ar

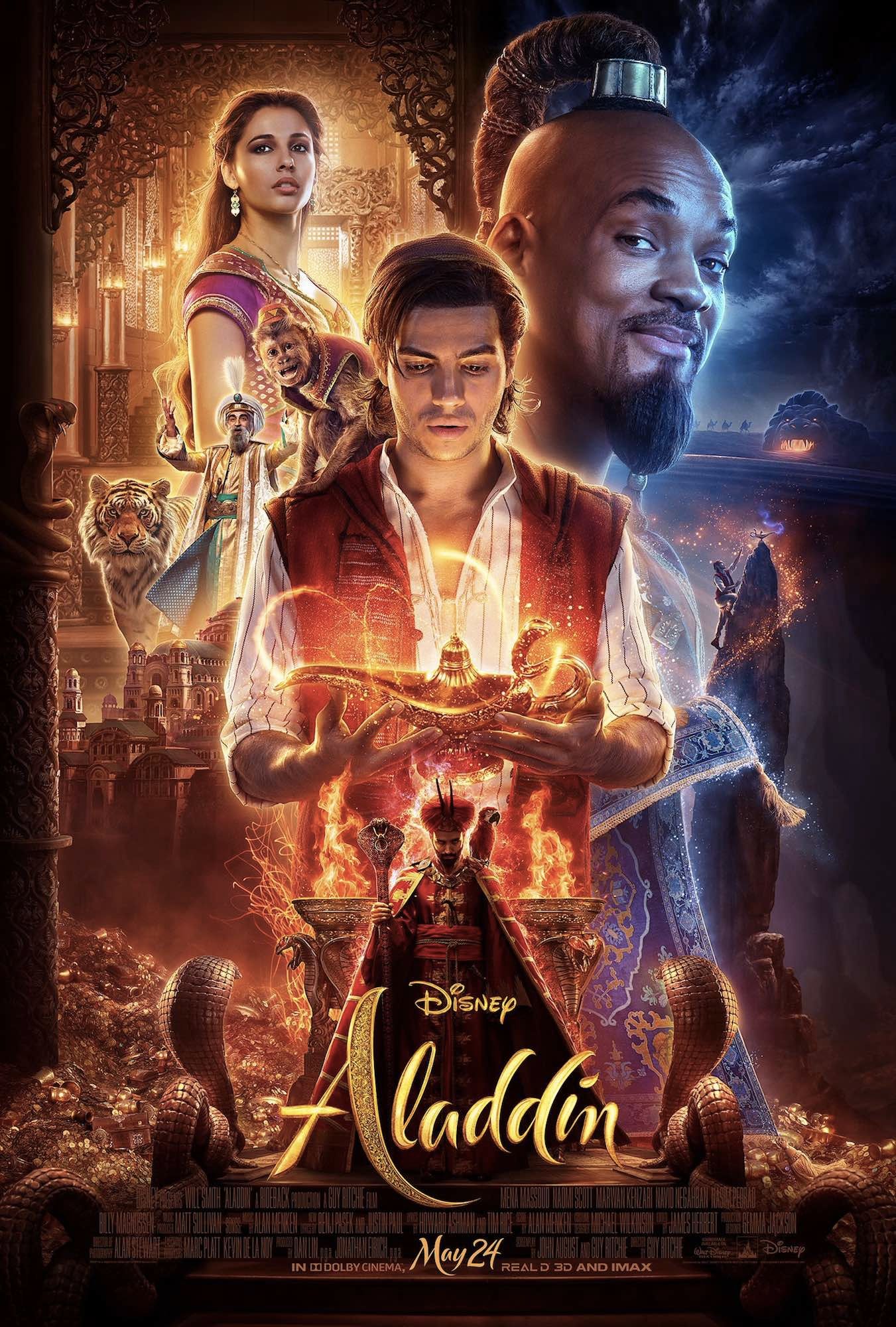

One of the biggest announcements coming out of D23 was the news that Guy Ritchie had cast his leads in the live-action Aladdin movie. Speculation of Will Smith’s casting as the Genie was confirmed, and after months of auditions, which took place across the world, the leads of Aladdin and Princess Jasmine were filled by little-known Egyptian-Canadian actor Mena Massoud and Power Rangers star Naomi Scott.

Unsurprisingly, there was a social media backlash over the casting, mostly to do with the casting of Jasmine (Scott is half-white, half-Indian). This was because Disney had put out a worldwide casting call for young men and women of Middle Eastern or Indian descent to audition for the roles of Aladdin and Jasmine, with over 2,000 people applying, and while Scott does have Gujarati heritage she is, aesthetically speaking, probably the whitest non-white actor they could have possibly cast.

The casting choice has been cited as the latest example of the film industry's colorism - a form of prejudice which sees actors and, especially, actresses of color with a darker skin tone overlooked and less featured on screen than those with a lighter skin tone. It's understandable, then, that many fans of color were disappointed with the Jasmine casting, as they saw the live-action Aladdin film as not only an opportunity for non-white representation on screen, but also to represent an ethnic aesthetic authentic to the Arab world that the fictional Agrabah is set and inspired by. Scott’s casting doesn’t exactly support this notion because unlike Princess Jasmine, she is mixed-race, light-skinned and of Indian and not of Arab descent. However, this latter point is not entirely clean cut as the original Aladdin story isn’t entirely a Middle Eastern tale, begging the question: should Aladdin and Princess Jasmine be Arab, Indian or Chinese?

Aladdin first appeared in One Thousand and One Nights, a famous collection of Middle Eastern folk tales from the Islamic Golden Age (between the 8th and 13th Century) which was first translated into English, and renamed the Arabian Nights, over 400 years later. The stories are not just Arabic tales, but also have roots in Persian, Mesopotamian, Indian, Jewish and Egyptian folklore and literature. The story of “Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp” didn’t even appear in the collection until French translator Antoine Galland added it in 1710. According to Galland’s diaries, he had heard the story from a Syrian scholar in Aleppo - but no one has actually been able to find an original Arabic source for it.

Galland’s tale isn’t even set in the Middle East - it’s actually set in a Chinese city, and Aladdin is not an orphan but a poor Chinese boy living with his mother, with the only other location mentioned in the story being Maghreb, North Africa, where the sorcerer is from. The assumption of a Middle Eastern origin comes mainly from the character names, like Princess Badroulbadour, which means “full moon of full moons” in Arabic. The Sultan is referred to as such and not in Chinese terms as “the Emperor,” and other characters are clearly also Muslim, not Buddhist or Confucians, as their dialogue is filled with devout Muslim remarks and platitudes.

While Chinese Muslims did exist - the Hui being the most famous, dating back to the beginnings of the Silk Road - Galland’s version of the story is indicative of the Orientalist tradition of Western storytellers that sees the conflation of diverse Eastern cultures into one. As Krystyn R. Moon explains in Yellowface: Creating the Chinese in American Popular Music and Performance, 1850s-1920s:

“Aladdin, which most people today associate with Persia and the Middle East thanks to films such as The Thief of Bagdad (1924) and Disney’s Aladdin (1992), was one of the more popular nineteenth-century productions set in China because of its romantic and moralistic storyline and its potential as a spectacle...Composers and librettists sometimes chose Persia as the setting for the tale because One Thousand and One Nights was from that region of the world and, like China, was a popular imaginative space for Americans and Europeans.”

This “imaginative space” allowed white Westerners to purport an unrealistic and fantastical impression of Eastern cultures, which for many people of Arab, Indian and Chinese descent is not exactly representative. Disney’s 1992 animated film imagined up a fictional Middle Eastern city to set its story and replaced nearly all the original character names with ones stolen from The Thief of Bagdad, another movie based on “Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp” and written by white filmmakers too.

Page 2: [valnet-url-page page=2 paginated=0 text='The%20Disney%20Movie']

Directors Ron Clements and John Musker drafted the first script of the Disney animation - inspired by Linda Woolverton’s screenplay, which was in turn based on lyricists Alan Menken and Howard Ashman’s original story pitch - with Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio brought in to rework the story entirely, removing key characters and plot points. Thus, the 1992 Aladdin film became even more of an Orientalist fiction than the original story, and presented an Arab world as imagined by seven white American writers.

This live-action Aladdin remake will once again be helmed by a predominantly white team of filmmakers, with John August penning the original script and Game of Thrones’ Vanessa Taylor brought in for rewrites, while Menken is set to create new songs with La La Land songwriting duo Pasek & Paul. Hopefully in 2017 the songwriters will take a little more care with the songs' lyrics; in the opening number of the original film's “Arabian Nights,” the lyric "Where they cut off your ear if they don't like your face," was changed to "Where it's flat and immense and the heat is intense," after backlash from the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee.

It’s because of this Orientalist approach to Aladdin that some people have argued that the Arab community shouldn’t really want Arab actors and actresses to be cast in the live-action remake anyway. Khaled A Beydoun, an Associate Professor of Law at the University of Detroit Mercy, writes for Al Jazeera:

“To some measure, the demand to cast Arab actors to play the lead roles in Aladdin amounts to an endorsement that Agrabah is indeed an Arab land or an accurate representation of the Arab world. And accepting that sanctions a host of vile stereotypes that attach to and emanate from an imagined ‘barbaric’ region where ‘they will cut off your ear if they don't like your face’. Agrabah is not the Arab or Muslim world, but a spitting cartoon image of the Orient - a centuries' old production of academics and artists, news media and filmmakers, which casts it and its inhabitants as the mirror opposite of everything modern, liberal, and Western.”

Beydoun makes a valid point, but with so few Hollywood films featuring an exclusively Arab, Indian or Chinese cast, it’s no wonder that people of color had high hopes for the live-action Aladdin, a rare film in which they could see themselves represented on-screen in a mainstream movie. If Ritchie's film was based on the original story, the entire cast would be Chinese - apart from the sorcerer, who would be North African - but as it’s said to be a faithful remake of Disney’s animation, Aladdin and Princess Jasmine should really be Middle Eastern or South Asian, despite the film not being an authentic portrayal of either culture.

The casting of Scott, and to some extent Massoud, continues an Orientalist culture of seeing people of color as interchangeable, despite their different ethnic backgrounds. At this point, Disney are hardly going to recast. However, we can hope that the writers behind the remake will attempt to rid Aladdin of some of its more distasteful and outdated stereotypes, and perhaps give Princess Jasmine something to do beyond being whisked away on a magic carpet and being kidnapped by Jafar.