The Academy Awards seeks to promote the film industry at its best, paying homage to the often unseen elements of labor required to make a movie. With the main ceremony, as well as the honorary and technical Oscars, the Academy’s objective is to acknowledge and reward every cog of the finely tuned machine that keeps Hollywood running.

Yet a number of blind spots remain. One of the industry’s most accomplished subsets of performers has fought for decades to be included amongst the awards categories with little progress on the horizon. Despite the obvious skill and high risk of stunt-work, the Academy remains hesitant to create a Best Stunts award to celebrate their efforts. Stunt man Jack Gill has been campaigning for inclusion in the awards since 1991. Last year, over a hundred stunt performers from throughout the industry protested outside the Academy's office in Beverly Hills, and gathered over 50,000 signatures on a petition demanding recognition during the awards. Sadly, little progress has been made.

Stunt work on film has a history as old as Hollywood itself. During the medium’s early years, out-of-work cowboys and circus performers would be hired to perform in chase scenes in Western serials, while carnival daredevils like Rodman Law, who made a name for himself parachuting off the Statue of Liberty, were brought in to drum up business. Vaudeville performer Helen Gibson was so successful as a stunt performer that she became the star of a short film serial called The Hazards of Helen, wherein she performed heroic feats like jumping from moving trains and leaping onto galloping horses mid-chase.

Stunt work became a full-time profession for many of these hired hands, and soon it became the domain of some of early Hollywood’s biggest stars, notably comedians like Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. Lloyd's masterpiece Safety Last! features not only one of the most iconic stunts in Hollywood history - where Lloyd hangs from a clock-tower - but is an early example of the industry taking stunt work seriously as something to replicate. Planning and safety devices became the norm and allowed directors to redo scenes with minimal down-time and reduced risk to life.

With the blockbuster age growing in the '60s and '70s, modern stunt technology allowed for greater spectacle, thanks to bullet squibs, air bags and more sophisticated wire work. Stunt men like Vic Armstrong and Bill Hickman rose to prominence in films such as Raiders of the Lost Ark and The French Connection. Audiences’ thirst for extravagant spectacle increased, and so did the stunts on offer, with stars like Jackie Chan making an impact with Western audiences thanks to scenes like the 100 foot-plus pole slide in Police Story.

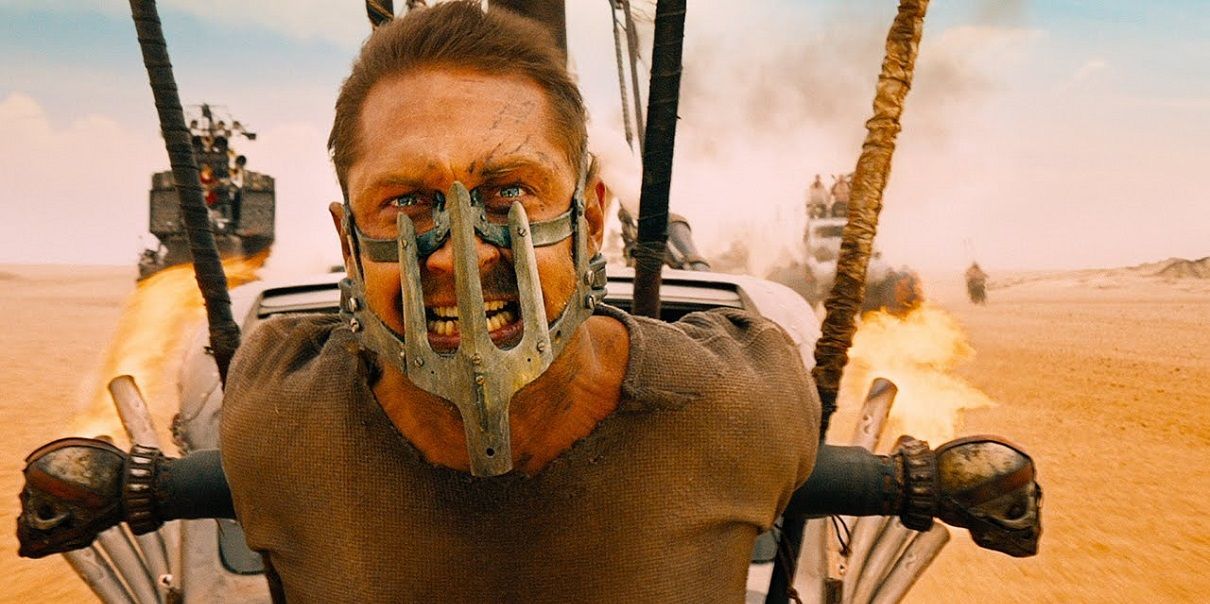

As blockbusters and high-octane thrill-fests remain the tent-poles of the modern industry, with expanded universes and multi-million dollar franchises springing up at every studio, the visibility of stunt-work is at an all-time high. 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road was praised for its use of practical effects and stunt men and women, and garnered ten Oscar nominations for its efforts, primarily in technical categories. Stunt workers are a crucial part of the ensemble in the Marvel universe as well as Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, the latter of which included a scene in The Dark Knight where a 16 wheeler semi-truck flipped 180 degrees with a stunt-man behind the wheel the entire time. Even major A-listers like Tom Cruise are keen to flex their muscles and commit to the kind of stunts that would make many a producer shudder in fear. Stunt-work plays a huge role in making the film experience authentic, yet the labour of it goes unrewarded.

The rise of CGI may play a part in stunt-workers’ struggle for acclaim. While computer generated effects offer a much safer experience for all involved, many audiences are turned off by the saturation of such visuals, no matter how realistic they are, and crave something ‘real’. There is a rising fear amongst stunt worker unions that such progress will put a lot of people out of work, which would be another good reason for the Academy to include a Best Stunt Work category: Increased visibility for the work would remind audiences of its worth in the industry.

Increased use of CGI has also diminished the continuing role stunt teams play on the biggest, most popular films of the year. The assumption remains that the death defying feats audiences are riveted by must be computer generated, even when they’re not. This Catch-22 situation puts film-makers and stunt teams in a trickier bind of trying to find a balance between computer generated and practical effects. Often, the answer is as simple as money: It’s just cheaper to animate someone in later.

Some in the industry are also hesitant to acknowledge the work stunt teams do in case it overshadows the big-name stars of the films. A similar argument erupted several years ago during the Oscar campaign for Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, which relied heavily on the impressive amount of ballet work star Natalie Portman did for the role, and the subsequent controversy after a dancer came forward to claim credit for the work. Film-making remains a collaborative effort, but as stunt worker Ben Bray noted, "I think simply the Academy still wants middle America to think that their heroes, the actors, are actually doing their own stunts."

Stunt workers have been rewarded in the past by the Academy but only in the honorary or technical Oscars, never the main show: Hal Needham, Vic Armstrong and Yakima Canutt all received awards over the past 50 years. Many of the problems regarding the lack of a major award from the Academy lie in industry politics. It has been argued that there aren’t enough performers in the Academy itself to constitute an entire category (around twenty performers have Academy membership). Given the Academy’s increased recent efforts to diversify its membership along lines of gender and race, it seems like a natural step to extend that to under-represented areas in the film industry.

The Screen Actors Guild have made great progress on this front by adding an award for Outstanding Performance by a Stunt Ensemble in both film and television, while the Taurus World Stunt Awards has been celebrating the best in the industry for many years now. Yet the Academy Awards remains the pinnacle of film achievement, and the exclusion of stunt work from its ensemble a shameful misstep. Stunt work is as crucial to the success of a major film as the acting or other technical aspects, and after decades of pioneering work that helped make Hollywood what it is, it’s time the stunt profession and its workers had their place in the industry, as well as film history, secured.