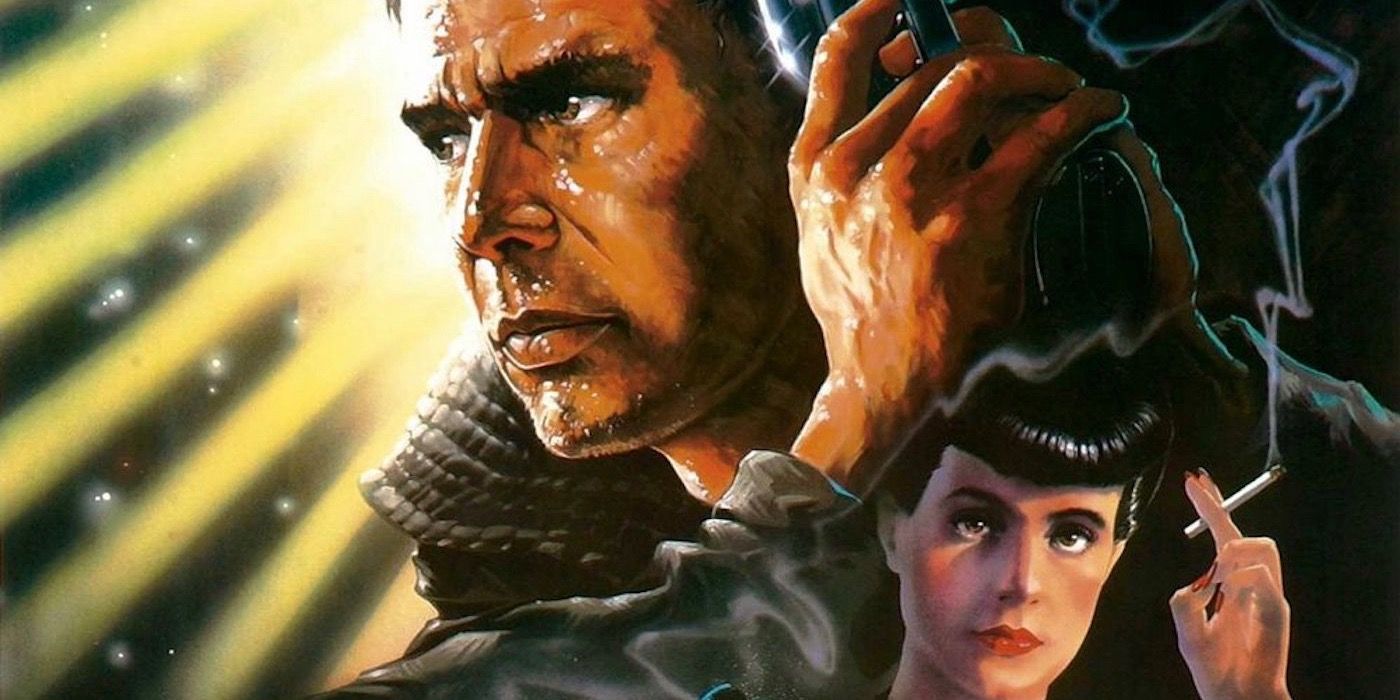

Is Blade Runner an untouchable sci-fi classic and one of the greatest movies ever made, or style over substance personified and, at best, wildly overrated? You're going to hear a lot of people claiming the latter in the coming weeks, but we're here to tell you that's not quite right.With Blade Runner 2049 impending, films fans of all creeds are revisiting Ridley Scott's tech-noir landmark in preparation for Denis Villeneuve's sequel (and to try and settle if Deckard really is a replicant). It is, after all, a sci-fi classic. And yet unlike fellow all-timers, the wider cultural sphere has an odd relationship with the loose Phillip K. Dick adaptation; whereas everybody loves Star Wars and the only bad word most have to say about 2001: A Space Odyssey is how overwhelming it is, this is the seminal movie that some people, frankly, don't like.It's not our place (or anyone's) to say you're wrong in liking/disliking a film but we would say that to dismiss Blade Runner as overrated misses so much of what makes it a societal touchstone as much as a cinematic one. Here's why you shouldn't call Blade Runner the "O-word".

Blade Runner Was Never Meant To Be A "Classic"

To really address being overrated, we first need to make clear how Blade Runner is rated in the first place. And, of course, it's very high. 90% on Rotten Tomatoes, 89 on Metacritic, strong ranking in the IMDb 250 and, perhaps most monolithically, #69 in the latest Sight & Sound Top 250, a poll of critics and filmmakers that is widely regarded as the closest we can get to an objective list of greatness. But it didn't start out this way.

Related: Rotten Tomatoes, Metacritic & IMDb Score Explained

The production of Blade Runner was an absolute nightmare, with methodical and fastidious director Ridley Scott clashing with the money men throughout filming (he was weeks behind after the first days) and, despite attempts to produce a more middle ground film (we'll come back to that), for a while it looked like all that blood, sweat, tears and t-shirts were for nothing. It got mixed reviews from critics and even less positive attention from audiences, making back $33M from a $28M budget (which was vastly inflated from the original $15M ballpark). Much of this is chalked up to the film hitting weeks after E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial and its frank dystopia clashing with the human optimism of Spielberg (something that likewise kneecapped John Carpenter's The Thing), although it's as much simply being too ahead of its time. The short of this, though, is that the film has an ignominious original theatrical release.

It was only when it arrived on VHS that reputation started to the shift and, over the 1980s, people began to see Scott's vision for what it was. Re-screenings became regular events in LA and at conventions, slowly building up its myth. Eventually, the director was able to give a more refined take with the 1992 Director's Cut (albeit done via notes while he finished Thelma and Louise), and from there the movie only grew in prestige. It became a classic over a period of decades, building slowly but surely.

Blade Runner Was Underrated

Now, cult classics aren't uncommon - indeed, it would be a disaster if a movie's initial reaction had to be its enduring legacy - especially in this early home video era (indeed, fellow E.T. victim The Thing thrived in a similar way), and the cultural segue into the internet sees many gaining unexpectedly large footprints, but Blade Runner's something different. It's grander, as a movie and where it went. It's the cult classic, the best example of a movie that went from underground hit to mainstream all-timer.

Plainly, it was originally underrated - and, even after reevaluation, it's not what a film of its stature traditionally is. Understanding this isn't essential to appreciating the movie itself, but is in grasping its reputation. By the nature of the development, there's a cultural cap on it; whereas the New Hollywood films of a decade before have an immense respect across all sectors, Blade Runner skewed into a specific generation. It's reductive to go so broad, but its status as a sci-fi classic came from a different voice to those heralding the likes of Close Encounters or Star Wars. Regarded as something more universal than it is can only lead to misunderstanding.

The Various Versions Really Don't Matter

A big part of the Blade Runner narrative from flop to undisputed classic comes from the sheer number of versions that exist, allegedly showcasing the nuanced genius. In total there are seven variants: the Workprint prototype version (originally the closest to Scott's vision); the San Diego Sneak Preview version (the theatrical version with three extra scenes); the Theatrical cut that struggled with audiences; the International cut (the theatrical version with three more violent, extended scenes); the US broadcast version (the theatrical version with toned down violence); the Director's Cut (Ridley Scott's first revised attempt from 1992); and the Final Cut (the latest version from 2007).

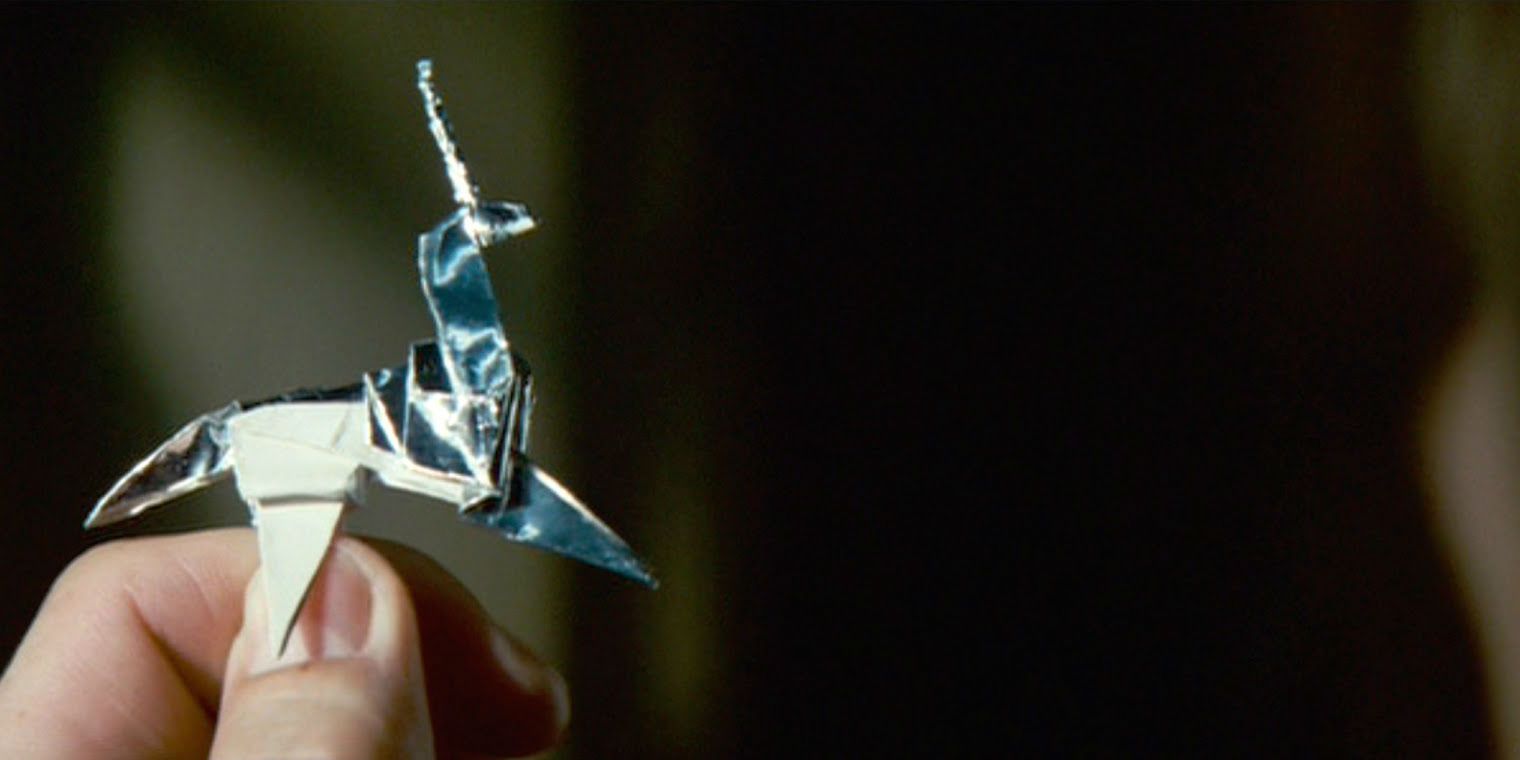

However, in practice only three really matter - the Theatrical (TC), Director's (DC) and Final Cut (FC), with most of the others evidently variants on the former. There's a lot of minor differences and slight effects alterations between them, but on a macro sense they hinge on a few specific moments: the TC features a narration delivered with sardonic disinterest from Ford that undercuts key emotional moments and a happy ending where Deckard and Rachael run off into the sunset; the DC removed both of these and added in a couple of moments that teased the possibility of the hero being a replicant, most pointedly a unicorn dream that ties into the final origami piece; and the FC is a technological refinement with corrected images in some shots, superior visual and audio quality, as well as additional footage that smooths the Deckard identity mystery. The latter is the undisputed best on a narrative, thematic and technical level, preferred by Scott, Ford and Blade Runner 2049's Denis Villeneuve.

Related: Which Is The Best Version of Blade Runner?

But, as you may have got from those "differences", it's all subtleties. Villeneuve says that while 2049 follows on from the FC, his favorite remains the TC he grew up with, and when you get down to it, all the seven versions of Blade Runner are intrinsically the same movie. The narration and happy ending certainly provide a barrier to the climax of the TC - it overexplains the theme and sands the whole story down to a simple love story - but the alterations aren't as seismic as the legend suggests. At their core, they all tell the same story and ask similar questions of humanity.

Indeed, Blade Runner's changes are definitely nowhere near as brutish as what George Lucas did to Star Wars. In fact, counting all re-releases, the original 1977 movie has more alternate takes than Blade Runner. The distinction is how it's presented; in popular parlance, the big changes came with the 1997 Special Edition, even though subtle adjustments (including the Episode IV: A New Hope subtitle and select lines of dialogue) had been made prior, some as early as 1981, and there were two equally seismic updates in 2004 and 2011. The only reason such a distinct fuss is made about each take with Scott's film - to the point a TV edit enters the discussion - is because Warner Bros. outwardly embraced the different versions that exist whereas Lucasfilm suppresses them.

The whole multiple version fallacy is more a fallout of production ills turned into a marketing tactic to highlight the film's lofty status than it is a sign of true creative importance. What does this have to say about the film's reputation? Well, ostensibly all they really do is create a barrier to getting into it and a needless defense to enjoyment; those new to film often spend far too long prevaricating over which version they should watch or chalk up finding the movie so-so to having viewed the wrong one. But, on a bigger scale, it just distracts from the art itself. There's variation, but not enough to warrant such a dominant portion of the discussion - which is really kind of fitting.

Blade Runner Isn't What Its Reputation Suggests

All of that history is important because it shows how Blade Runner has been reframed as something that it really isn't. We're talking about a movie striking for its sublime, ageless visuals that spends the majority of its time in a muted, grungy near-future where characters are non-plussed by their surroundings. It's in the sci-fi genre and yet for all of Ridley Scott's incomparable world-building, the story he's telling is more of a noir, all smoky rooms and grizzled detectives. But a noir so about feel and emotion over narrative that it came across as cheaper with the genre-typical narration. That's a lot of ingrained, ambitiously balanced contradictions for something that by its import demands to be viewed.

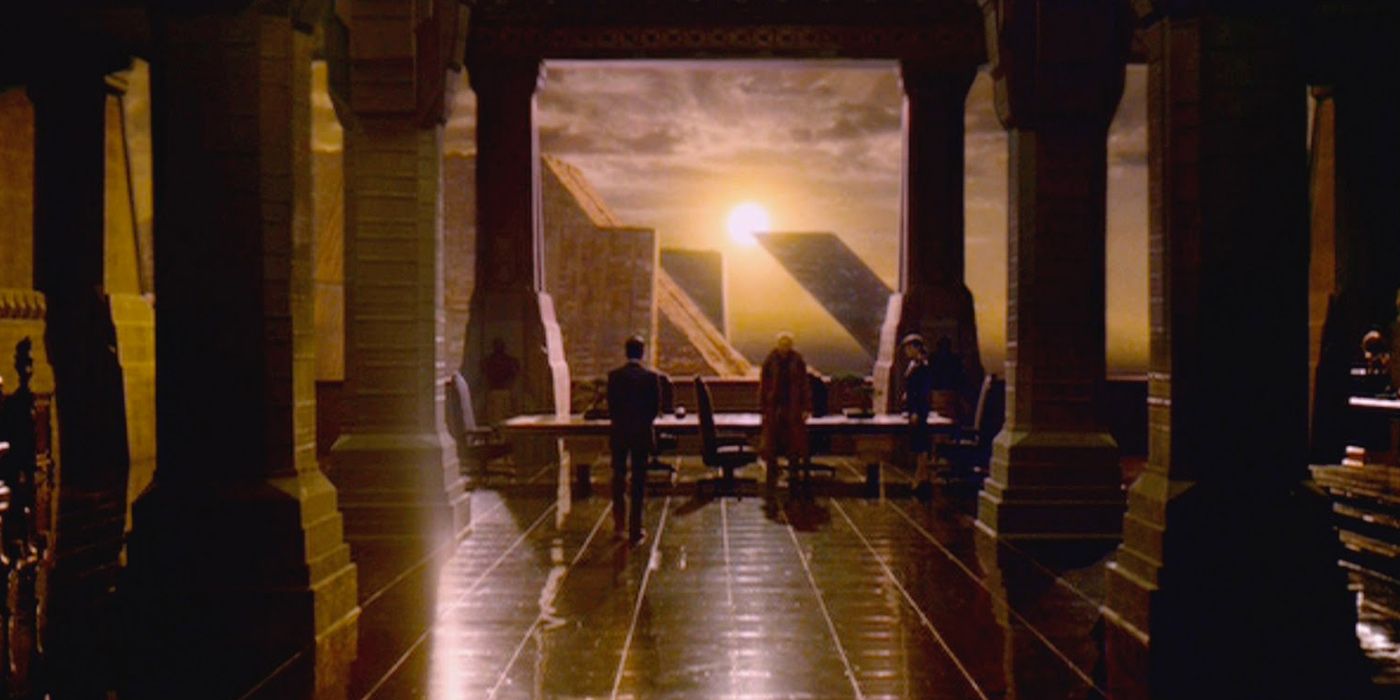

What really is Blade Runner, then? That it's a technical marvel is well documented in its associated criticism, the craft inherent with production (behind-the-scenes documentary Dangerous Days is three-and-a-half hours of jaw-dropping filmmaking process) and its far-reaching influence across visual mediums. Its soundtrack from Vangelis may be the finest score to a film ever, even giving the work of John Williams a run for its money. And there's an inherent poetry to so much of it, not least the paradoxically broken yet lyrical "tears in rain" soliloquy (Roy Batty's final words are totally unmanufactured, on a fundamental level not following styles like the rule of three, yet evoke so much emotion thanks to the real life it teases). Cinematically, Blade Runner offers so much.

None of this means there isn't a story. Narratively we're dealing with a former cop hunting down rogue replicants - outlawed in the far-off future of 2019 - who have only come to Earth in a bid to get more life from their creator. But story-wise, we see the breakdown of Harrison Ford's Deckard, reluctantly pulled into the fight again only to slowly be broken down by the fine line between "retiring" skin-jobs and murder, emblemized by his feelings for one-of-kind replicant Rachael. As it wears on, the distinct possibility he himself isn't actually human becomes increasingly prevalent which, contrasted with Roy Batty's slow acceptance of his mortality, breaks down the definition of what it is to be human.

Batty is perhaps where the film's true nature comes to light. He's the antagonist insofar as he's who our protagonist is hunting and is framed as dangerous, yet his motivation - he wants more life, father/f*cker - is so fundamentally relatable, his degradation understandable. At the end of a brutal fight with Deckard, he even saves his nemesis purely out of acceptance of their shared existence. You can watch Blade Runner as his story - just as you can watch Scott's Alien prequels as David's - and find a fully rounded "hero", one with more innate righteousness in him than the conventional lead. And that's not an accident.

This is why the oft-cited "rape scene" fits; it's an essential part of Deckard's spiral, showing his conflicting love and lack of respect for artificial humans. Yes, it's definitely uncomfortable viewed in 2017 and would not have made it into the movie had it been released today (or would certainly have been presented differently,) but it highlights that conflict and makes his eventual decision to run away with Rachael - one the film makes clear is out of genuine emotion - actual evolution.

-

All of this is a mixture of craft and storytelling that locks to create a fiery, eye-opening experience of our true future, symbolically if not literally (we're just over two years out from the movie's setting). The meditative thematic aspects are right there in the emotions of the story, as towering as the Tyrell corporation building.

Blade Runner is inherently different. That's what made it so troubled a production and led to it taking so long to become regarded for what it truly was. That's what gives such weight to subtle changes in stark contrast a popularization of director's cuts. And it's what makes it such a unique story still. Blade Runner is not a film that ever could be universally beloved, but that's not an excuse to say it's overrated.