Tomb Raider has set out to do the near impossible: make a good video game movie. This shouldn't be as mammoth a task as it first appears. After all, other kinds of media have been hits on the big screen for generations, with books and comics both receiving stunning film adaptations over the decades. Even board games can see success as a feature film, if 1985's cult classic Clue is anything to go by.In spite of this, the good video game movie is one of the most elusive in the industry, as in reality the number of good video game adaptations, or even passable ones, can still be counted on one hand. Mortal Kombat is a fun action romp, while Silent Hill brings some genuine unnerving moments. The best of the rest, however, instead fall into the guilty pleasure territory: the Resident Evil series, Prince of Persia, the Tomb Raider duology, and Need For Speed. Meanwhile, that Papers, Please short film was a powerful piece, but it still only sits at ten minutes long.Related: The 15 Worst Video Game MoviesIt's not for want of trying, though, as there has been a large number of video game movies released since gaming became a part of the popular landscape. Tomb Raider is not the first to make a real attempt at a good video game movie, and nor will it be the last. It does, however, walk a path in the steps of great, expensive failures. The question, then, remains: why do video game movies do poorly? One potential argument that is sometimes given is that the budget has simply not been there to make these films into something special. However, this is not always the case, and some of the more recent examples have had at least passable budgets on their hands. Assassin's Creed had a budget of $125 million, and Prince of Persia was made for $150 million. Warcraft, meanwhile, had $160 million at its disposal.Even some of the more modest budgets still show a level of underperformance. Resident Evil had a budget of $32 million, which is certainly not the largest amount, but that's still a bigger budget than some of the other top action movies released that year. It's more than both Equilibrium and The Transporter, a pair of films that reached a higher tier than Paul W. S. Anderson's adaptation. It gets even worse when compared to horror movies of that year, with its budget absolutely dwarfing that of Danny Boyle's 28 Days Later, a film that effectively changed zombie movies forever.Some have also raised concerns about the difficulty attracting top talent to these projects, but particularly in recent years this hasn't been a problem. Duncan Jones is a wonderful filmmaker, with Moon and Source Code still held up as strong science fiction movies, yet Warcraft was something of a stumble. Prince of Persia shares a director with Donnie Brasco in Mike Newell, and that film also had the clout of Jake Gyllenhaal behind it. Max Payne was a flop that starred Mark Wahlberg and Mila Kunis. Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard starred in Assassin's Creed. Doom had The Rock, and the original Tomb Raider films had Angelina Jolie.

One potential argument that is sometimes given is that the budget has simply not been there to make these films into something special. However, this is not always the case, and some of the more recent examples have had at least passable budgets on their hands. Assassin's Creed had a budget of $125 million, and Prince of Persia was made for $150 million. Warcraft, meanwhile, had $160 million at its disposal.Even some of the more modest budgets still show a level of underperformance. Resident Evil had a budget of $32 million, which is certainly not the largest amount, but that's still a bigger budget than some of the other top action movies released that year. It's more than both Equilibrium and The Transporter, a pair of films that reached a higher tier than Paul W. S. Anderson's adaptation. It gets even worse when compared to horror movies of that year, with its budget absolutely dwarfing that of Danny Boyle's 28 Days Later, a film that effectively changed zombie movies forever.Some have also raised concerns about the difficulty attracting top talent to these projects, but particularly in recent years this hasn't been a problem. Duncan Jones is a wonderful filmmaker, with Moon and Source Code still held up as strong science fiction movies, yet Warcraft was something of a stumble. Prince of Persia shares a director with Donnie Brasco in Mike Newell, and that film also had the clout of Jake Gyllenhaal behind it. Max Payne was a flop that starred Mark Wahlberg and Mila Kunis. Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard starred in Assassin's Creed. Doom had The Rock, and the original Tomb Raider films had Angelina Jolie. So, where exactly does this failure come from? The lazy argument is, of course, that video games fail to tell good stories. However, this is far from the case. Mass Effect's huge space opera builds a world and plot that most science fiction movies would dream of. BioShock's claustrophobic and paranoid story lives with players to this day. The emotional impact of Telltale's The Walking Dead is seen by many as stronger than that of the original comics or the television adaptation. That said, there's something about the way that these stories are crafted that feels different, and this is where the issues lie.To begin with, the framing of a video game is very different from any other kind of media, and this in turn means that there's little by way of correlation when it comes to adaptation. Games often have a habit of leaving space for player autonomy, which in turn deliberately causes the appearance of gaps in characters and plots for the player to fill. In some of the most important titles in the video game world, the player is either left entirely as an open canvas, or left with no personality whatsoever.Grand Theft Auto 5 is a prime example of this. There is a plot, and a trio of rich characters for the players to control, but their actions are defined by the players. Fallout and The Elder Scrolls leave the character, and effectively the entire story that the player chooses to involve themselves in, up to them. Gordon Freeman of Half-Life is a silent protagonist, a void with no personality. It both leads to a greater level of immersion in Valve's beloved shooters and also leads to anxiety from fans when the notion of a Half-Life movie rears its head again.

So, where exactly does this failure come from? The lazy argument is, of course, that video games fail to tell good stories. However, this is far from the case. Mass Effect's huge space opera builds a world and plot that most science fiction movies would dream of. BioShock's claustrophobic and paranoid story lives with players to this day. The emotional impact of Telltale's The Walking Dead is seen by many as stronger than that of the original comics or the television adaptation. That said, there's something about the way that these stories are crafted that feels different, and this is where the issues lie.To begin with, the framing of a video game is very different from any other kind of media, and this in turn means that there's little by way of correlation when it comes to adaptation. Games often have a habit of leaving space for player autonomy, which in turn deliberately causes the appearance of gaps in characters and plots for the player to fill. In some of the most important titles in the video game world, the player is either left entirely as an open canvas, or left with no personality whatsoever.Grand Theft Auto 5 is a prime example of this. There is a plot, and a trio of rich characters for the players to control, but their actions are defined by the players. Fallout and The Elder Scrolls leave the character, and effectively the entire story that the player chooses to involve themselves in, up to them. Gordon Freeman of Half-Life is a silent protagonist, a void with no personality. It both leads to a greater level of immersion in Valve's beloved shooters and also leads to anxiety from fans when the notion of a Half-Life movie rears its head again. There are ways this can be worked around, of course. Writers can build a character from scratch, and throw them into the world that the video game envisioned, but that then leads to problems of its own. Without that flexibility of character, instead the plot has other matters to contend with, and the drive and desire of this newly fleshed-out lead may not align with what the game initially created. It can cause a tonal shift of the overall plot, with Doom a perfect example of a film that failed to capture the same gut instincts that the game provided.The best video game movies know this, and adjust accordingly. Mortal Kombat is an ensemble cast of cartoonish characters in both the film and the games, and so a slight tweak and a shift towards a little bit of extra camp did the film a world of good. For all its faults, Resident Evil knew when to cut characters and when to change them. Meanwhile, Silent Hill did make some odd changes to be sure, but it took the core concepts of the plot, retained those main themes and desires of the characters, and streamlined it into a solid horror movie.It's not only the character-versus-player dichotomy that causes issues though. Games are also unique in their pacing structure, as the participant has so much more control than in any other media. They have authority over the actions of the characters, in come cases even control over the path of the story itself. In cinema, viewer control comes (at most) from pressing pause, while the reader of a book can only control the text itself by reading at their own pace. In both cases, the core story, and all of its intricacies, isn't going to change.So, there are some subtle difference in terms of what makes a game or a movie fun. Games rely as much on reflexes or active thought as in sound and visual design or acting talent. For some gamers, their favourite moments within the medium come as prolonged shootouts in action games, a particularly fearsome puzzle to overcome, or a long, silent journey in a role-playing game. In short, games are an entirely different beast from the media that have come before them. In a way, it's as difficult to adapt a daydream to the cinema as it is a video game.

There are ways this can be worked around, of course. Writers can build a character from scratch, and throw them into the world that the video game envisioned, but that then leads to problems of its own. Without that flexibility of character, instead the plot has other matters to contend with, and the drive and desire of this newly fleshed-out lead may not align with what the game initially created. It can cause a tonal shift of the overall plot, with Doom a perfect example of a film that failed to capture the same gut instincts that the game provided.The best video game movies know this, and adjust accordingly. Mortal Kombat is an ensemble cast of cartoonish characters in both the film and the games, and so a slight tweak and a shift towards a little bit of extra camp did the film a world of good. For all its faults, Resident Evil knew when to cut characters and when to change them. Meanwhile, Silent Hill did make some odd changes to be sure, but it took the core concepts of the plot, retained those main themes and desires of the characters, and streamlined it into a solid horror movie.It's not only the character-versus-player dichotomy that causes issues though. Games are also unique in their pacing structure, as the participant has so much more control than in any other media. They have authority over the actions of the characters, in come cases even control over the path of the story itself. In cinema, viewer control comes (at most) from pressing pause, while the reader of a book can only control the text itself by reading at their own pace. In both cases, the core story, and all of its intricacies, isn't going to change.So, there are some subtle difference in terms of what makes a game or a movie fun. Games rely as much on reflexes or active thought as in sound and visual design or acting talent. For some gamers, their favourite moments within the medium come as prolonged shootouts in action games, a particularly fearsome puzzle to overcome, or a long, silent journey in a role-playing game. In short, games are an entirely different beast from the media that have come before them. In a way, it's as difficult to adapt a daydream to the cinema as it is a video game.

There is a serious difference in the ways that games and films think about plot, which may explain why so many video game adaptations fail from a story perspective. Mass Effect is seen as one of the best examples of strong video game story, but a lot of that framework comes from the lore of the universe itself. There is a flavor to Mass Effect that cannot easily be matched within a straightforward movie narrative, developed over information logs, dialogue options, and even by living in the game world for such a long time as a player. A movie adaptation would need to find a way to push that space epic into a smaller runtime, alongside finding a way to build its central, action-heavy story into a cohesive overall plot.

But even more straightforward, linear games would struggle. The previously-mentioned BioShock relies heavily on audio logs help frame the underwater city of horror that is Rapture, managing to combine the isolation of the player with overall world-building in a way that could not be managed easily within the framework of a film. Meanwhile, its central twisting reveal of the identity of the main character is so entwined with the notion of gaming control and choice that an equivalent reveal in a film would never have the same impact. Perhaps it's for the best that Gore Verbinski's film fell apart.

This is equally true of Assassin's Creed. Although even the most ardent of fan is unlikely to put any of the Assassin's Creed titles alongside BioShock in terms of storytelling, there's still a deep immersion to be found in Ubisoft's series. However, this is in part down to the framing of the Animus, the virtual reality machine that allows the core gameplay of Assassin's Creed to exist. Within the games, everything is a simulation, a fabrication two layers deep - a game within a game. Take that away from the unique medium of the video game and it loses its lustre.

This, of course, leads to one conclusion: to make a good video game movie, changes have to be made. However, choosing the right changes is a thin line to walk, and there are plenty of adaptations that differ heavily from their source material yet have changed entirely in the wrong way.

Perhaps the best case study of this phenomenon is 2008's Max Payne. On paper, Max Payne should have been an easy choice for a film adaptation. It had a decent action-noir plot in place already, with a tired undercover cop following a mystery with some genuine personal pain behind the story. On top of that, the game itself was built on set pieces that would not have felt out of place from a film itself. It should have been an easy win.

However, the changes made completely ruined any potential the film had. Bizarre tweaks were made to the core story, throwing what was already a good pastiche of the hard-boiled detective out of the window and replacing it with something unnecessarily convoluted. Max Payne retained the most difficult aspects of the game to adapt, and threw out the framework that should have turned it into a solid action movie.

Other movies have had the same problem, but in different ways. Warcraft has its fans, and it's easy to see why, as it manages to effectively set up the Warcraft world within its runtime. However, this focus on worldbuilding at whole is part of the reason why it didn't quite succeed, with many viewers coming away feeling that the film was overly bloated. Ironically, a Warcraft sequel would probably be a much more cohesive film, with the groundwork already completed.

Making a video game movie work takes brutal decision making, and potentially even a disconnect from sentimentality. Silent Hill might be one of the better video game movies, but even then the film may have been better suited by skipping the first game altogether and instead going to the more terrifying sequel, forgoing the convoluted explanation of what Silent Hill is and instead purely focusing on what the inscrutable location does.

Time and time again, cuts are made to make these films less difficult, sticking to the middle ground while maintaining those elements from the games that fail to work in a cinematic format. A prime example is Doom, which cut the demonic elements of the plot to make it more palatable while fumbling both action and horror and keeping its core character base as a squad of cookie cutter space marines. In effect, most video game movies fall into the same traps as David Lynch's Dune, retaining (and adding) the inexplicable while refusing to budge on elements that are detrimental to the film as a whole.

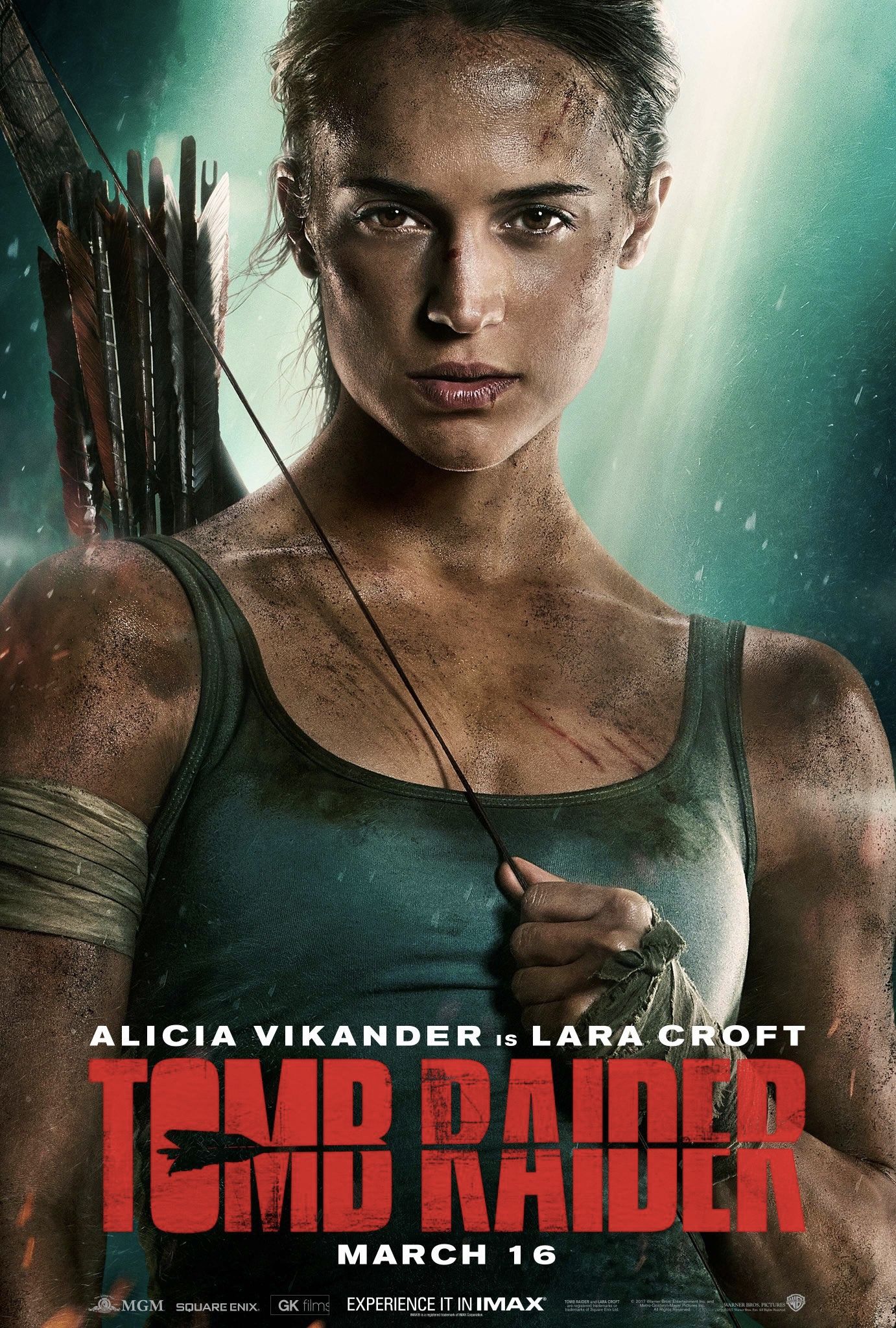

In spite of this, there's still a wealth of potential behind the Tomb Raider franchise. The recent reboots come closer to the Max Payne realm of thinking, an already-emotive story with strong characters and clear motivations in place. The 2013 release, fantastically written by Rhianna Pratchett, delivers a punch beyond many games of the same ilk, and in a manner that should ideally align itself well to a movie adaptation. The word 'cinematic' is thrown around too much in the video game sphere, but 2013's Tomb Raider and sequel Rise of the Tomb Raider certainly deserve it.

Indeed, the 2013 game itself led to criticisms over the difference between player action and the core plot, and this dissonance could lend itself well to film. Cut out the repetition of shooting villains with a bow and arrow, and instead focus on the turmoil, struggles, and victories of Lara Croft herself and there's the potential for a breathtaking thriller to be had. With Tomb Raiderdrawing inspiration from the last two games, it's ideally those impressive moments of great storytelling and gripping set pieces that shine through.

It won't be long before the dust settles on the film's release, and viewer opinion is able to be fully gauged. We will then be able to find out whether Tomb Raider has been able to avoid the pitfalls of the video game movie adaptation, or whether it will just be another name in the long list of disappointments. At the moment the critical reception has put it at the top of the video game movie pile, even if results have been mixed. Hopefully, Tomb Raider will be able to buck the trend, and instead provide a case study in exactly how video game movies can be done.

Next: Tomb Raider Isn't Really A œVideo Game Movie That's Why It's Good