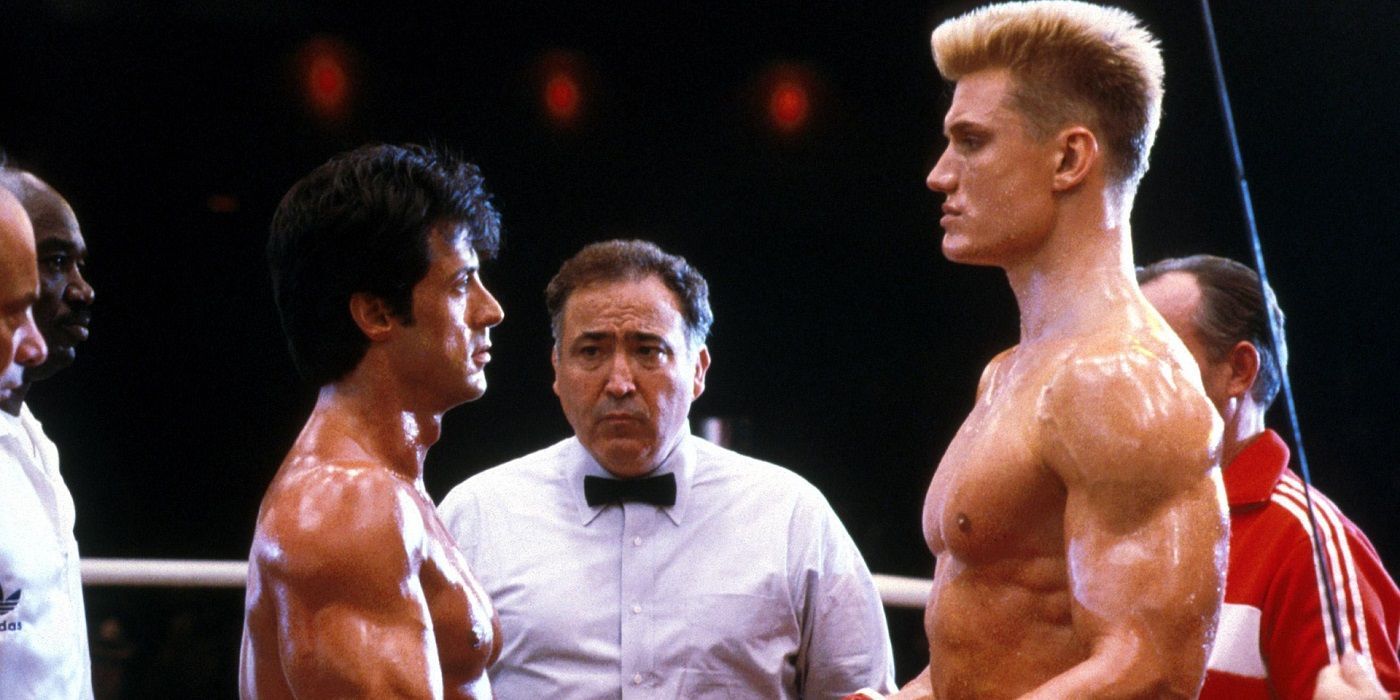

Take your midi-chlorians, emo Peter Parker and The Architect’s spiel – the worst jumping of the shark this side of the Fonz is Rocky IV. No single scene in particular either, but the whole movie. We open with Rocky gifting his brother-in-law a robot butler (happybirthdaypaulie) and things just become further removed from reality as we go. His former antagonist-cum-best friend is brutally killed in the ring by a 'roided-up Russian and the only way he can get out of his music video slump is to get revenge. Cue a barrage of pop-scored training montages where the Philadelphia Steps, the series’ enduring image, is replaced by Rocky climbing up a snow-covered mountain. Then, at the end, he somehow beats Dolph Lundgren’s Russian monster and single-handedly ends the Cold War. Not even metaphorically – in this world, Rocky Balboa basically brought down the Berlin Wall four years early.

Over the ten years prior to Rocky IV, Sylvester Stallone had made Rocky into a pillar of perseverance and the embodied heartbeat of Philadelphia - yet in just 91 minutes the writer-director-actor undid much of that, reducing the simple and relatable story of a Philly toughie going the distance into an over-the-top superhero adventure.

Rocky IV, of course, remains one of the most beloved entries in the series - and perhaps trashing it isn’t the best way to open an article celebrating the Italian Stallion’s fortieth anniversary. Indeed, it is in many ways what the series needed in 1985; the New Hollywood origins of the character were long-since dead and a simple good-versus-evil, broadly political, ultimately silly romp was what people wanted (and, based on its box office success, perhaps needed) in the mid-eighties.

But, love it or hate it, there’s no avoiding that Rocky IV trashes the internal logic and meaning to the franchise. Oh, there’d been garish touches in the previous sequels (especially once Rocky and Apollo Creed developed an unashamed '80s bromance), but this was where story was overtaken by style and the rounded formula forced into a stary hole. Floodgates opened, Rocky V made it even worse, breaking the already questionable timeline continuity (Rocky Jr. ages five years in the space of a couple of months) and telling a story that wouldn’t feel out of place in a daytime soap; with Rocky forsaking his son for street ruffian Tommy Gunn.

Rocky is an Oscar-winning great, an all-time, mass appeal classic that can still connect with modern audiences in spite of its rough 1970s edges - but Rocky IV & V left the franchise a laughing stock, tough to enjoy even ironically. How we got there, from a delicate masterpiece to lumbering kitsch, is a tale that rings across this era of cinema, joined by Superman, Jaws, Lethal Weapon and all your favourite slasher franchises. What makes Rocky stand out from those, however, is what it did next - executing what may just be the greatest retcon of all time. It didn’t explicitly change or overwrite events (like Superman Returns attempted to do); instead the series magically took two of the most “of their time” movies from the eighties and made them timeless.

The Retcon Part 1 - Rocky Balboa

Rocky was Stallone’s baby. Aside from starring, he wrote the first six movies and directed II, III, IV and Balboa. In fact, so much was his heart tied to the character that he chose to forgo a massive payday for his original script so he, then an unknown, could star. So, somewhat naturally, when Rocky V emerged as a widely-regarded artistic failure, he took it personally, stalling all development on the series for a decade-and-a-half.

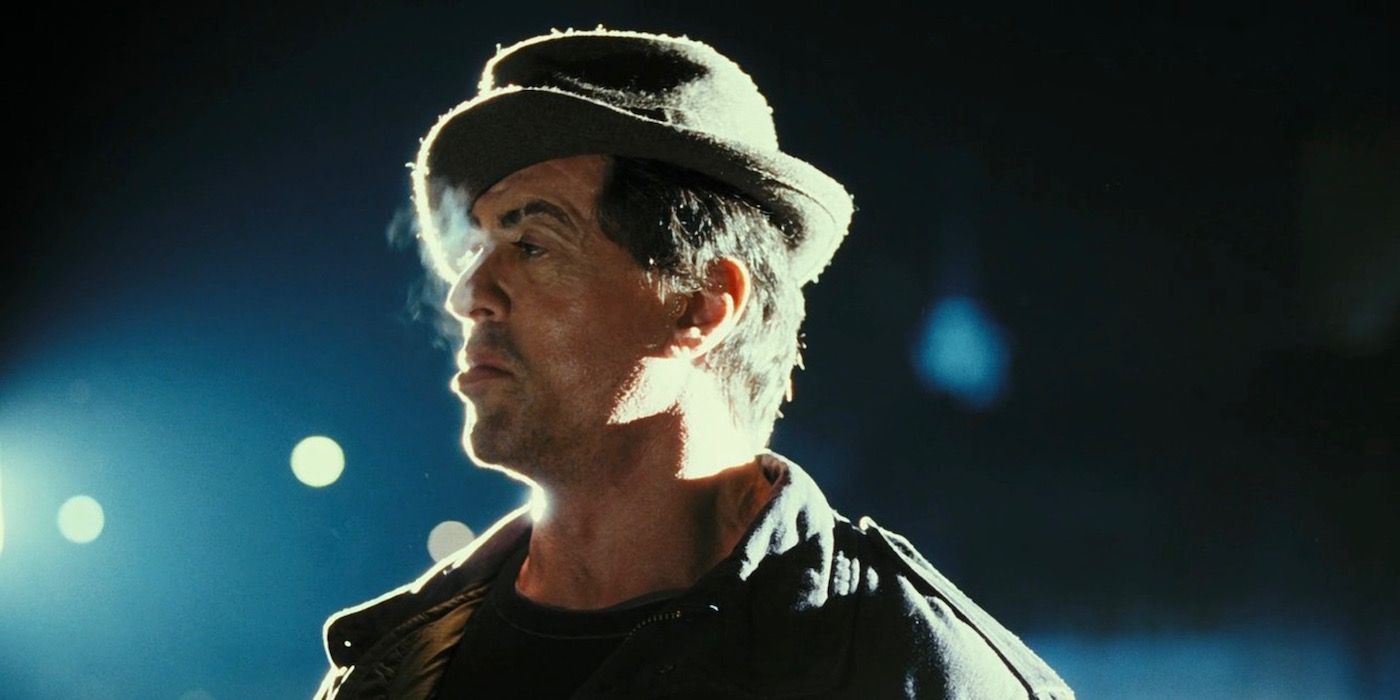

Rocky Balboa exists almost exclusively to correct that error. The Rocky movies had always followed similar plot beats and gone over the same territory, but Movie #6 is really a thematic remake and franchise-purpose meditation made before legacyquels were cool. We again have a retired Rocky, but this time it’s down to age, not forced trauma, and instead of moping, he’s now returning to the ring in an attempt to maintain his relevancy and prove he can still “go the distance”. Unsurprisingly, the ending loops back to the first movie, a wonderful ode to the joy of trying, rather than winning.

Essential to this is his fractured relationship with his son (now played by Milo Ventimiglia), and that’s where Balboa gets interesting; although there’s only glances at the actual events of Rocky V, this is Stallone fully addressing what he was trying to do in that film, showing the long-term impact on family life Rocky's career had. That distinguishes the movie, but, additionally, in dealing with the fifth movie's themes nostalgically, the disregarded Rocky V somehow feels more important. It may have not changed general opinion of the film, but you can come out of Balboa respecting Rocky V's part in the canon.

The Retcon Part 2 - Creed

That has nothing on what Creed did with Rocky IV, however. Ryan Coogler’s film was both a late-in-the-day sequel and a spin-off, moving away from Rocky to focus on Apollo Creed’s bastard son, Adonis (Michael B. Jordan). In many ways it’s an original movie just set in the Rocky universe, right down to there being no reprise of the classic full-screen title wipe (Stallone even stepped back from story duties), but the reverence it pays is staggering. Most notable is the handling of Rocky’s cancer diagnosis; a subplot that could have provided this movie’s "Han Solo moment" but instead is angled to once again be about “going the distance." However, the scope and ambition of Creed to correct the franchise is bigger than just one character.

Throughout the movie, events from every previous film are referenced, canonised, and injected with a feeling of sincerity: we find out who won the friendly knockabout fight between Apollo and Rocky at the end of Rocky III (because such unspoken details to a masculine friendship are no longer necessary); Rocky’s arc with his son is resolved in a carefully distanced manner that doesn't tread over Balboa's work; Mickey’s legacy stands tall and isn’t marred by his death coming from being thrown against a wall by Mr. T; the deceased Adrian and Paulie are remembered for their original backing of their partner and friend, not the two-dimensional characters they became in previous Rocky films.

Biggest of all, though, is the handling of Apollo’s death. Rocky IV shows it as a twinkly scored, strictly-edited beatdown that culminates in painful, super slo-motion fall; not the silliest part of the film, but the most troubled given its attempts at stirring real emotion. It would have been very easy for Creed to shirk it completely (like Balboa did Tommy Gunn), but instead the film uses it as the emotional backbone; the pure terror of dying in the ring haunts the slight Adonis and informs Rocky’s conflict over training him (in turn showing proper grief in a way that the "No Easy Way Out" sequence did not). The killer isn’t namechecked, so it’s not able to right the Cold War subtext beyond negating its presence; yet it’s so subtly handled that fans can dream-pitch a sequel where Adonis takes on Drago’s son in a revenge match and the idea doesn’t fly in the face of the grounded world that Creed returned the Rocky franchise to.

What Coogler did was a grander version of how Stallone dealt with Rocky V in Balboa: stripping the later movies of their eighties camp and bringing out the resonating emotion that underpins them, prompting direct reappraisal. He made bad feel good and silly feel smart.

Conclusion

Rocky was one of the biggest franchise of the 1970s and '80s, and while much of that came from the films' dependable structure and punch-flying escapism, what so connected with people from the very start and made the Italian Stallion so enduring was the story. Tonally the movies fluctuated wildly, and yet they ultimately told a heartwarming tale where the character remained true to himself. This was why the series remained so well regarded despite, up until 2006, having multiple entries that are (to say the least) less than well-regarded - from a distance, seeing Rocky develop, learning from his mistakes just as he finds new pressures was a narrative stronger than any poor storytelling could mar. Rocky Balboa and Creed didn't retell that four-decade-long journey, but they reframed it and allowed us to see that beauty unspoiled by contextual missteps.

Problems, of course, arise on rewatch when what should be highly emotional moments ring as cheap melodrama, and those problems still exist in the wake of Creed - but what Stallone and Coogler did was accept those failings and find the greater purpose underneath them. Apollo Creed’s death may be "dumb" as viewed in Rocky IV, but that doesn’t make the death itself or its impact intrinsically so.

For these reasons, the Rocky franchise is the ultimate example of “going the distance” - a movie series willing to embrace, not ignore, its mistakes to better the whole. The Rocky series is one of the most beloved stories ever realized with the medium of film, and it now really doesn't matter how iffy some of its presentation may have been.