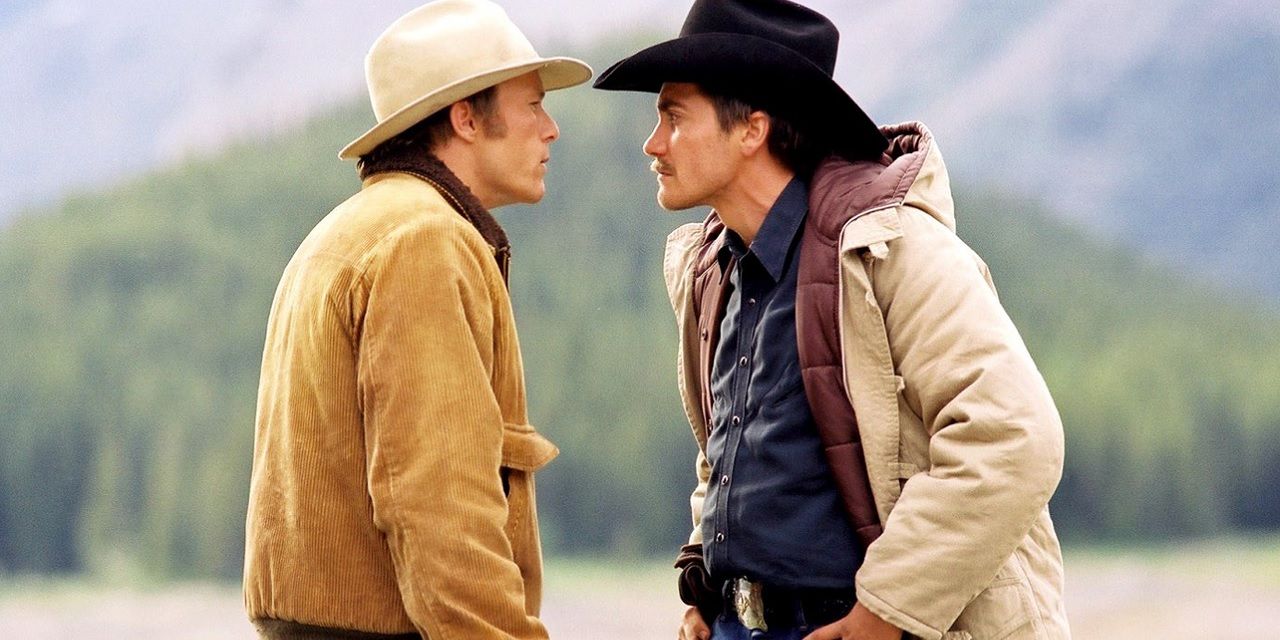

Low-budget indie hit Moonlight has garnered eight Oscar nominations this year and Chan-wook Park's The Handmaiden has been heaped with critical acclaim, yet these triumphs have only served to highlight a bigger gap in the market: where are all the gay romance movies? There have been a few significant queer titles in recent years, with Carol and Pride making strong showings, but the fact remains that since Brokeback Mountain became a critical darling and box office hit in 2005 (Ang Lee's romantic drama grossed more than $178 million worldwide, with a production budget of just $14 million) a genre that showed significant commercial and artistic promise has been left to gather dust. When gay romance ought to have been coming into its own in the mainstream, it all but disappeared.

The dearth of gay romance movies has been rendered less noticeable by the fact that representation has been on the rise in other ways. GLAAD's latest Studio Responsibility Index report found that, of 126 releases from major studios in 2015, 17.5% featured LGBT characters, while the organization's most recent Where We Are On TV report found that 4.8% of regular characters in scripted TV series are LGBT. But while LGBT characters are certainly present they rarely take center stage, and when they do their stories tend to be tragic rather than romantic.

Brokeback Mountain, of course, blended romance and tragedy, but most prominent LGBT characters lean heavily towards the latter: Colin Firth in A Single Man, Benedict Cumberbatch in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and The Imitation Game. While gay drama films have tackled important issues like homophobia and the AIDS crisis, none of it exactly screams ‘Valentine’s Day!’

Movies like Brokeback Mountain were aimed at a general audience (and perhaps even a specifically straight one), but in the 1990s and early 2000s a significant subgenre and its attendant rack at movie rental stores catered expressly to queer audiences with titles like Jeffrey (1995), But I’m a Cheerleader (1999) and Mambo Italiano (1993). This era produced a significant body of queer romantic comedies - some mediocre and some charming. There was some crossover appeal for straight audiences, but who these movies were ‘for’ wasn’t up for debate.

Touch of Pink (2004) was, like Mambo, interested in the intersections of immigration issues, queerness and families: My Beautiful Laundrette meets Clueless. Several of these movies are quite playful in their narrative structures and fourth-wall breaking. In Touch of Pink the protagonist speaks frequently to either the legitimate ghost of old-Hollywood actor Cary Grant or an imaginary friend in the shape thereof. Billy's Hollywood Screen Kiss (1998) is filled with fantasy sequences, songs, and fourth-wall-breaking asides. The Birdcage, a 1996 remake of the 1978 film La Cage aux Folles (itself based on the 1973 play) is fully in this spirit and tradition, and did exceptionally well with general audiences while addressing a gay core demographic. Even in the midst of the AIDS crisis, movies like Jeffrey both looked at HIV head-on and worked as buoyant, joyful romances: sex and love and joie de vivre against the threat of personal danger and communal oblivion.

This vibrant subgenre has almost vanished. In part this is because Hollywood stopped making any romcoms. The star-vehicles of Julia Roberts and company collapsed and, rather than innovate with the format, studios (including smaller studios and the indie branches of bigger companies) moved on. Hollywood could circle back to the romcom, but in a market now dominated by tent-pole franchise movies, is there a commercial reason for them to do so?

There are certainly neglected audiences and neglected needs. The sheer hunger for the Fifty Shades instalments ought to indicate that there are people (mostly, though not entirely, women) out there in the world who just want to watch a romance movie - any romance movie. But for all the talk of the bottom line, studios are often less interested in what audiences want than in what they think audiences want.

This same wariness can also be seen in the resistance to female or black-led projects. Selma director Ava Duvernay has noted that "studios aren’t lining up to make films about black protagonists," yet Theodore Melfi's true-life drama Hidden Figures - which features a trio of black female protagonists - has so far grossed more than $144 million worldwide. If Brokeback Mountain and The Birdcage performed so well ten and twenty years ago, respectively, does that not suggest that similarly-positioned films (about gay people rather than about gayness as angst) might do as well (or even better) now?

There's a lesson to be learned from the successes of titles as diverse as The Handmaiden, Hidden Figures and, yes, even Fifty Shades. There is a gap in the market for gay romcoms that capture the energy and fun of the '90s boom - the only question is, which studio will be smart enough to capitalize on it first?