This author is of the mind that an opinion piece should make the opinion in question crystal clear, so here it is: The idea of an R-rated "adults only" movie about Superman is a perversion.

That usage of "perverse" is, of course, not intended to be taken in the actionable sense; the idea in question isn't an "obscenity." The purported "R-rated Director's Cut" of Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice should not be banned, censored or restricted by any means outside those already established by the rating itself. The decision to produce it as such is not only allowable, but also artistically and creatively valid: If DC Entertainment, Warner Bros., director Zack Snyder and everyone else involved have decided to produce a movie featuring three iconic pop-culture figures originally created for an audience of school-age children, and beloved by generations of the same, that is so sadistically violent and/or gratuitously explicit that it can easily be made to qualify for a rating that declares it (proudly, no less) unfit for those very children, they have every right to do so.

But it's an awful idea, one that along with sounding like something out of an Idiocracy-style satire of a dystopian cultural-wasteland ("Now Playing: Batman, Superman & Wonder Woman: Not Suitable For Children Under 17!") implies depressing things about the nature of the film itself and the fate of the DC Cinematic Universe intended to be launched by it - and could very plausibly mean catastrophic things for the superhero genre as a whole.

Does that make you angry? If so, it's not exactly surprising. Just about the most controversial thing you can say in the 21st century version of geek culture is that comic-book superheroes are for kids. You don't want to get caught opining that the target audience for stories about ostensible adults who respond to traumatic life-events by dressing up in primary-colored pajamas and wandering around looking for wrongs to right - usually in form of nicknamed, elaborately-attired criminals - might not be one that has reached the age of maturity.

In some respects this seeming contradiction is understandable: We tend to form our entertainment preferences fairly young, and as such the very foundation of "fandom" as a concept is often about maintaining a long-term appreciation for something that originally appealed to us in our younger days. But the fandom cultures built on those foundations are typically about increasing the depth and breadth of that appreciation by discovering (or inventing) new ways of looking at and enjoying a particular favorite fascination; and the last thing anyone wants to hear about something they're passionate about is "Why bother, that's stupid" - or, in this case, "That's for kids."

Comic book fandom has always seemed especially sensitive to this paradigm, particularly where it concerns superhero books published by the likes of Marvel and DC. With interconnected universes of mythology that reward broadly-interested long-term readership and ongoing decades-long continuities, it's easy for these stories to engender an ongoing personal connection with their most devoted readers. Those readers often felt as though their favorite characters were growing and changing alongside them, and resented the implication that they should outgrow something that wasn't static in the way a cherished childhood toy or a nursery rhyme does: The story ends for your teddy bear the moment you stop imagining that he has one, but Spider-Man always has new stuff going on.

"For kids" is too often used as a shorthand for declaring something to be simple, shallow or not worthy of serious consideration - and both fans and creators of sequential art can attest that the medium has been taking itself seriously and yielding work of depth and worth long before mainstream pop-culture started to pay attention. Indeed, the popular notion that comics didn't start to "grow up" until Stan Lee and Jack Kirby thought to give literalized foibles to The Fantastic Four ignores everything from Will Eisner's genre-transcending work on The Spirit to William Moulton Marston's psycho-sexually fascinating Golden Age Wonder Woman stories.

So it's understandable that, when certain creators started publishing superhero books that took established characters and archetypes to dark, violent places in the mid-1980s, adult fans seized on "Comics: Not Just For Kids Anymore!" as not just affirmation but as a rallying cry for them to come out as adult fans of superhero fiction. And it's also understandable that the industry would respond by catering to this newly out-and-proud audience.

Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns and Miracleman (aka Marvelman - long, long story) all hit within a few years of one another in the early to mid 1980s and drew massive, industry-rocking acclaim (and big sales) by mixing classic traditional superheroes (or superhero archetypes, in the case of Watchmen) with dark themes, extreme violence and explicit sexuality. In response the industry opted to transpose the surface-level trappings of those works - mostly the violence and self-consciously aggressive "edginess" - into their mainstream books. The short-term results were huge sales, but in the long-term it was the beginning of a myopic focus on the older (and, it must be said, predominantly masculine) consumer that created and helped foster the "collector bubble" that ultimately popped in the mid-90s - causing the near-implosion of the entire comics industry.

And now it looks like superhero movies are in a mad dash to repeat the same series of mistakes all over again.

The ink was hardly dry on the newspaper headlines proclaiming that the R-rated Deadpool had become a bigger box-office champ than many of its more "accessible" PG-13 cousins than did the all-too-familiar drumbeat begin: "The next Wolverine should be R-rated, too!" and "How about X-Force: an entire team of R-rated superheroes!" With Deadpool still enjoying its successful stay at the box office, it was announced that Batman V Superman, already being criticized for seemingly continuing Man of Steel's controversially brutal vision of DC Comics heroes, will receive an R-rated "director's cut" on DVD.

From a business standpoint, it makes sense. Batman V Superman remains dogged by reports (like this infamous filing from HitFix) that Warner Bros. is still not convinced they've cracked the formula for a superhero movie that will please audiences enough to get them invested in the hefty upcoming slate of DCEU titles. The promise of a home-video double-dip (i.e. if you didn't like it, maybe you'll pick up the "Director's Cut" to see if it changes your mind), makes a certain amount of cynical sense - as does chasing after the trend for R-rated superheroics supposedly conjured by audiences' embrace of Deadpool.

But while it makes a certain amount of balance-sheet sense, it also implies a fundamental misunderstanding of what seems to have made Deadpool resonate with moviegoers well beyond the promise of X-Men characters actually slicing-up and shooting people - and it's not hard to extrapolate that it's the same misunderstanding of Watchmen etc. that doomed things for comics in the 90s.

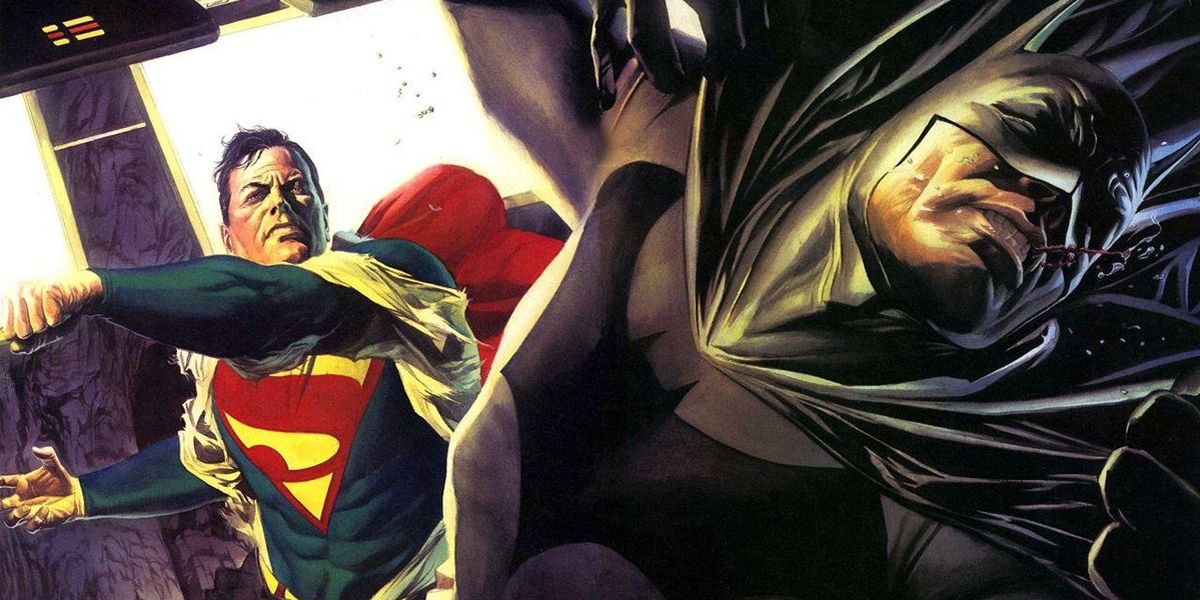

What the comics industry (and, to be fair, a sad plurality of comics fans) failed to grasp about the ultra-violent superhero works put out by the likes of Frank Miller and Alan Moore in the 80s was that the "R-rated" content wasn't just there to show off: It was making a point - a satirical point. The fact that Batman, Superman, etc were originally designed for children and are by-and-large inseparable from that aspect of their inception wasn't something that those books were trying to "transcend," it was a fundamental building-block of their satire: What Moore and Miller understood was that children's characters acting out "adult" sex and violence is - here's that word again - perverse (literally: It's a perversion of the material and its intent); and by perverting those characters and/or their genre tropes, the authors turned them into caricatures to deliver a point.

In Watchmen, the point was self-criticism: In that book's alternate history, the publication of Superman led to real-world imitators instead of comic-book knockoffs, and by migrating from fiction (where they can inspire us) to reality (where they can only let us down) these "real life superheroes" wind up destroying their lives, their bodies, their loved ones and eventually the world. The Dark Knight Returns used a dystopian vision of a near-future DC Universe and caricatures of an older Bruce Wayne and Clark Kent to mock the then-current social politics of the Reagan Era. Marvelman/Miracleman, like Watchmen, effectively argued against its own existence, explicitly showing how applying the inescapably childlike worldview of the superhero genre ("good" and "evil" as tangible, clearly-defined things) to a real world can only ever end in fire and blood.

But too many fans of the day, so viscerally charged at the mere sight of blood-splattered Batarangs and media outlets finally treating "their" medium with respect, managed to miss the point: Watchmen was about a fall from grace, but they read it as an "elevation" of the form. Dark Knight Returns' blighted future DCU was a warning, but was seen as an ideal for the "real" DCU to strive toward. And so we got Superman being beaten to death by a boring brute, Batgirl sexually-assaulted, paralyzed and confined to a wheelchair, and dozens of "gritty" and "Xtreme!!!" reboots all throughout the 90s. And then a bubble, and a burst, and an industry that collapsed in on itself and might have vanished completely if not for - irony of ironies - lucrative TV and movie deals that had gotten younger generations largely left ignored by adult-collector obsessed publishers hooked on more traditional versions of their characters. Seriously - it's hard to find any big fans of, say, Batman, Spider-Man or The X-Men under 25 who didn't discover them first as cartoon or movie characters rather than in the comics.

However, none of this is automatically an argument against an R-rated Batman V Superman - or, more broadly, a Batman V Superman that can easily be made to be R-rated. The "subtext" here is that Zack Snyder already made an adults-only version of this movie, and the "Director's Cut" represents what they had to take out to get a PG-13 for theaters. That it's (in this author's view) a poorly-conceived idea that could take comic book movies down a path to ruin already walked by comics themselves doesn't mean that Snyder and company shouldn't make exactly the movie that lines up with their personal artistic vision of the characters and story - they should, because that's what filmmakers and artists of all stripes should do.

But that doesn't mean it's going to work.

The fact is, most comic book superheroes are fundamentally children's characters. That's not a criticism, a value-judgement or an "insult," it's a statement of fact. Excluding characters designed expressly for the adult audience on the independent/underground scene (or outfits like Image in the 90s) the vast majority of these characters were created very specifically with an audience of children in mind. They were meant to sell magazines full of ads for cheap toys and novelties to young children with small amounts of disposable income. That doesn't mean they weren't well-written or that their authors didn't care about them, it simply means they were meant to be enjoyed by kids first and foremost - just like Harry Potter, Steven Universe, C.S. Lewis' Narnia books and any of a thousand properties also enjoyed by grownups. And while its certainly possible to bend and repaint a property into a different shape... you can only apply so much paint before you've obscured everything relevant about the original; you can only bend a thing so far before it breaks.

And the problem with bending characters like Batman and Superman so that they become "adult" is that neither of them bend all that far in that direction - especially without shedding an increasing amount of what fans liked about them in the first place. Christopher Nolan's Dark Knight trilogy gave the world the closest thing to a "realistic" Batman as possible, but only after throwing out or drastically minimizing everything from Robin to the Batcave, to Lazarus Pits, to Bane's actual powers, to Joker's proper skin, to Catwoman actually dressing like a cat. The list of "silly" or "childish" things you have to strip away from Superman in order to make him feel like he belongs in Man of Steel's semi-realistic action movie world - the glasses disguise, the Fortress of Solitude, portions of his costume, the "because it would be boring" disregard for a clear limit to his abilities, or lack thereof - eventually leave you with a character sorely lacking in distinctive traits beyond the ability to cause generic disaster-movie destruction.

Why does Bruce Wayne, who lives alone in a huge mansion, need a special cave for all his Batman stuff instead of keeping it in his dozens of spare rooms? That's a boring grownup question that the audience Batman was created for already knows the answer to: Because a special clubhouse where you keep all your coolest stuff that only you and your friends know about is awesome. Why does Superman need a secret identity, exactly? Because secrets are fun to have (and are, pointedly, one of the few ways children can hold and exercise power over adults in their daily lives). Why don't they just use guns? Because lassos, magic hammers, boomerangs and ricochet-shields are cooler than guns, and that makes plenty of sense for kids. So does the idea of The Hulk getting stronger as he gets angrier - a potent power fantasy for audiences whose best/only method of getting their way is to clenched their fists and stomp their feet. What does talking to ants have to do with shrinking powers? Without the ants, Ant-Man is just "Smaller Man," duh. Any ten year-old can explain that one.

But even if it turns out to be wholly possible for the first cinematic meeting between the Holy Trinity of DC Superheroes and the gateway-film to an entire DC Cinematic Universe to not just work but work exceptionally well - if Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice is actually a good or even great film in all of it's dour grownups-only glory - is that really what we want? Should it be?

The hard work of good creative professionals is what allows fans to stay devoted to a character like Superman, whom they discovered as children, well into adulthood. That they continue to be discovered and embraced by each successive generation speaks to something more potent, more elemental and more powerful about these figures on an intrinsic level. For all the highly worthwhile academic reconsideration of comic book superheroes as the modern inheritors to the place gods and monsters once held in our collective mythology, at the end of the day it still comes secondary to what they mean to those who came to them without first reading the collected works of Joseph Campbell. To call them simply "power fantasies" (however accurately) diminishes their great import as wish-fulfillment ideals for those still young enough to have more wishes than regrets.

The idea of Superman - the man who can fly, who can't be hurt, who isn't bound by the laws of physics and who uses that immeasurable power only to good - means something and has continued to mean something to generations of children for whom his lack of limitation is the wish-dream antithesis of their relatively powerless place in the social order. Do we really want to, from a certain perspective, take that away from them? Make "the" Cinematic Superman a figure whose movies simply aren't for them anymore because we want to see him twist peoples heads off and/or get beaten bloody by a powered-up Batman? Speaking of which, do we want to continue denying those same children the "classical" Batman who stands as an ideal of overcoming unimaginable (especially to a child) loss through self-determination because we're more interested in a brooding billionaire bully driven by vengeful paranoia? Is it okay that Wonder Woman, the iconic female superhero beloved by legions of young girls, will take her first big-screen bow as a secondary-player in a movie so aggressively disinterested in audiences outside the 35 year-old fanboy demographic?

Maybe Batman V Superman will be a good movie. Maybe it will be a huge hit. Maybe both or neither of those things will happen. But the last time "regular" superheroes went chasing after the earnings of an adults-only satire they didn't fully grasp was a satire, the whole genre suffered. And even if it doesn't this time, are the depths of darkness, brutality and despair really where The DC Cinematic Universe - and all of the boundless, imaginative, colorful, adventurous tales that are the birthright of such a concept - should be launched from?

One way or another, we're about to find out.

Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice opens on March 25, 2016, which is followed by Suicide Squad on August 5, 2016; Wonder Woman on June 23, 2017; Justice League Part One on November 17, 2017; The Flash on March 16, 2018; Aquaman on July 27, 2018; Shazam on April 5, 2019; Justice League Part Two on June 14, 2019; Cyborg on April 3, 2020; and Green Lantern Corps. on June 19, 2020.