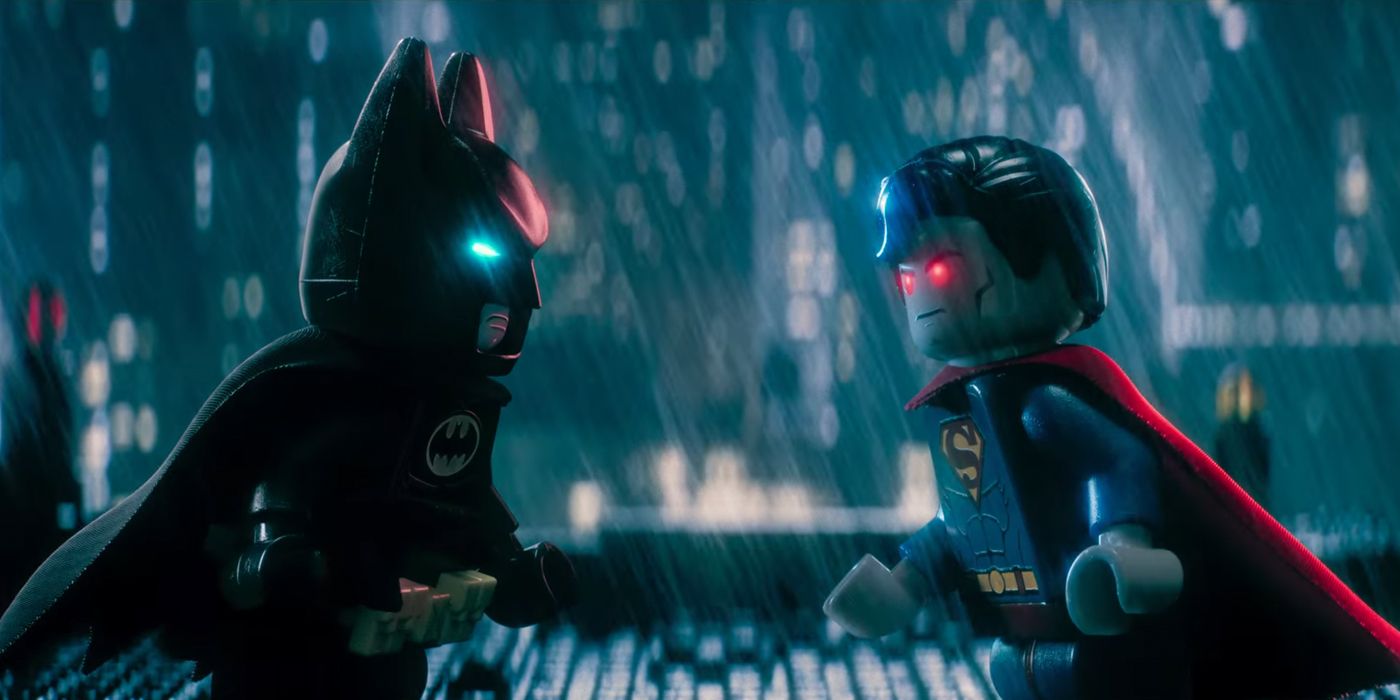

He may be deserving of credit for helping to build, and keeping afloat the comic book titan DC Comics, but these days, the pop culture conversation surrounding Batman is complicated, to say the least. Which makes it even better news that The LEGO Batman Movie has gained such critical buzz and fan excitement, pitting the Dark Knight against some of his most iconic comic book villains (with help from some equally-iconic allies). And the timing couldn't be better.

As DC Comics fans and critics are discussing what future, if any can be found in the version of Bruce Wayne portrayed by Ben Affleck in the DC Extended Universe, some will claim that this lighthearted, free-wheeling hero is the comedic alternative we really need. While that may be true, there's a significant difference between the two. It's the same reason that LEGO Batman leaves crowds smiling, and the DCEU has a different emotion in mind. Fans are guaranteed to have their preference, but before anyone claims that one approach to Batman is "better," they should first understand why they feel that way to begin with.

It's All a Question of Camp

It is not our intention, nor, likely, within our ability to deliver readers a complete, well-rounded sense of Camp or the pursuit of such - it is as difficult an intellectual endeavor to define as it is to execute. But we believe that in grappling with some of the tenets of the sensibility, movie fans can gain a better sense of why the LEGO Batman hero is more resonant, or seems more faithful, to their own notion of Batman put forward in Zack Snyder's Batman V Superman. Or, failing that, perhaps understand why their preferences in comic book movies tend towards one of DC's competing studios.

The simplest way to define camp as a concept in action is delighting in excess, exaggeration, and an 'over-the-top' mindset with the intention of amusing the audience. One of the most common TV shows described as camp is the original Batman series of the 1960s, starring Adam West (which LEGO Batman may most closely resemble in terms of sensibility or tone). The fact that villains dressed in multicolored bodysuits menaced the innocent with boulder-sized bombs is a simple illustration of going beyond the limits of reason for a laugh, but the show succeeded by placing the characters inside a world where such things were, if not commonplace, then feasible. And never taken as a joke.

The show may have been ridiculous in premise and plotting, but so were the comics of the day.

One need only look at the final act of The LEGO Batman Movie to see how the advancement of technology, and the escalation of just what constitutes 'over the top' or 'too much action' in the modern moviegoer. Godzilla may terrorize the harbor, the Eye of Sauron may scan the city, and Voldemort may cast spells upon the innocent, but the characters themselves never break the fourth wall by observing how absolutely insane and impossible this sequence of events really is. To them, it's a problem to be solved without comment - and the audience finds it all more amusing as a result.

To be clear, a movie succeeding in the pursuit of pure, unwavering camp doesn't necessarily qualify as 'good,' or satisfying to all viewers (taste can vary wildly). And by contrast, a movie isn't 'bad' if it attempts camp and fails, or pursues a camp aesthetic only where it likes. But the basic rules are followed by most films and TV shows that deliver impressive, ambitious action sequences or conflicts that a) treat it as simply another hurdle to overcome, and b) never comment on the absurdity of the hurdle since, to those in the story, there's no such thing.

For demonstration, the Marvel films embraced the inherent camp of the comic book source material, despite the less 'believable' aspects. The story of Iron Man was surprisingly modern and grounded, yet the fantastic was still deemed plausible in the film's universe. As a result, the final showdown including Jeff Bridges in a cartoonish, mech-like suit of armor wasn't as jarring or absurd as it otherwise would have been. The movies play the camp comics straight, and satisfy. Just imagine how strange it would seem for Steve Rogers to break the camp, and note to Peggy that Red Skull's face looks absolutely insane and silly.

The Batman Movies Demonstrate The Danger

The Batman movie series alone has demonstrated just how difficult it is to execute camp in any heightened fashion, and still find box office success. Director Tim Burton proved that "dark" doesn't need to mean the same thing as "serious," depicting a version of the Batman world that was still as off-the-wall and larger than life, but anchored Bruce Wayne in a darker archetype. To be fair, Jack Nicholson's 'Joker' may be to thank for the film's overwhelming sense of camp, ensuring that no matter how dark or how human the story attempted to be, the film itself was meant to amuse with its absurdity and excess.

Things went astray with the sequel, Batman Returns. There were still elements to enjoy and applaud, and most of them were remnants of the previous film's approach to absurdist amusement. Catwoman can become a feline sexpot... just because. And attacks from costumed rioters (and the gadgets Batman uses to stop them) don't even raise an eyebrow. But the trend towards darkness, and the tricky nature of camp were spotlighted by Burton's deformed, disgusting Penguin (played by Danny DeVito).

Had the characters of his Gotham City still been blissfully oblivious to his unsettling appearance and personality, the audience might have found humor in the grotesque insanity of it all. But Cobblepot was a step beyond normal even for them... and audiences (along with the studio's accountants) didn't find it amusing.

While Batman Forever may be looked upon as a disaster these days, its effectiveness in recapturing some of the camp, resulting in a family-friendly romp paid dividends, out-grossing Returns and receiving mixed/average reviews. It still wasn't the direction that mass audiences found inspired or promising, but it at least attempted to bring back the insane villains and impossible capers (and a Robin, too!). Director Joel Schumacher even accented the original, homoerotic roots of camp as an artform by accentuating the muscles, nipples, and backside of the hero to amp up the amusement.

But it was Forever, and largely Batman & Robin's erasing the 'play it straight' mentality of the heroes that drove into self-aware self-parody and intentional camp that eroded the entire reason it worked in the first place. Forever may not be 'good,' but camp made it something with purpose. And following the failure of Batman & Robin, the studio didn't know what to try next. Camp was killed, which meant it fell to Christopher Nolan to try something truly ridiculous: take Batman seriously.

It may seem like an obvious decision now, but the fun, exaggerated thrills, and the entertainment value (and success) of LEGO Batman should higlight just how risky it was to step away from the campy comics that had shaped the Dark Knight's image in the public eye. Yet Nolan committed, casting off all signs of camp. There may be humor in this world, but the premise was anchored in real people, experiencing real development, and fueled by real, serious doubts and pain. The fact that a man dresses up as a bat to fight criminals is called out for being ludicrous and strange, and Bruce Wayne relies on practical science to tackle street level problems.

Batman Begins proved that the concept of a Batman existing in our world had potential, even if it strayed from the tone and letter of the comic book source material that fueled "Bat-mania." Instead, it pursued the same path that modern comic book writers like Frank Miller had done years earlier: it attempted to re-imagine, re-contextualize, and modernize the idea of Batman to make him relevant to today's world - not existing apart from it, as a means of escapist entertainment. And The Dark Knight showed that what modern audiences craved from comic book superheroes was rapidly changing.

Over one decade and countless 'serious' superhero movies later, the release of The LEGO Batman Movie shows the pendulum of pop culture tastes in full swing. It isn't that one interpretation of Batman, Joker, Barbara Gordon, or Robin is inherently 'better' or 'more faithful' than any other which defines how satisfying it is (at least not entirely). Camp is fun for a reason, but the credit goes to the filmmakers for capturing it so deftly. In the process, they remind audiences why the Batman comics of the Silver Age were still entertaining to read, and the Adam West series a fun world to visit.

That being said, Batman didn't survive - nor DC along with him - because the writers stuck to style over substance.

Why The DCEU is a Different Story

It should be obvious by now that "camp" is almost always synonymous with "fun" in the world of comic book superheroes, in the sense of escapist, absurd, comedic satisfaction. Or, perhaps, more accurately, stands opposed to dark, serious, character-focused drama (that may not need to be the case, but in practice it's become a clear delineation). That means that the world of the DCEU established by Zack Snyder - not necessarily identical to our own, but meant to be taken as such - is almost impossible to qualify as camp in any sense. A Batman who is resolute, heroic, improbably-gifted with skills or technology, and facing villains in over-the-top costumes may be entertaining, but it's not something the DCEU can include.

The decision made by Snyder to abandon campiness isn't all that different from Nolan's, but Snyder has taken a more easily traceable influence from modern Batman comics. The modern comics that asked timely, socially relevant questions, and distinctly gained popularity because they attempted to do something other than simply entertain. Again, it bears repeating: one ambition isn't any better than the other, since executing camp is, as we've shown, incredibly hard. And entertaining and amusing audiences by escalating action and spectacle without breaking the tone is an art to itself. Mainly because camp itself is so hard to define, and therefore so hard to follow.

In fact, one of the first and most influential attempts to describe, refine, and define 'Camp' was done by Susan Sontag in 1964 in "Notes on Camp," and essay that began her ascent to becoming one of the most influential critics of the decade. In her groundbreaking efforts to define camp, and thereby investigate how and why it amuses audiences, she singled out two distinct points (among countless others) relevant to the budding DCEU. Primarily, what she would have to say about the ability for Snyder's superheroes to entertain and amuse while pursuing contemporary issues, and complicated characters:

What Camp taste responds to is "instant character" (this is, of course, very 18th century); and, conversely, what it is not stirred by is the sense of the development of character. Character is understood as a state of continual incandescence - a person being one, very intense thing. This attitude toward character is a key element... it helps account for the fact that opera and ballet are experienced as such rich treasures of Camp, for neither of these forms can easily do justice to the complexity of human nature. Wherever there is development of character, Camp is reduced.

Time has a great deal to do with it. Time may enhance what seems simply dogged or lacking in fantasy now because we are too close to it, because it resembles too closely our own everyday fantasies, the fantastic nature of which we don't perceive. We are better able to enjoy a fantasy as fantasy when it is not our own... This is why so many of the objects prized by Camp taste are old-fashioned... It's not a love of the old as such. It's simply that the process of aging or deterioration provides the necessary detachment -- or arouses a necessary sympathy. When the theme is important, and contemporary, the failure of a work of art may make us indignant. Time can change that. Time liberates the work of art from moral relevance, delivering it over to the Camp sensibility.

As complicated as those thoughts may be, comic book movie fans see them in practice everywhere. Captain America and Batman should be equally impressive heroes, but with Cap's unified, resolute character based in WWII, and rendered 'old fashioned,' he's a hero almost impossible not to admire (while finding completely amusing for his anachronistic personality). And with Zack Snyder's Batman shaped by themes of xenophobia, extremism, and security - themes reflecting the world we live in today - audiences aren't allowed to escape, but forced to choose sides, and free to take (completely justified) personal offense to his characterization on moral, ethical, or artistic grounds.

It's also no coincidence that Captain America: The Winter Soldier, the film which focused intently on the changing character dynamics between Steve Roger and Bucky Barnes, was seen as arguably Marvel's best film to date. Or that Iron Man, a film also rooted firmly in Tony Stark's journey from arms dealer to superhero receives the same recognition. Or, on the opposite side, why movies like Iron Man 2, Suicide Squad, and Thor: The Dark World tried to deliver both escapist superhero action and character development, and were judged more harshly.

Movie fans, like comics fans, shouldn't even need to say that they enjoy camp, since it's essentially stating that the reason you love superheroes is the same reason they became such a phenomenon in the first place. And the success, critical approval, fan support, and soaring spectacle of the Marvel Cinematic Universe - along with The LEGO Batman Movie - shows that audiences are as pleased as ever to enjoy well-executed camp (or simply well enough, and with some 'darkness' added to increase the substance). But to expect the same from the DCEU, having so clearly established that their ambitions lie in areas that exclude entertainment and satisfaction of camp, is a recipe for disappointment.

At an early point, Zack Snyder, like Christopher Nolan before him, decided that pursuing a path of more complicated, deconstructionist character work and themes that may make today's audiences ask uncomfortable questions was preferable. Since audiences are able to enjoy or ignore each kind of superhero or comic book film as they please, it's hard to argue that all films pursuing camp is a better route. But it also means that delivering successful films is a new kind of challenge for the DCEU.

One might look at Suicide Squad as a case of the studio unable to make up its mind, wanting to adapt an inherently camp property with absurd characters and villains while still keeping it grounded, and relevant. Had it been either more escapist and fun, or more grounded and less absurd, it could have been more successful. The same goes for Justice League, the film promised to bring a more hopeful attitude to the DCEU. Should it attempt to remain contemporary and character-oriented while also pursuing comic book-esque action or spectacle, it, too, may be in for trouble.

-

It's entirely possible, and completely understandable for DC Comics fans to leave the theater claiming that The LEGO Batman is their preferred version of the Dark Knight, or, if they're feeling bold, a superior one to the DCEU. But in the eyes of camp, at least, they're pursuing two mutually exclusive goals. It's far from an exact science, and the two versions of the iconic character may succeed or fail completely on their own merits, regardless of those goals. In the end, fans should probably just be glad they're being given a choice.