In Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s classic graphic novel From Hell, the Jack the Ripper murders are shown to be part of a magical ritual that reinforces the power of the patriarchy over the course of the 20th century. While Moore plays with a combination of real and invented history, the story’s deeper meaning is a metaphorical one.

In the real world, the Jack the Ripper murders were a tragic spree of serial killings that claimed the lives of at least five women in 1888 in London’s East End. The killings became a media sensation and has been ingrained in the public consciousness ever since, due to the gruesome nature of the murders, the speculation over the killer’s identity and the fact that the case was never solved. In From Hell, the Jack the Ripper murders are fictionalized to be part of a vast royal coverup. However, their perpetrator, Sir William Gull, has an ulterior motive for committing these crimes. Gull, a freemason, believes London to be a profoundly mystical city from which he can cast a vast ritual using the killings.

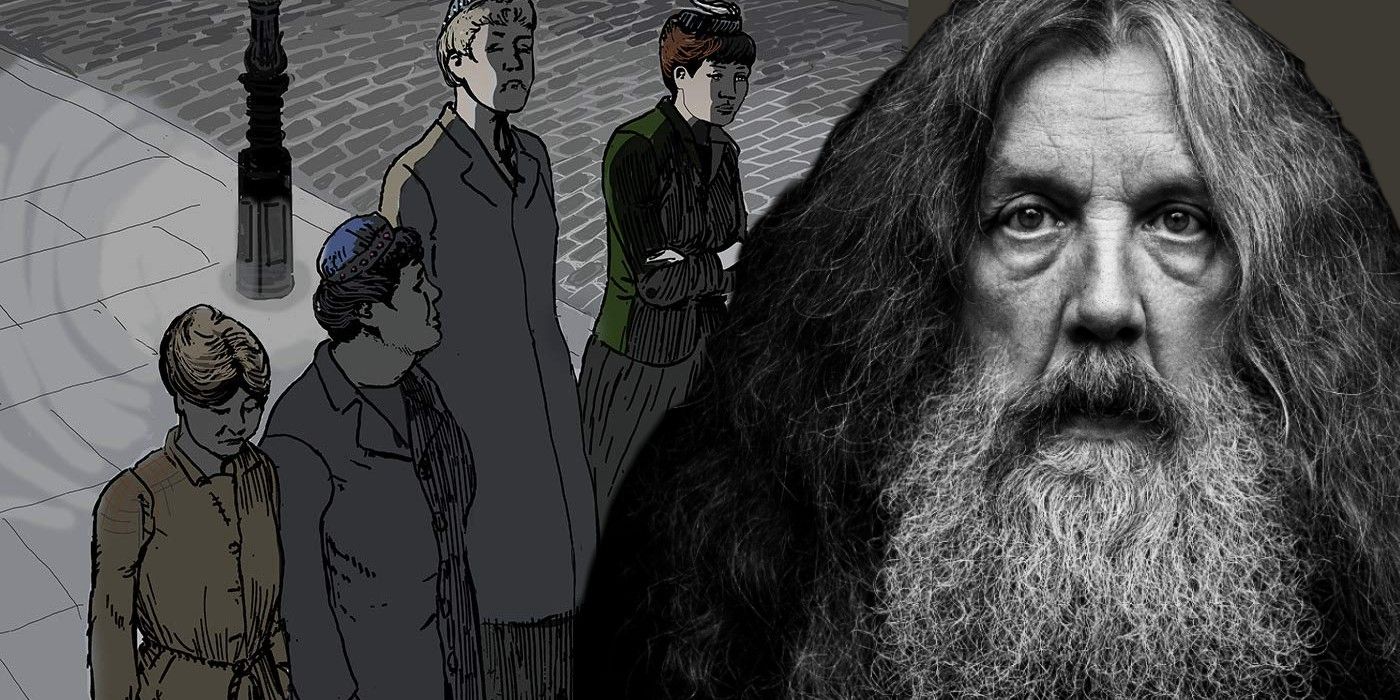

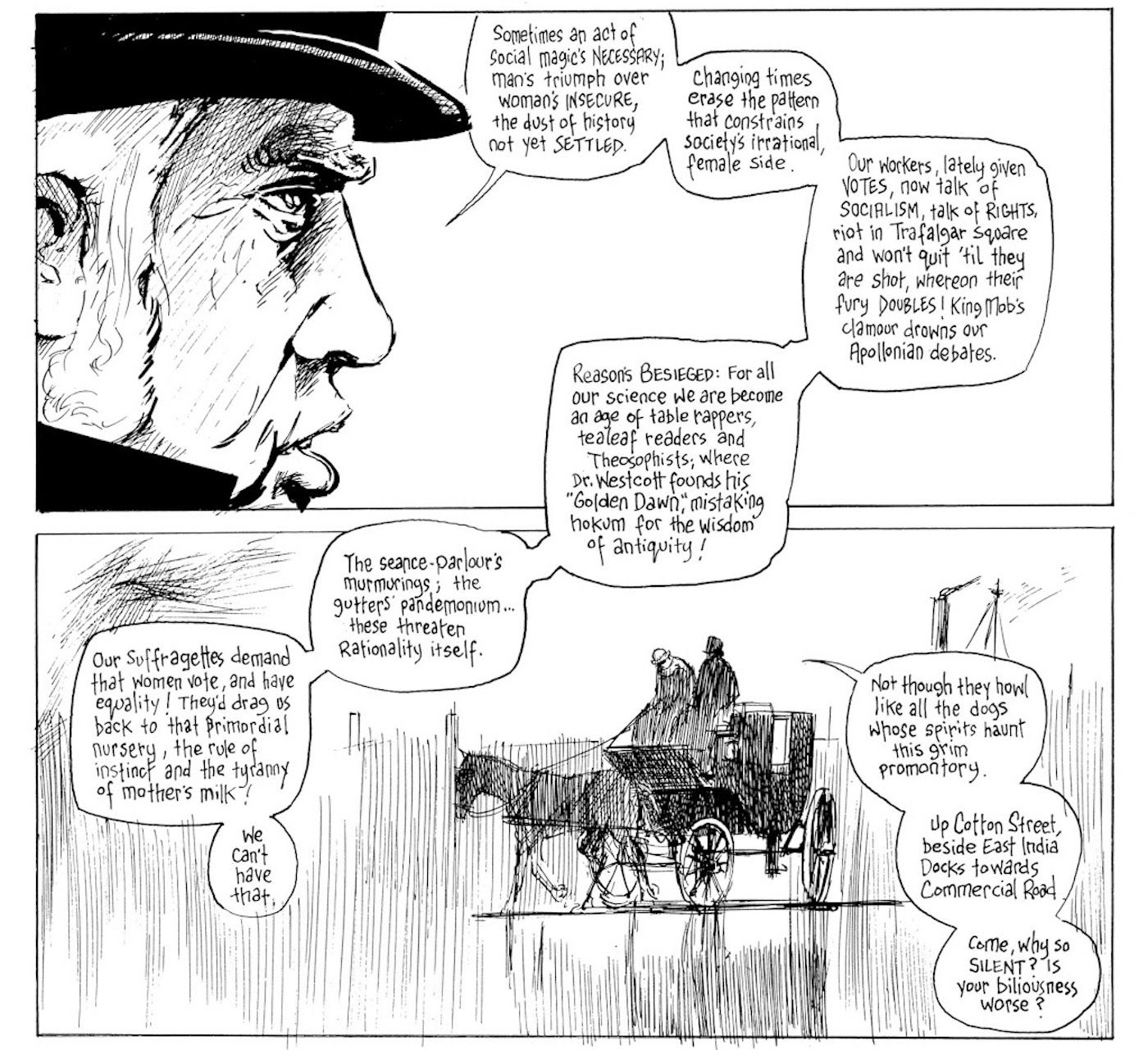

The purpose of Gull’s ritual is to stop the liberation and equality of women, which Gull believes will accompany the dawn of the 20th century. In Chapter 4 of From Hell, Gull expresses his Masonic beliefs on the superiority of men over women by explaining what he believes to be the secret history of various London locations to his coachman John Netley. In Gull’s mind, the connections he can draw between these places and the historical and mythological subjugation of women mean that they can act as pieces in the ritual he’s performing. As Gull commits more murders and his mental state deteriorates, he experiences visions of the coming century, which imply that his ritual does succeed.

While women lacked many rights in 1888, a tide was slowly turning. By then, early British suffrage movements were gathering steam and would coalesce into larger organizations around the turn of the century, eventually leading to full suffrage. However, despite this victory women still continued to fight for equal rights throughout the 20th century and beyond. By implying that Gull’s ritual succeeded, Moore is presenting a pessimistic view of how for all its advances, the 20th century, with its wars and horrors, failed its potential. It’s a bleak outlook, but one with a small silver lining. As Gull dies, his spirit travels into the future, where he finally sees Mary Kelly, the only intended victim of his who escaped. Kelly then senses Gull in some form, banishing his spirit “back to Hell.” Kelly’s survival is only a small victory, but it’s a victory nevertheless.

Gull’s hatred and implicit fear over the advent of women’s rights wasn’t something limited to him either, in the real world and in the comic. Metaphorically, From Hell isn’t simply Gull attempting to fight against change, it’s patriarchal society attempting to fight it. Throughout From Hell, Moore shows the culpability of the entire system from the top down; From the British Royal Family who condemn Annie Crook, an innocent woman, to an asylum to cover their infidelities, to the shopkeepers and passers-by who show no sympathy towards the victimized sex workers Gull kills. Gull may be uniquely horrible, but he’s not the cause of this societal rot, only a symptom in microcosm. As much as Gull believes London represents his ideas, he also represents its. And whether Gull is right or not about the mystical misogynistic power embedded in London isn’t even important. That’s the point Alan Moore is trying to get across, whether in From Hell or in real history, the society which Gull exists in is already broken, with or without magic.