This month marks the 30th anniversary of Watchmen, the groundbreaking 12 issue DC Comics series from writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons. It’s amazing that a comic book series that premiered all the way back in 1986 still feels as omnipresent and relevant today. It helped reshaped the comics industry in its image, and still invites exploration of its dense themes of philosophy and symbolism. The iconic series has inspired countless other comics, television shows, books and movies (including its own 2009 cinematic adaptation), and its influence continues to felt throughout the entertainment industry.

Given it's existed for three decades and has reaped a whirlwind of hype and critical acclaim, its become easy to take Watchmen for granted. But it’s still worth noting just how revolutionary Moore’s subversive vision and Gibbon’s artistic ingenuity truly are, as they still reverberate in 21st century pop-culture. With that in mind, here are 15 reasons why Watchmen still endures, how it redefined superheroes, and why it became so influential.

15. Superheroes Deconstructed

Moore’s original vision for the series was a self-contained storyline incorporating DC’s purchase of characters from Charlton Comics, namely The Question, Blue Beetle, Peacemaker, Nightshade, Peter Cannon Thunderbolt and Captain Atom.

Moore’s initial storyline centered on the murder of The Peacemaker. But things changed after he was told DC was planning on introducing the newly acquired characters into the DC Universe via their 1985 continuity housecleaning Crisis On Infinite Earth storyline). Rather than scrap the plot, Moore simply made up his own characters based on the Charlton archetypes, and Watchmen was born.

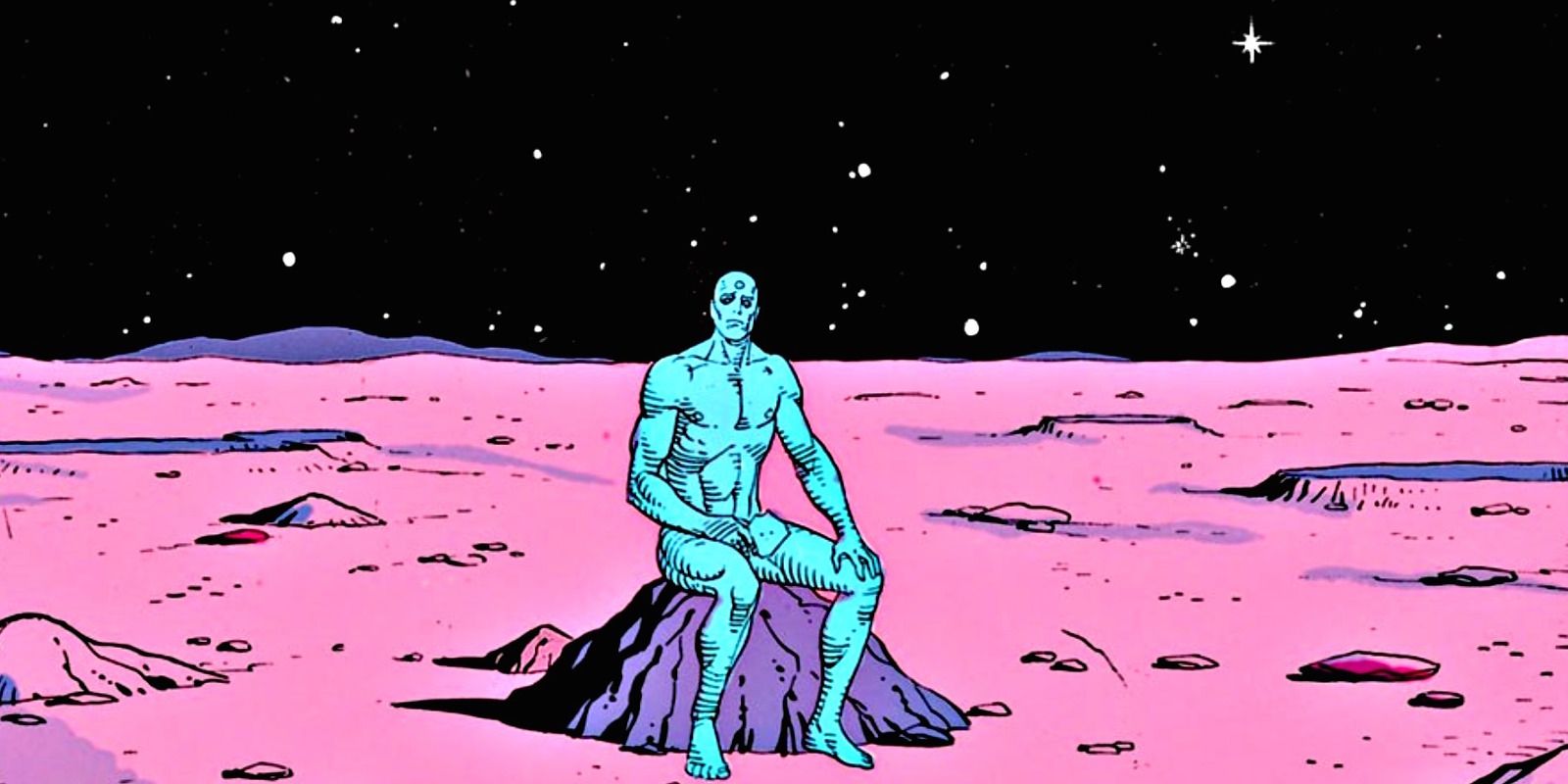

This creative decision freed Moore to deconstruct superheroes in a way never attempted in mainstream comics (which also acted as meta-commentary of comic book tropes). Insecure, deeply flawed, sexually dysfunctional, sociopathic, and neurotic, the Watchmen were brooding anti-heroes moved to fight crime less by altruism than by their own questionable egocentric motivations. And Dr. Manhattan (the series' only truly super-powered character) showed the destructive capabilities a superhuman would pose for the human race, inspiring fear over hero-worship. For (arguably) the first time in the comic book medium, Moore showed how the real world would react and be shaped by superheroes, and the results were anything but pretty.

14. The Rise of Grim and Gritty

1986 saw the rise of two seminal comic miniseries: Watchmen and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns. Although both were conceived independently, it’s amazing how complimentary and symbiotic they are in mood and structure. Where Moore deconstructed basic superhero archetypes, Miller deconstructed Batman himself, and both stories took place in urban dystopias threatened by Armageddon.

The combined one-two punch of Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns was so kinetic that it knocked the graphic storytelling medium off its axis. In the shadow of Watchmen comics, as a whole grew darker; previously established upbeat characters grew more conflicted, more brooding, more violent. The line between good and evil was more blurred than ever.

For some comic traditionalists, this proved to be a rude awakening. Even Moore and Gibbons would grow to be frustrated that their self-contained tale would snuff the escapist joy out of comics in its wake. But every medium most adapt or die. Grim and gritty became popular for a reason, reflecting an angst triggered by the rise in violent crime and the worries of the arms race with Russia. It fit the mood of the times, for better or worse.

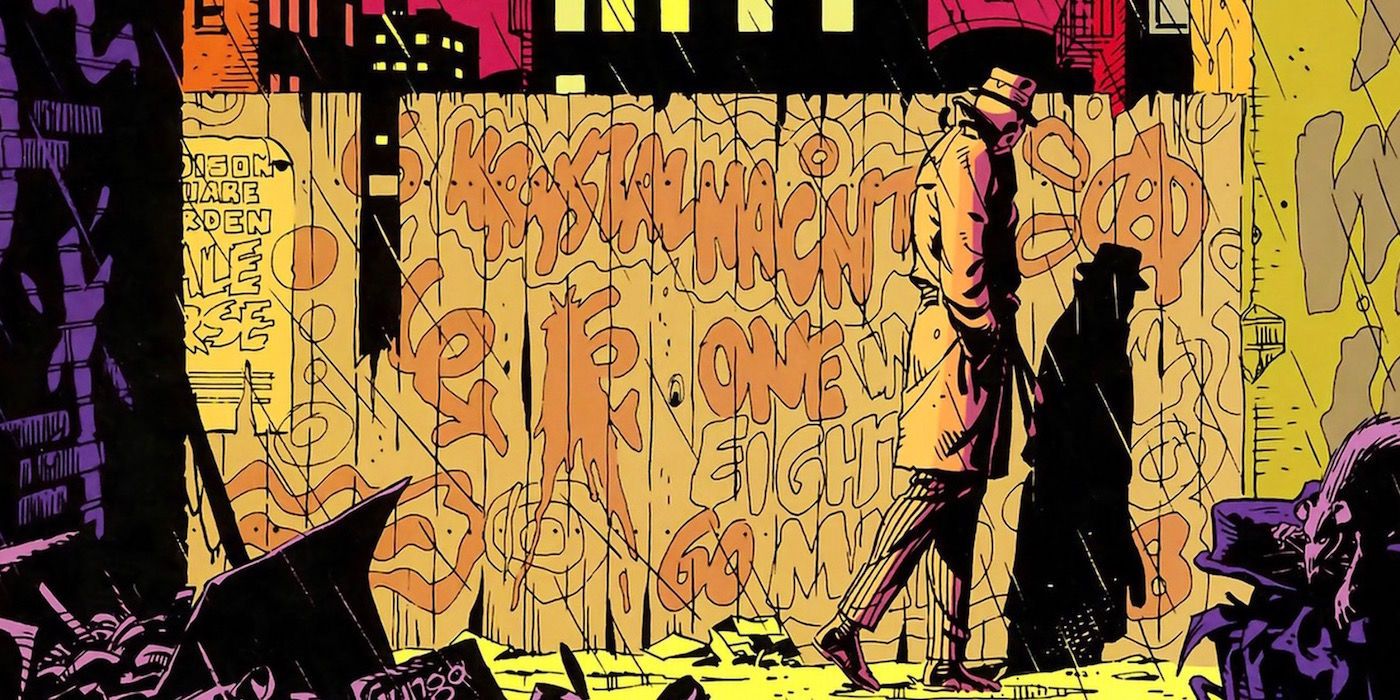

13. Rorschach

A homophobic, violent sociopath fond of breaking criminals' fingers and dropping them down elevator shafts, Rorschach was the most overtly unpleasant character in Watchmen. But he became the readers' favorite nonetheless.

Moore fashioned the character after The Question, but he also threw in a bit of Mr. A (get it?) from witzend comics (get it??) as well. Both characters were created by comic legend Steve Ditko and were imbued with his objectivist ideals. Moore actually mocked Ditko’s fondness for objectivist author/philosopher Ayn Rand, however, by attempting to make the masked vigilante’s worldview as detestable as possible.

Moore was unnerved with Rorschach’s popularity and his impact on comic culture. He elaborated on his disgust in an interview, saying that in real life, a masked vigilante, “wouldn’t have time for a girlfriend, friends, a social life, because he’d just be driven by getting revenge against criminals…he’d probably smell…wouldn’t talk to many people…I meant him to be a bad example, but I have people come up to me in the street saying, ‘I am Rorschach! That is my story!’ And I’ll be thinking, ‘Yeah, great, can you just keep away from me and never come anywhere near me again for as long as I live?’”

12. Sex and Violence

Graphic sex and violence are nothing new in the comic book world. The E.C. horror comics of the 1950s were deemed so perverse in this regard that it sparked a level of moral outrage from authority figures that almost killed the industry altogether. Likewise, independent comics from the likes of R. Crumb were stuffed full of sexual content. But by the 1980s, DC and Marvel Comics predominantly produced kid-friendly material, even using a comics code that forbid anything too risqué or bloody.

Watchmen was the opposite of kid-friendly, and it even went beyond The Dark Knight Returns in terms of graphic violence and sexuality, from millions of dead New Yorkers, to Rorschach slaughtering two dogs, to the disturbing rape scene with the Comedian attacking Sally Jupiter. These unforgiving images drove home the point that Watchmen was not “kid’s stuff” and created a level of controversy that cemented its provocative reputation as a game-changer for the medium.

11. Cold War Commentary

One of the most unusual elements of Watchmen is the world in which it was set. While the comic mirrored the '80s with anxieties over the nuclear arms race between America and Russia, Ronald Reagan wasn’t America's president. Instead it was Richard Nixon, held in power (seemingly without term limits) thanks to the use of the Minutemen (and later) the Watchmen, who helped the U.S. win the Vietnam War. Electric cars are the transportation of choice. Things are the same in many ways, and the majority of the comic world's differences can be directly attributed to the longstanding presence of superheroes.

While Moore has never gone into deep detail regarding his decision to place Watchmen in an alternate universe, he theorized that it "perhaps gives the American readership a chance in some ways to see their own culture as an outsider would."

This technique also differentiates Watchmen from the DC Universe and has helped in its timeless appeal. But even though it exists in a different world, the threat of nuclear war was a terrifying reality in 1986. Moore’s story showed the inherent absurdity of mutual mass destruction, and it remains a potent reminder about the dangers of self-created apocalypse, one that is still disturbingly plausible.

10. The Visual Aesthetic

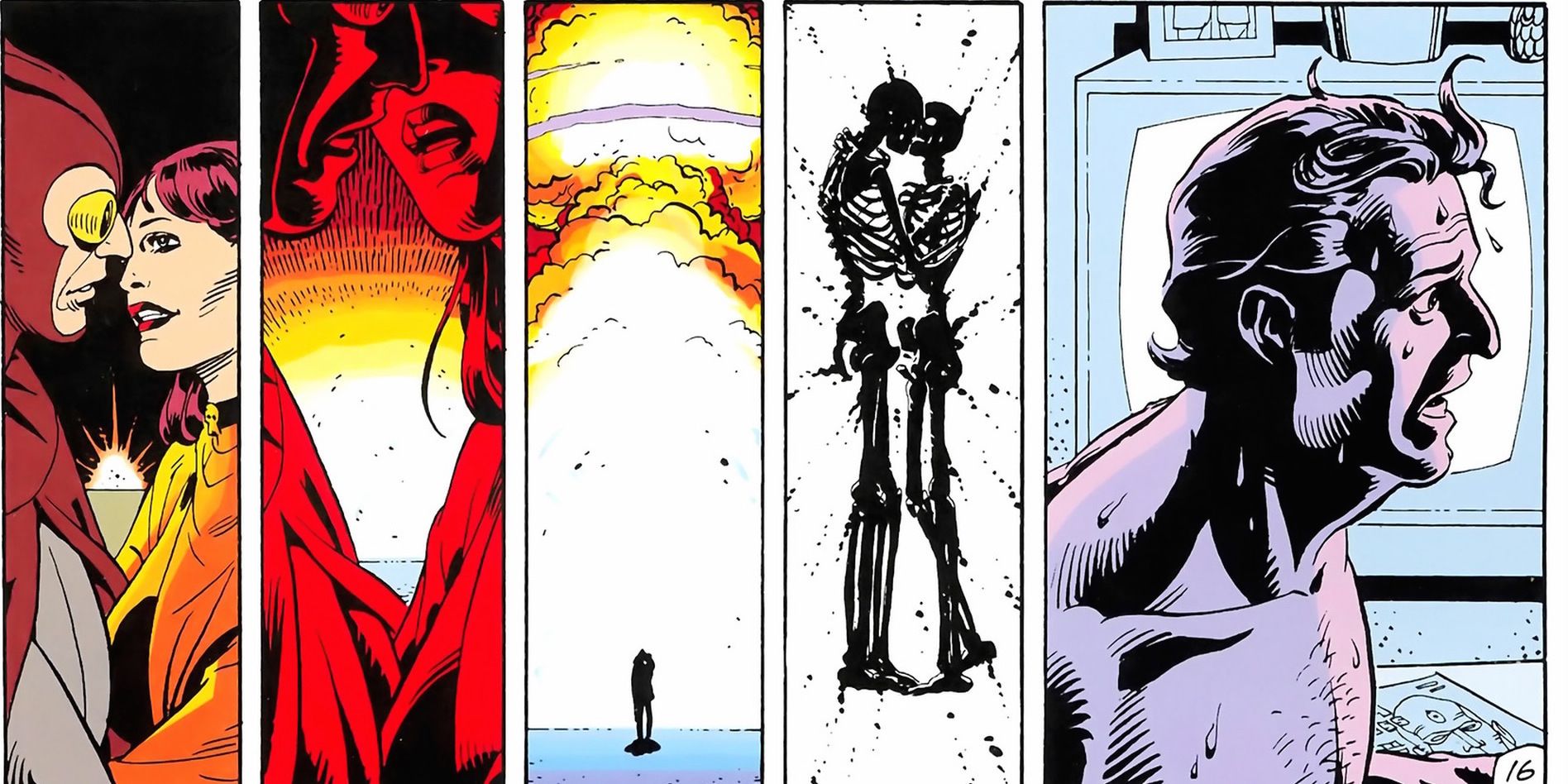

Inspired by Moore’s pioneering tale, artist Dave Gibbons defied the conventional comic art of the '80s, saying in an 2009 interview, "I wanted from the very beginning with Watchmen…every page of it, every panel, should very clearly be from Watchmen…the kind of comic books that were coming out at that time had kind of wild page layouts, like poster pages where there would be some big action shot…you'd always be very aware that somebody had drawn it...that was why I did the nine-panel grid.”

This nine-panel grid allowed for more exposition and detail than the average comic, (which it needed, given its dense narrative and use of symbolism). In addition, Gibbons employed a stiffer pen than he normally used to help carry out his unique aesthetic.

The highpoint of Gibbons' work is Fearful Symmetry, the fifth issue of the series. Gibbons uses symmetrical mirror image layouts throughout: page 1 is mirrored by page 28; page 2 syncs with page 27, etc. This eventually leads into pages 14-15 where each panel literally reflects its opposite image. It’s a towering achievement in graphic storytelling.

9. A Color Palette Like No Other

Colorist Jon Higgins' unusual palette for Watchmen was another way the series broke from comic tradition. Whereas most comic books use primary colors for heroes and secondary colors for villains, all of Watchmen was painted in secondary colors. This certainly reflected the ambiguity of the characters and their twisted morality.

Artist David Gibbons elaborated on why the color scheme for the series was so special: “John leaned very heavily toward, as you say, the secondary palette…it was the same range of colors you'd always been able to use in American comics, but it was colors that hadn't been widely used before. I think it added a lot to the atmosphere of the comic book…it reads less obviously as superheroes.” Higgins' work also helped to augment the fact that this was an alternate universe, makings things look aptly askew.

An example of Higgins' skill set is how he adjusted the colors in the issue The Abyss Gazes Also, which starts off with “Warm and cheerful” colors, before gradually darkening to match the issues bleak ending.

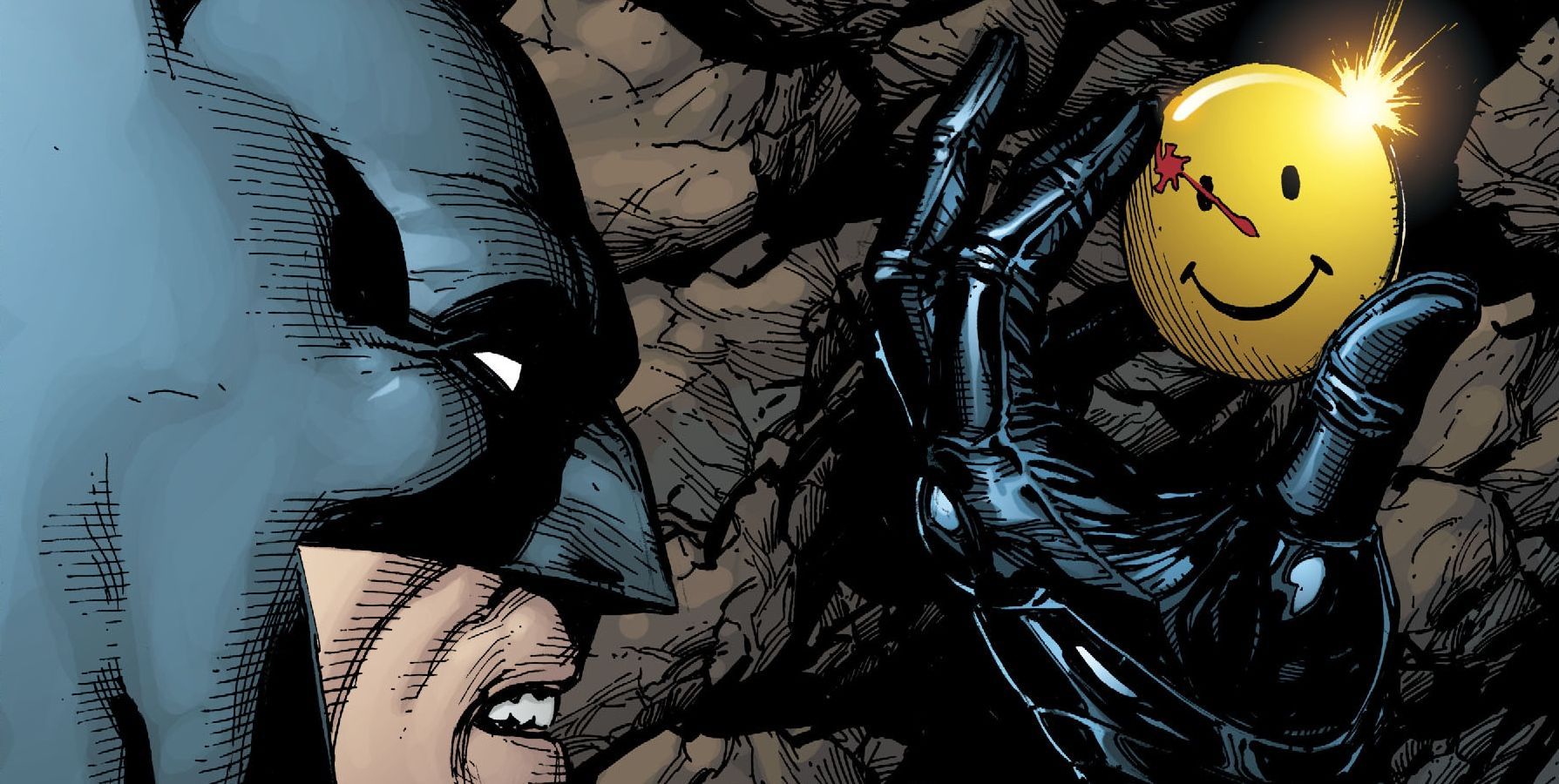

8. It’s a Watchmen World and We Just Live In it

Watchmen left a seismic imprint on the industry that went far beyond the '80s. While there were certainly many uninspired knockoffs, there were many genuinely great series indebted to its influence, including Warren Ellis’s The Authority and J. Michael Straczynski’s Supreme Power.

One can even make the argument that Moore and Gibbons' dark vision sparked DC to embrace more mature and sophisticated content like Neil Gaiman’s groundbreaking series The Sandman and the creation of their adult-oriented Vertigo line in the early '90s, with other series that peaked behind the four-color veil. DC continually dipped back in the deconstruction well with tales like 2004's Identity Crisis, and their 2012 Before Watchmen series, a prequel that was lambasted by Moore and other critics.

Even DC’s Rebirth, Geoff John’s new continuity-changing event, features characters from the Watchmen universe, injecting them straight into DCU continuity (for reasons yet to be fully explained). The series remains as indelible as ever.

7. The Incredibles

It may seem inherently odd that a family-friendly Pixar movie would gain inspiration from one of the bleakest adult-oriented comics ever produced, but even a cursory knowledge of Watchmen and The Incredibles shows notable similarities in narrative structure and themes between two superhero properties that couldn’t be more different in tone.

Stories about superheroes forced to retire? Check. A humiliated middle-aged hero who misses the good old days? Check. Lured out of retirement to stop a mysterious villain who’s hunting down other retired heroes? Check. A villain who thinks he’s actually the hero? Check. A master plan involving a city-destroying tentacled monster? Check. The only difference is that The Incredibles has a resolutely happy ending, while Watchmen does not (more on this in a bit).

Incredibles director Brad Bird claimed he was only passingly familiar with Watchmen before he made the smash hit film, but it seems impossible that his film would exist without it. Watchmen didn't just change comic books: it influenced comic book movies too.

6. An 'Unfilmable' Adaptation

Watchmen had been shopped as a potential film property as far back as 1986, when producers Lawrence Gordon and Joel Silver bought the film rights.

One of the first filmmakers interested in the project was Terry Gilliam, who deemed it “unfilmable” (the fact that Arnold Schwarzenegger was lobbying for the part of Dr. Manhattan probably didn’t help). Gilliam’s edict proved a curse: other notable directors including Paul Greengrass, David Hayter and Darren Aronofsky were all attached at various points, only to jump ship later on.

It took director Zack Snyder to finish the job of bringing Moore's vision to the big screen. And while the final product proved polarizing, there are still a host of impressive scenes in his 2009 adaptation (that opening title sequence still wows) and savvy casting decisions (Jackie Earl Haley was an inspired choice for Rorschach). If Snyder didn’t fully stick the landing, one could also lay the blame at Moore’s feet; the crotchety writer had been vehemently opposed to any film adaptation, saying Watchmen was designed to explore “the areas that comics succeed in where no other media is capable of operating," adding in a 2008 interview that the series used “a range of techniques” that didn’t lend itself to cinematic translation. No wonder it took over 23 years to make.

5. Story Expanding Supplements

Eschewing a letters page, the first eleven issues of Watchmen all ended with fictional supplementary material that helped fill the gaps on the early days of the Watchmen (and their Minutemen predecessors). Excerpts from the autobiography Under The Hood (by original Night Owl Hollis Mason), a dossier on the dangers of Dr. Manhattan, the psychiatric case file of Rorschach, newspaper clippings of the original Silk Spectre, and more all offered extra insight and back story -- which proved handy given the series' lack of a traditional superhero origin stories.

Moore also utilized quotes from iconic songs and poetry that echoed the narrative threads and character motivations. All of these additional elements helped fully authenticate the world Moore and Gibbons had conjured up. These extra layers make the story one you can return to over and over again. Or, in the words of Dr. Manhattan: “We gaze continually at the world and it grows dull in our perceptions. Yet seen from another's vantage point, as if new, it may still take the breath away.”

4. Who Watches The Watchmen...while watching The Watchmen?

One of the most adventurous and daring aspects of Watchmen’s plot was Moore’s use of parallel storylines. This device is used repeatedly throughout the series in a variety of motifs, such as one character’s inner monologue displaying over another character doing a similar action, or a contradictory reaction, creating a double meaning in the process.

The most prominent example of this stacking technique, is the literal use of a story within a story: The Black Freighter, a horror comic read by a youth at a newsstand in a New York City. This daring conceit would help expand upon the machinations of the characters within the “real” world of Moore’s story (more on this in a bit).

These elements, along with the aforementioned supplemental materials, make Watchmen impossible to fully absorb in one reading -- and that was by design. Moore had stated it might take "four or five times" to unravel all the knotted details, references and allusions that he and Gibbons had planted. In truth, you can read Watchmen hundreds of times and discover something new with each read. It's the gift that keeps on giving.

3. Tales Of The Black Freighter

A comic within a comic, Tales From The Black Freighter was one of the biggest (and oddest) narrative gambles of the storyline. So why did Moore and Gibbons include it in the first place?

The comic’s grisly storyline (entitled Marooned) tells the story of a doomed mariner, whose ship is destroyed by the dreaded pirate ship The Black Freighter. Riding on a makeshift raft -- which uses his dead crewman for flotation -- he sets off to his hometown to warn them of the evil pirate vessel. But he only succeeds in descending into madness.

In Moore’s master plan, Black Freighter goes beyond a mere garish distraction. It also mirrors the conflicted mental state of Adrian Veidt, who's willing to kill his associates (and innocent civilians) to achieve his goal of world piece, while at other times allowing allusions for other characters (including Dr. Manhattan and Rorschach). In addition, it serves another purpose: in a world where superheroes were both real and demonized, comic books would have to focus on something more outlandish to stay successful, and the Black Freighter comic certainly reflected that.

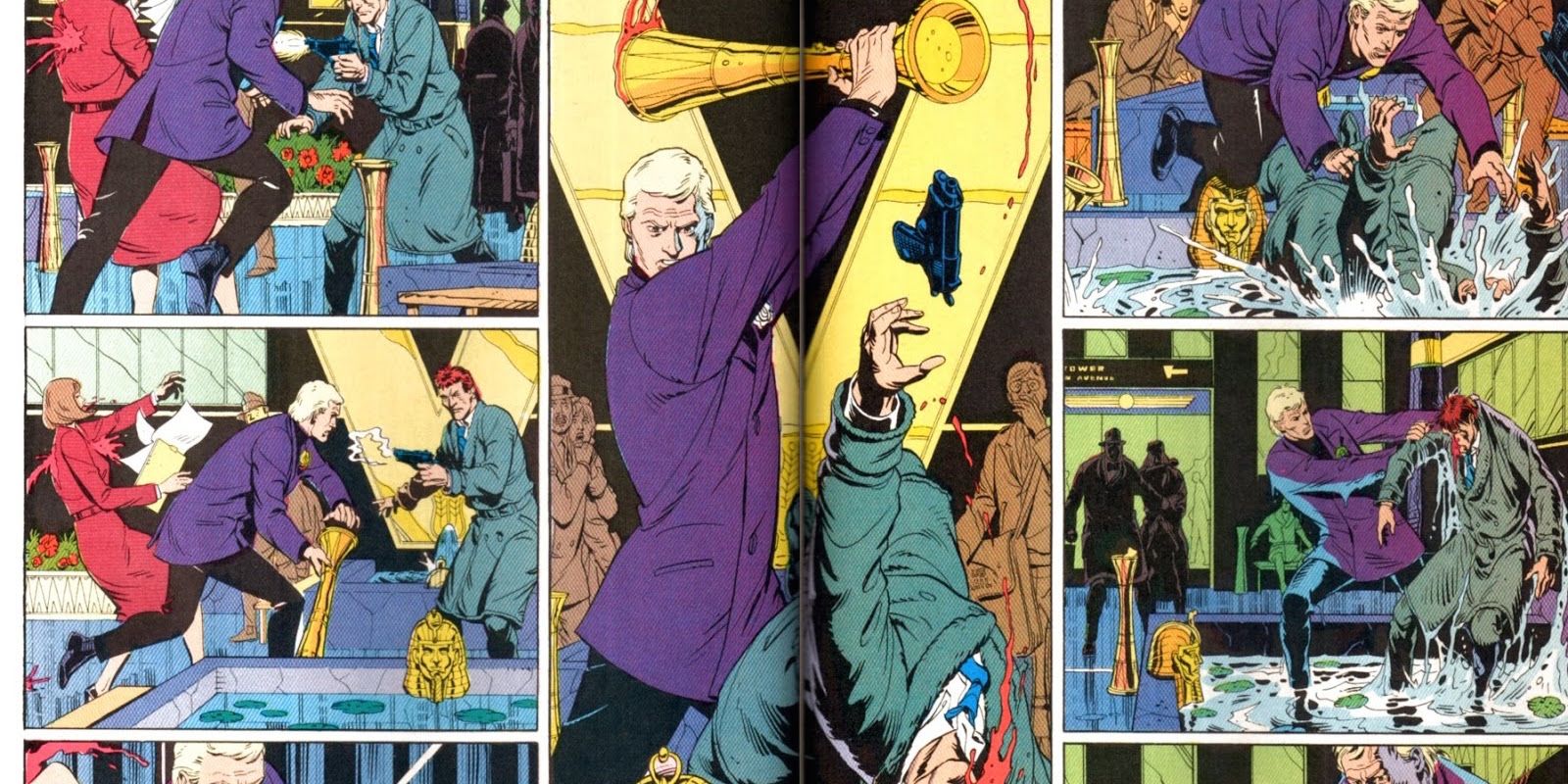

2. Controversial Ending

When it was revealed in the 10th issue (Two Riders Were Approaching) that Adrian Veidt (Ozymandias) was the villain in Watchmen, it promised an exciting standoff against his former teammates. But we should have known better than to expect a happy ending.

For a series about defying convention, the good guys winning the day wouldn’t mesh. But it didn’t make it any less devastating when Veidt revealed: “I'm not a Republic serial villain. Do you seriously think I'd explain my masterstroke if there remained the slightest chance of you affecting its outcome? I did it thirty-five minutes ago,” right before millions of New Yorker's died by the giant alien's explosion and resulting psychic shockwave.

Veidt’s notion that this catastrophe would create world peace polarized readers, as it lacked any comeuppance for the big bad of the story. Even Watchmen editor Len Wein found it problematic, primarily because it was derivative of The Outer Limits episode The Architects of Fear. He argued with Moore over the finale, which supposedly ended with Wein quitting the book.

Moore never truly lets Ozymandias off the hook however: the infamous final page leaves it open-ended if Rorschach’s tell-all journal will be shown to the world. But it’s that unresolved tension that has given Watchmen such longevity.

1.The Citizen Kane of Comics

Watchmen didn’t just take the world of comics by storm: its significance spilled far outside the industry and impressionable fanboys. It became a rarefied entity: a comic book treated with the same relevance as literature. This is one reason that the 12 issue series is often (mistakenly) referred to as a graphic novel (although the collected edition helped make its lofty status official). It's also why its been nicknamed the Citizen Kane of comics.

Watchmen is the only graphic novel listed on Time Magazine’s list of 100 Best Novels, it won a Hugo Award in 1988, and has received acclaim in a plethora of other publications not normally affiliated with superheroes. Its influence is so pronounced that its lettering style even inspired the design of the infamous comic sans font.

Watchmen transformed the medium, illustrating that comics weren’t just for children (yes, indie comics had already proven this, but not to the mainstream). And it's still inspiring passionate debates regarding its themes and significance three decades later. In the words of Dr. Manhattan “nothing ever ends,” including art itself.

---

Do you believe Watchmen has earned its place atop the comic book world? What did you think of the movie adaptation? Let us know in the comments.