As far as the movie business is concerned, the most widely-quoted line ever to come from a screenwriter was one that never appeared in a screenplay; namely, the legendary William Goldman's famous adage about the average industry insider's grasp of box office prospects: "Nobody knows anything." Granted, Goldman was saying this in an era before computer modelling of audience demographics, to say nothing of the entertainment press of the day not reporting on ticket sales like sporting events.

All the same, this has remained somewhat (frustratingly) true. However much of a science Hollywood has gotten its release schedules down to (and how few and far apart genuine surprises have become) unplanned megahits and surprise shortfalls still happen. And when they do, everyone who didn't "know anything" wants to at least be the person who figured out a lesson for next time - even when there isn't one. Such is the case now with Steven Spielberg's The BFG.

The BFG was never expected to run away with the box office, with few analysts projecting that the film would be able to match the box office draw of, say, Finding Dory. Nevertheless, the film's slight performance with U.S. audiences was newsworthy given the combined players involved: Steven Spielberg teaming up with Disney for a family blockbuster based on a beloved Roald Dahl book for kids is the sort of thing that most everyone seems to agree should have opened better, or at least with better legs.

Then again, there isn't a lot of data to suggest that Roald Dahl adaptations are a guarantee of box office success. Dahl certainly wrote a great number of beloved, long-enduring children's novels; but outside of the big grosses that greeted Tim Burton's Charlie & The Chocolate Factory in 2005, most Dahl adaptations (James and the Giant Peach, The Witches, Matilda) were bigger on home video than they were in theaters. The best known prior version of The BFG, an animated made-for-TV film, has a nostalgic following in the UK but only sporadic worldwide. And while Disney's animated features and branded franchises (Marvel, Star Wars, Pixar) are generally always moneymakers, the studio's live-action fare can be more of a toss-up.

But, for whatever reason, The BFG has come to be judged by some as a referendum on the enduring box office appeal of Steven Spielberg. In some respects, it makes sense: He's spent a career becoming, intentionally or not, synonymous with the concept of blockbuster entertainment. For a time, "Spielbergian" was Hollywood's favorite way of describing big crowd-pleasing hits; and while not all of his films have been successes, those that have practically defined the very idea of success throughout the '80s and '90s. Now an elder statesman of the medium, he's transitioned largely to focusing on drama (usually related to historical events) with only the occasional dip back into the blockbuster pool; still, when Spielberg does jump back in, he's generally expected to make a big splash. So when it doesn't happen, as is the case with The BFG, people start asking questions.

For the entertainment press, the narrative is too tempting to ignore: Spielberg didn't just become king of the blockbusters, he did so with a focus on making whimsical, heartfelt features infused with nostalgia and childlike wonderment (which quickly cast him in the pop-culture persona of a Peter Pan figure) - and the narrative of such a person losing a (literal) "magic touch" has an element of intrigue that the otherwise non-story of a career speed-bump doesn't. People love to see a hero fall, and for Hollywood entertainment writers "Steven Spielberg isn't so bulletproof after all!" is one of the most attractive possible versions of that.

But is it fair to be wheeling such talk out with such fervor now, for this project, in this (so far) bumpy summer movie season?

As laid out above, The BFG could hardly have been expected to be an E.T.-level smash - not sandwiched between Finding Dory and The Secret Life of Pets in an emerging box office paradigm where there's evidently only room for one mass-market family film at a time. Plus, while it certainly recalls the bygone era of deliberately paced fairytale-style kids movies that were prominent in the era when the book was written, it's a far cry (for good or ill) from the kind of kinetic, fast-moving storytelling that defines family entertainment in 2016. Indeed, it's hard to imagine The BFG gaining much traction without Spielberg's name and Disney's brand attached to it to begin with.

But the fact of the matter is, despite the association of his name with childhood entertainment, Spielberg has made relatively few films that would explicitly qualify as childrens' entertainment (and when he has, the results have been decidedly mixed). That he's thought of in this way (or, rather, was for the bulk of the first half of his career) is largely the result of his being the breakout superstar director/producer of the post-Star Wars blockbuster era that also happened to be the beginning of big-ticket movies and moviegoing by children and teenagers becoming joined at the hip.

Very few of the "nostalgic classics" of Spielberg's early hot-streak (read: the decade-and-change between Jaws in 1975 and Indiana Jones & The Last Crusade in 1989) were aimed even primarily at a younger audience, and those that can somewhat seem to be tend to be the projects he produced rather than directing himself. That youngsters were captivated by the likes of Raiders of The Lost Ark, Gremlins or Back to The Future was more the result of Spielberg and collaborators like Joe Dante and Robert Zemeckis chasing their own nostalgia than trying to speak to the youth of the '80s directly. Still, the overall effect was still the same: a mass-shift in blockbuster cultural away from adolescence and onto childhood as an emotional center, and with it a tautology that afflicts the thinking of a generation of film writers: "Steven Spielberg movies defined my childhood, therefore Steven Spielberg is defined as a children's filmmaker."

In fairness, Spielberg leaned into the role. Even as his own directorial focus shifted to more unmistakably adult fare like Schindler's List and Saving Private Ryan (notably, both following the critical and box office failure of one of his few outright kid-targeted features, Hook), the "Spielberg Brand" stayed comfortably affixed to family appeal. Yes, even his "crowd-pleasers" got more cynical in the '90s and early-2000s (Jurassic Park, A.I. and Minority Report are cautionary sci-fi rather than "awe" sci-fi), but his producer title - and unmistakable fingerprints - ubiquitously adorned the likes of Casper, The Flintstones and Balto in theaters while he "Presented" Millennial kiddie-TV staples from Tiny Toons to Animaniacs to Freakazoid. And then there was Deamworks Pictures, where as the "S" in "SKG" he was further attached to the first run of animated films in decades to seriously challenge the Disney behemoth.

In other words: Yes, it's not entirely accurate to view Steven Spielberg as a childrens' filmmaker, but his reputation as a filmmaker with fairly strong instincts about what children are seeking out in entertainment is more than well-earned. So where did those instincts go as relates to The BFG?

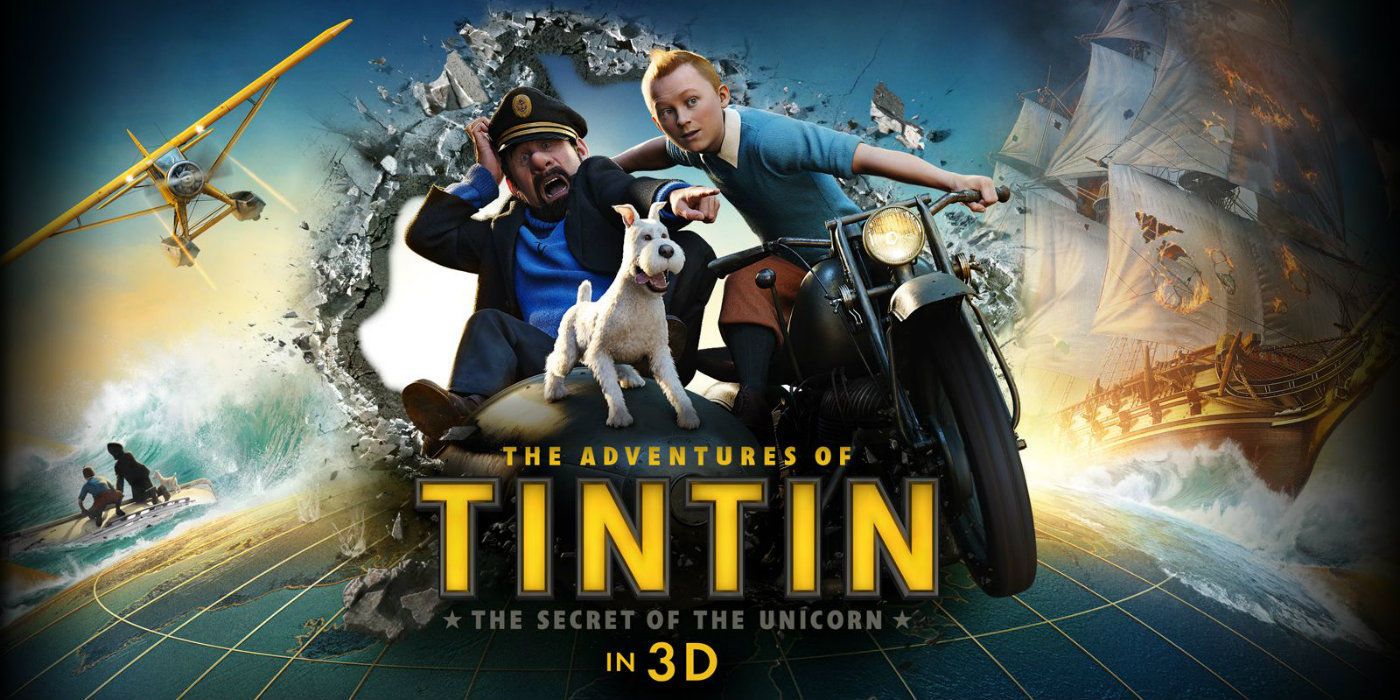

It would make sense to chalk it up to the niche-ness of the BFG property, or to point to the fact that it's actually been a long time (in Hollywood math) since Spielberg actually had a giant-scale blockbuster hit as a director (as a producer it's another story, thanks to the Transformers movies and Jurassic World). In fact, his last "Spielberg-sized" box office smash was the not-so-beloved Indiana Jones & The Kingdom of The Crystal Skull in 2008. Since then , his directorial efforts (as befits a filmmaker with nothing to "prove" as a ticket-seller) have largely been prestige projects like Lincoln, Munich and Bridge of Spies; and the lone "family blockbuster" in the mix - the animated Peter Jackson collaboration The Adventures of Tintin - was a success (especially in Europe, where Tintin is better known) but not of the runaway type. In some ways this is called being a victim of one's own success: turn enough lead into gold and people start expecting it even when you're just trying to make a (very nice) paperweight.

It's also entirely possible (and perhaps more reasonable) to consider that filmmakers (even once-in-a-lifetime visionaries like Steven Spielberg) are human and humans' interests and attendant engagement with other humans tends to change over time. As laid out above, Spielberg's generation of pop-art auteurs largely "backed into" their connection with Generation X and Millennial children while re-exploring their own memories. That the children of the post-Internet generation are "different" from their predecessors (as the kids who grew up on Spielberg movies were from theirs) has been widely remarked upon.

Simply put: It can't necessarily be called a surprise if director whose connection to a prior generation's young audience was never "cultivated" (because it came naturally) in the first place no longer appears to have a window into the current young audience's mind. In this respect, the choice of post-2000s kid-appeal material speaks volumes: Mega-budget tentpoles based on Tintin and The BFG are very much the decisions of a Boomer parent working from a "what me and my kids would both enjoy" mindset; and that's before you recall that this particular Boomer parent passed on directing the first Harry Potter installment and regards the now nearly two-decade ascendant popularity of the superhero genre as something of a fad.

So does that mean Spielberg really has "lost" some key component of his box office appeal? Doubtful. True, his onetime place as Hollywood's chief seer of what the under-12 set is going to go nuts for seems to have been supplanted by "new" industry figures like Pixar's John Lasseter and Marvel's Kevin Feige; but his actual box office acumen overall remains almost startlingly strong. Say what you will about the quality of the results, but it was Spielberg who helped push for Paramount to go all-in on live-action Transformers movies and who personally lobbied to woo Michael Bay onto the franchise even though the younger director - who'd once worked transporting storyboards for Raiders of The Lost Ark - was at first emphatic about not doing a "stupid, silly toy movie." (Spielberg's pitch to Bay: It's not a "toy movie," it's a movie about a boy who buys his first car to impress a girl.)

The next few years should prove especially interesting for Spielberg in this area, as he's set to dip back into full-on blockbuster territory for the first time since Crystal Skull with the feature adaptation of Ready Player One - a sci-fi adventure set in a virtual world create out of 1980s pop-culture ephemera (more than a little of which came straight from Spielberg himself) - followed by Indiana Jones 5. Whether that counts as coming full circle, embracing or even commenting on his own lasting impact remains to be seen; but the idea that the era of Steven Spielberg has passed because of the so-so reception of one Disney movie? That's a tale so unlikely not even Steven Spielberg could sell it.

The BFG is now playing in theaters around the globe.