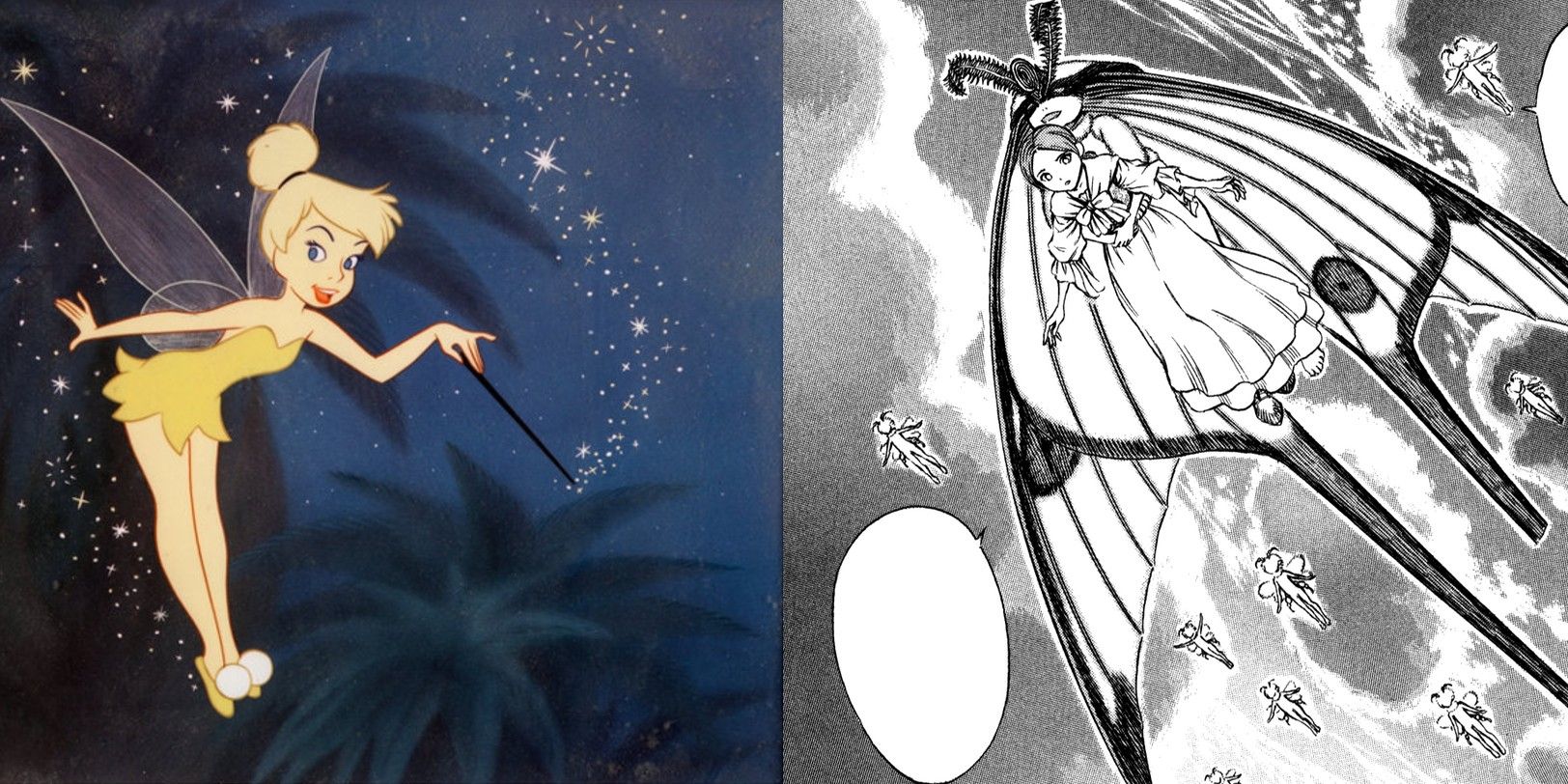

In highlighting many unpleasant tropes sardonically within his own manga, particularly in underage sexuality, sexual violence and violence against children, Miura made clear that he found much of what appealed to the mass-market audience as being subversively harmful and, beyond that, creatively abusive towards the audience. One of his particularly difficult story-arcs featuring the villainous apostle Rosine can be interpreted as a dark lampoon of Disney’s Peter Pan, particularly in the design of Tinkerbell, and clearly condemns Disney’s normalization of casual sexuality aimed at children. In this way, even his most controversial decisions, including Griffith’s assault on Casca, can be understood as Miura railing against the industry from which he arose: the entertainment industry itself, and the perceived attraction of sex and violence which ran rampant regardless of the audience.

Kentaro Miura may be gone, but Berserk will remain a testament to the man himself, and his harrowing story a frightful reminder of not only the darkest recesses of the human heart, but also to what a great storyteller can accomplish when given free rein.