NOTE: The following post contains potential SPOILERS for season 1 of Mr. Robot

Sam Esmail's hacker drama Mr. Robot has been something of a surprise gem to help close out the summer on USA. The Fight Club-esque drama stars Rami Malek as Elliot Alderson, a technical expert who holds a security firm job, providing aid to a massive global corporation whom he secretly despises. Too socially awkward to interact with other people in normal ways, Elliot gets to know his friends, co-workers, and even his therapist by hacking into their personal accounts and extracting all the juicy and terrible details of their private lives - from how much debt they're in to what kind of porn they watch.

Elliot's mental health issues make him the quintessential unreliable narrator, most prominently evidenced by the fact that any time someone mentions fictional conglomerate E Corp, the audience hears it as "Evil Corp" - Elliot's pet name for the company. This simple quirk, by driving home the point that what Elliot sees and hears may not match up with the "reality" of the world he lives in, is just one of the ways that Mr. Robot's twist was telegraphed throughout its first season.

The other most notable quirk of Elliot's personality is his tendency to speak - sometimes in voiceover and sometimes looking directly at the camera - to the viewer. It's reminiscent of Frank Underwood's sly asides and glances at the camera in House of Cards, but where Frank cultivated an almost chummy relationship with his audience, Elliot treats his confidant - referred to only as "you" or as his "imaginary friend" - with varying degrees of neediness, desperation and distrust. Whenever Elliot discovers some hugely important fact that he blocked from his own memory, he demands to know if "you" knew about already.

This has widely been referred to as a case of Mr. Robot breaking the fourth wall, but this seems like an overly simplistic way of describing Elliot's relationship with the viewer - if it even is the viewer that he's speaking to. Outside of a subtle reference from Mr. Robot (Christian Slater) in the Season 1 finale, claiming that the world they live in has lost all sense of reality, Elliot never seems to show any awareness that he's a character in a TV show. This is not Community, and Elliot is not Abed.

The second-person narrative voice is a long-standing technique in literature, and a particular favorite of Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk. Indeed, much of Fight Club is written in the second person and some of this bleeds through into David Fincher's film adaptation ("You wake up at SeaTac, SFO, LAX... This is your life, and it's ending one minute at a time.") This is relevant because the influence of Fight Club in Mr. Robot is very transparent, and was acknowledged by Esmail himself in an interview with EW.

The roots of the term "fourth wall" come from stage theater, where a typical box set would have three physical walls with the proscenium acting as an invisible fourth wall. The expression "breaking the fourth wall" originates from the act of a character looking directly at the audience - an act that, when done accidentally in filmmaking, is called "spiking the camera" and can instantly ruin a take, because it breaks the illusion that actors are not aware of their audience.

Yet just because this technique is what coined the term, it doesn't necessarily follow that every instance of a character looking directly into the lens or apparently addressing the audience breaks the fourth wall. The phrase has long since evolved beyond its literal meaning. Just because a character uses the pronoun "you," it doesn't always mean that they're actually talking to you.

In the case of Mr Robot, Elliot addressing the audience as though they were his imaginary friend doesn't seem to be an act of breaking the fourth wall, but rather of casting the viewer into the role of an additional character on the show, seen only by Elliot himself. Perhaps the closest comparable example of this is not in another TV show or even another movie, but in a video game.

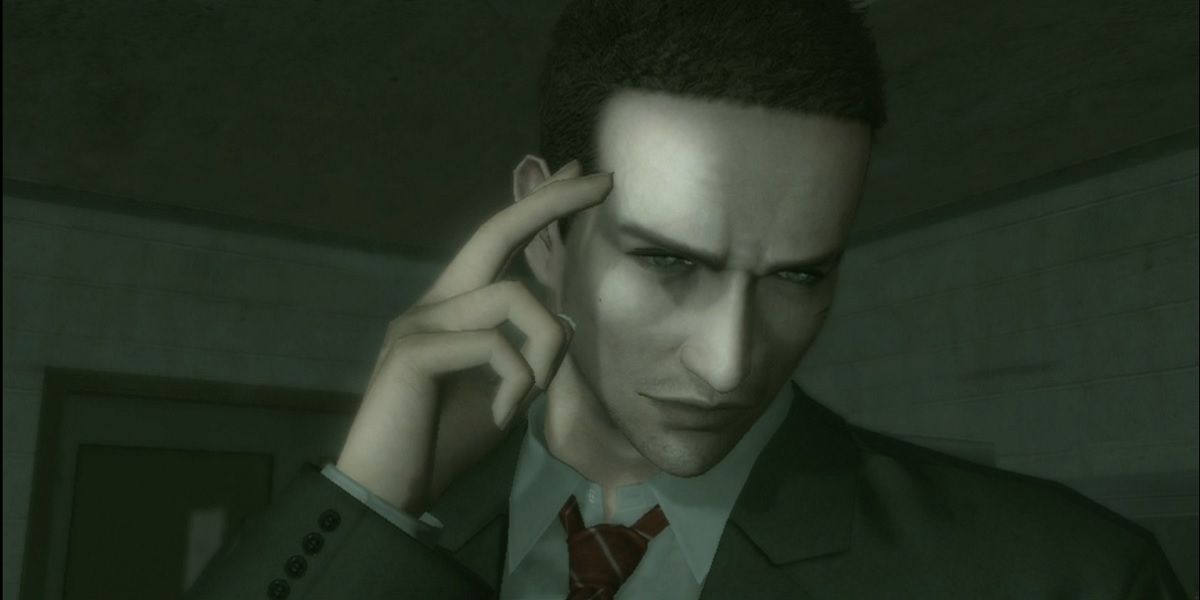

Hidetaka "SWERY" Suehiro's joyfully bizarre 2010 game Deadly Premonition is essentially a playable version of David Lynch's classic mystery series Twin Peaks, with the player taking on the part of an FBI agent who is called to a small logging town to investigate the murder of a young woman. After the player is first introduced to Special Agent Francis York Morgan, they are greeted with a black screen and the query, "Zach, can you hear me?" The player is then prompted to respond by pressing a button, thereby casting themselves as Zach, who is apparently York's imaginary friend. York continues to address Zach - and, by extension, the player - in this manner throughout the game.

Speaking directly to the audience in this way does not break the fourth wall in a traditional sense, but rather seems to be enforcing a form of audience participation. Elliot never expresses an awareness that he is a character in a television show, and neither does Frank Underwood. The characters address the viewer not as someone who is watching a fictional narrative, but as a confidant and friend.

This technique is profoundly effective, because it casts the audience in a fixed role within the ongoing drama. In House of Cards, the viewer is forced to be complicit in Frank's underhanded scheming, becoming an unwilling accomplice to his actions. "Did you think I'd forgotten you?" Frank asks, shortly after murdering a character in cold blood, sharing a chilling glance with the audience while looking in a mirror. "Perhaps you hoped I had."

In Mr. Robot the effect is somewhat different. Rather than using the audience as a sounding board for his thoughts, Elliot demands responses that cannot be given. "Are you freaking out?" he queries desperately, in the midst of a freak-out of his own. "Tell me the truth. Were you in on this the whole time?" If Frank Underwood is the acquaintance that the viewer would rather be rid of, then Elliot is the friend that they want to help, but cannot.

Breaking the fourth wall is commonly used for comic relief, reminding the audience that none of this is actually real, so they shouldn't worry too much about the outcome. In Mr. Robot, however, the camera-spiking and second person narrative are employed to forcibly pluck the viewer from the position of a spectator into that of a participant. Instead of creating distance from the drama, it makes Elliot's struggle feel all too uncomfortably close.

MORE: Mr. Robot: Is Elliot A Hero?

Mr Robot Season 2 will premiere on USA in 2016.