In the case of crime dramas, what hooks us in first? Could it be the personalities of those we watch solve these cases? Not all of them are the dry, studious types who can’t inject a little flair into the proceedings – though one must always be certain the job is a success. Or could it be the nature of the investigations themselves? Each one is bound to have a few twists and turns, especially for the purposes of popular narratives. We get wrapped up in every new lead, red herring, and possibly new victims, and hopefully it all leads to a satisfying conclusion.

From the smoky film noir parlor rooms of the 1940s to the murder mysteries both factual and fictional, plenty of detective stories have left their mark on cinema. Whether it’s a charismatic lead, a winding narrative, or both, these 20 features are only a small fraction of this great genre, though they represent the best of the best. Here's Screen Rant's take on the 20 Best Detective Movies Of All Time.

20. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011)

Few detective stories are as brutally aberrant as Stieg Larsson’s “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” and for that reason, perhaps it was more than appropriate that David Fincher helm the English adaptation. The material provided to Fincher is bleak, which he certainly isn’t a stranger of, and the vision he’s provided in past efforts (which we'll get to shortly) appropriately matches the tone of the novel and its setting.

Of course, it’s rather easy to note Rooney Mara’s stunningly committed portrayal of investigator Lisbeth Salander, and she shines through Fincher’s typically dreary atmosphere. But, perhaps what stands out the most is Fincher’s brisk pacing. His film may be a little over two and a half hours long, but the direction of most detective fiction, it would seem, is more assured and academically conducted. In this case, Fincher deftly guides his audience through the story’s twisty narrative fast enough to keep them entertained, and yet still showing restraint when concerning key details.

19. Dirty Harry (1971)

If you think about it, there aren’t many discernible qualities that separate Clint Eastwood’s Harry Callahan from his ‘Man with No Name’ in Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy; just trade in the Western garb and a regular six-shooter for suits and a .44 Magnum that could blow your head clean off. Even in the final shootout with Scorpio, the dilapidated structures and the desert mountains bear a striking resemblance to any of the locales Eastwood would have been familiar with in the mid-‘60s.

Nonetheless, Eastwood’s Dirty Harry is the consummate stoic tough guy; it’s a routine, but nothing’s for show and his unorthodox methods are genuine. Eastwood plays him simply, and his behavior and mannerisms are simple, and yet the character remains strikingly enigmatic. It shouldn’t be any wonder the film turned into a franchise, spawning four sequels spanning the better part of two decades. The only unfortunate aspect of the film’s history has been an epidemic of misquoting lines.

18. The Thin Man (1934)

In a list mixed with archetypal and unconventional personalities, these two detectives Charles, Nick (William Powell) and Nora (Myrna Loy), find themselves straddling the line between both. On the one hand, they both, especially Nick, exemplify how a charismatic Hollywood actor is to present himself or herself. Like many an actor in his era, Powell’s Charles is calm, cool, collected and carrying a silent authority that can be brought to high volume – getting physical – when necessary. On the other hand, these two are humorous and witty enough to betray those conventions and stand on their own. Also, they’re casual drunkards, but because it was Hays Code Hollywood, it looks classy.

The defining moment for any murder mystery is the big reveal, and the climactic dinner party scene in The Thin Man features a tense, slow build to the unveiling of the real killer’s identity. The suspects crowd the table, and the camera moves back and forth between each of them and Nick as he concisely runs through the events implicating all of them. Anyone could be the true killer, and when that reveal is made, it is most satisfying.

17. Insomnia (2002)

Christopher Nola has made himself a reputation for his unique vision, especially with regards to his projects outside of his Dark Knight trilogy. For that reason, he joins David Fincher as a director with multiple films on this list, and it starts with the film that got him Batman Begins: Insomnia.

Many films on this list stand apart in one way or another, but Insomnia is particularly unique in one fashion. As we will see, it doesn’t separate itself from the rest merely due to its psychological nature – even if most other films here cannot boast such qualities – but rather for the moral ambiguity of its protagonist. Considering some of the other detectives included here, Detective Will Dormer (Al Pacino) is no saint, even if his character does find redemption in the final acts. Even still, we desperately wish for him to find his way back to the right side of the law thanks to a strong performance from Robin Williams as Walter Finch, the chief antagonist.

16. Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

Roger Rabbit is potentially one of the last fictional talking mammals anyone would expect to intentionally commit a crime, and yet he found himself at the center of a story of “greed, sex and murder,” as Eddie Valiant (Bob Hoskins) puts it. With Who Framed Roger Rabbit, director Robert Zemekis and company created an innovative amalgamation of live-action and animation that gave viewers a tangible world for their favorite characters, including Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny. To be fair, however, the film is far more intelligent than one about an animated character framed for murder has any right to be.

More important than any sleuthing is the character arc involving Valiant. Hoskins gives an admirably game performance considering most of his dialogue is being spoken at something that isn’t there, and as a result, the subplot of avenging his brother’s murder at the hands of a sadistic toon is that much more affecting. With that said, what’s equally commendable is the film’s commitment to dark, even disturbing moments to express maturity, given its intent as a family film.

15. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005)

Most recently, Shane Black used Hollywood’s peculiar history in the seventies as part of the narrative in The Nice Guys, but with Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, he completely lampoons conventional filmmaking and film industry culture -- while providing a decent mystery along the way. Much of the focus here is on the comedy, as Harry (Robert Downey, Jr.) and Perry (Val Kilmer) play off of one another with a screwball zany-ness that makes them a charming odd couple.

While certain aesthetics and subject matter can’t escape from Black’s satirical pen, his love letter take on film noir comes across as pastiche rather than parody, and his affection radiates with genuine panache. The sometimes cold, steely blue visuals are an interesting, eye-catching take on what one might interpret as a cynical atmosphere in film noir, so in that way, the conventions are modernized. Overall, if you enjoyed The Nice Guys, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang will be well worth your time.

14. Zodiac (2007)

The identity of the Zodiac killer is one of America’s greatest, most haunting mysteries, quite like the identity of Jack the Ripper for England. Though much like the latter’s film From Hell, David Fincher’s Zodiac seems to have its own ideas about who the culprit was, even if the case is never fully resolved. Speculation aside, Fincher can help spin a good yarn, and thanks to James Vanderbilt’s screenplay based on Robert Graysmith’s book of the same name, Zodiac is yet another film of his on this list.

The tension in the film is often understated, especially when the Zodiac killer isn’t trying to make his presence known. But when his is seen and heard onscreen, the suspense ratchets up to an unbearable degree. As if you couldn’t more immersed into this whirlwind, the production design is stellar and the visuals contain a slightly de-saturated quality that enhances the feel of the time.

13. Brick (2005)

Rian Johnson’s indie starlet Brick is one of those movies that feel like a dream. It isn’t dream-like in a visual sense, but rather through the dialogue, characterization and events that take place. For those who imagine themselves as a Humphrey Bogart detective-type, it’s how Brendan Frye (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) carries himself in what can only be described as Johnson’s fantastical worldview in the confines of neo-noir convention. It’s a love letter that has every bit the volatility of any of the classics.

Mostly though, it’s all thanks to Gordon-Levitt’s calm, assured performance as an unlikely hero. What he lacks in control over matters he makes up with confidence and persistence. During scenes such as his first interaction with Dode (Noah Segan) or even meetings with Assistant Vice Principal Trueman (Richard Roundtree), he immediately grabs your attention with measured conviction. Then, there are moments such as Dode’s execution and Brendan’s sickened reaction to it, and though it seems reality has entered the fold, he still comes out of the other side the same fantasy.

12. L.A. Confidential (1997)

Film noir doesn’t need the lowly lit, smoky atmosphere alluded to earlier or calmly cool detectives getting amongst the seedy underbelly of society. As L.A. Confidential reminded us nearly two decades ago, the brutality can be unchecked and the violence can have an exuberant punch. Additionally, with a genre that has given us hard-boiled private eyes like Jack Nicholson in Chinatown or any of Humphrey Bogart’s similar personas throughout the ‘40s, it’s refreshing to see a compelling tag team in the form of Guy Pearce and Russell Crowe, both of whom were relatively unknown at the time of release.

Like many a great detective story, the plot is complex and full of side narratives and colorful characters, and though L.A. Confidential’s material is quite wieldy, it remains hypnotic in its depiction of police corruption. Audiences nowadays might even find its depictions of systemic racism and general prejudice in the justice system to be accurately reflective of today’s current issues.

11. The Third Man (1949)

One high praise many have given Carol Reed’s The Third Man is its atmospheric cinematography, and how could it not be against the glorious backdrop of Vienna? Post-war Vienna seems a timely setting for the glass half empty mentality filling all film noir. The scope is ambitious and as grand as the locale, but Reed’s film isn’t always atmospheric in the traditional sense of film noir. Cinematographer Robert Krasker makes frequent use of dramatic and canted angles to provide a feeling of uneasiness akin to something more standard from the genre.

In addition to some standout performances from a majority of the primary cast, including Joseph Cotton, Orson Welles and Alida Valli, Anton Karas’s score is certainly something peculiar. At first listen, his rumbling acoustic guitar seems to mismatch the moments of tension it means to accentuate, but it effectively aids the film’s overwhelming tone by raising those questions within the viewer.

10. Chinatown (1974)

It seems more modernized interpretations of film noir – in this case, anything from the New Hollywood era to the present – became more unpleasant as time passed and the limitations of what could and couldn’t been shown on film lightened. Chinatown may not be as brutally violent as those that would follow, but it didn’t need to be. Most everything about the film screams unpleasantness, which is certainly a far cry from just cynical.

A fair portion of it comes from Jack Nicholson’s portrayal of private detective Jake Gittes, who comes across as exhibiting the cold calculation of Guy Pearce’s Ed Exley in L.A. Confidential and a dialed back version of Russell Crowe’s mean streak from his Bud White in the same film. But most of the nastiness is attributed to the subject matter of incest, something the Hays Code era of Hollywood would’ve had a bit of difficulty discussing – most wouldn’t have dared touch the ending director Roman Polanski was able to accomplish here.

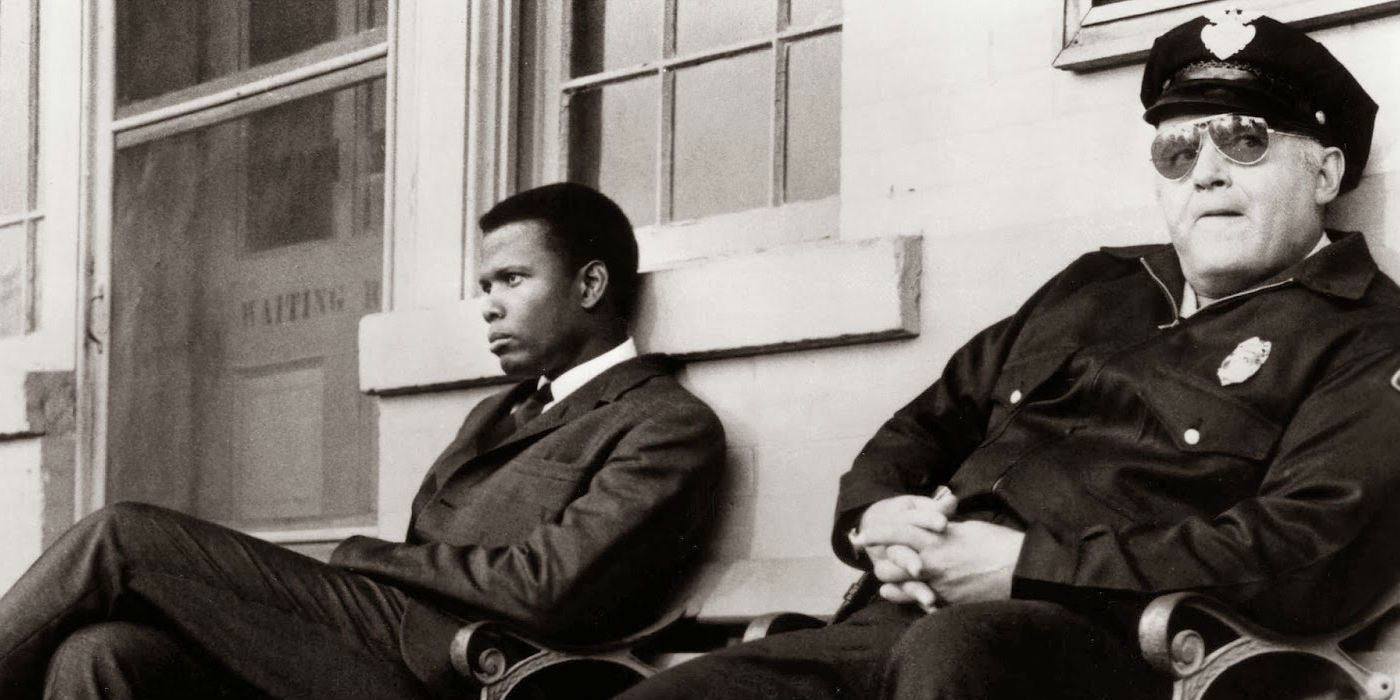

9. In the Heat of the Night (1967)

Not many movies, or the people behind them, could have been as brave as In the Heat of the Night. John Ball’s novel of the same name was already incredibly timely, published in the thick of the civil rights movement, and being released only two years afterward, the film version was equally so, as well. As a result, the film is one of the most important to come out of the ‘60s, an era when Hollywood was brushing off its archaic moral structure.

Whether it was In the Heat of the Night or Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Sidney Poitier always found himself in the center of these discussions, and for good reason. His power and charisma as Police Detective Virgil Tibbs is enthralling, especially when confronting, verbally and physically, to the surprise of many, the racism of white America – which, to be fair, is a decent majority of this picture.

8. Blade Runner (1982)

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner has simultaneously bewildered and fascinated viewers for a few decades now, and it’s slightly understandable that the initial reaction to it wasn’t as positive as it is today. The passage of time brings about newer perspectives, and as a result, new lights were shone upon the film’s existential and philosophical themes and its distinguishing flavor of neo-noir.

Like many of the films seen here or elsewhere in the genre, Blade Runner wears its cynicism on its sleeve, and its low-key lighting heightens that tone. The lighting here is curious, though, as it serves more than one purpose. Ridley’s vision of the future fits the post-apocalyptic science fiction bill perfectly, and the heavy use of chiaroscuro makes the film’s epic scope and scale appear more monolithic, and as a result, more intimidating, complementing the film’s admittedly unwieldy appearance as far as the material is concerned. The ambiguity of its ending contains its own heaviness, philosophically speaking, and feels a more proper resolution for film noir, as well.

7. Laura (1944)

It’s oft been spoken about, but a cynical view is a requirement for film noir, though it isn’t the only one, of course. For Otto Preminger’s Laura, however, it isn’t explicitly so – at least, not as much as some of its contemporaries. The pessimism certainly develops as the plot progresses, finishing with a gloomy ending, as many of its kind do. Its opening act is a curious one, as the characters are thrust into the midst of the investigation without the audience having any knowledge of the crime committed.

Additionally, the tone feels like that of a eulogy, which is plausible considering much of the narrative in this portion is told through flashbacks. This sort of atmosphere seems somewhat antithetical to the genre’s conventions, but by Laura’s conclusion, it morphs into something more appropriately familiar. Rounded out by strong performances from its cast, Laura stands out as one of the leading classics of the genre.

6. Memento (2000)

In Christopher Nolan’s Memento, the moral ambiguity previously discussed with Insomnia flourishes in spades, and it's what first brought the director into the limelight. Furthermore, our protagonist’s (Guy Pearce's Leonard Shelby), anterograde amnesia makes this theme all the more troubling. But as worrying as his condition is, his being an unreliable protagonist and narrator, of sorts, makes his journey that much more captivating.

Further aided by Nolan’s unique narrative structure of reversing the present and playing the past chronologically, the audience is given a distinctive view of a man’s psychological condition. And though the film’s emotionally charged opening may exonerate him of any innocence, we still remain hooked because we realize the real mystery isn’t who raped and murdered his wife, but rather how he got to the film’s "finale." It’s a peculiar neo-noir that carefully unwraps its deep-seated cynicism over the course of a shifting narrative rather than explicitly showing it through visuals and/or characterization.

For inquiring minds, the 2 disc Collector's Edition for Memento features an option for the viewer to watch the movie in reverse.

5. The Big Lebowski (1998)

It’s a neo-noir post-western black comedy detective story, and it’s completely mental – or at least the Coen brothers were. Since its release in 1998, The Big Lebowski has entertained college students and the drug-impaired alike, often time killing those two birds with one stone. Those genre specifics mentioned previously are mostly overlooked when encountering the feature, but considering how well the players engage with the Coen brothers’ material, one can be forgiven for just watching for a handful of moments’ sake.

A lot of personalities associated with films on this list are affable by way of their various forms of coolness, the sorts of cool that fall in line with traditional depictions of masculinity. It may just be a hunch, but the Dude (Jeff Bridges) isn’t the type to be very concerned with how he presents himself. He’s just the Dude, and that’s about as complicated as he needs to be. However, the Coens pleasantly oblige in throwing him in the midst of a gleefully baffling tale of absurdist fiction.

4. Vertigo (1958)

Alfred Hitchcock has a bevy of famous films attached to his name, but Vertigo is arguably one of his greatest. The film starts out of with an impactful bang as Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart) watches as a fellow police officer falls to his death trying to save him from hanging on a ledge, and though the film becomes more psychological from this moment forward, it never loses its punch. With Hitchcock’s penchant for unexpected twists and deceitful characters, the narrative remains as tight as any of his shot compositions.

Hitchcock’s film is an example of the mystery or investigation playing secondary to the relationships built between two characters, and what’s equally as fascinating as the narrative Hitchcock spins are the theories regarding its themes. Many have posited that, implicitly, or perhaps explicitly, Vertigo speaks to male control of visuals as it relates to femininity and masculinity, and thereby questioning the dominant male perceptions of both. In that case, Vertigo is a progressive film for its time.

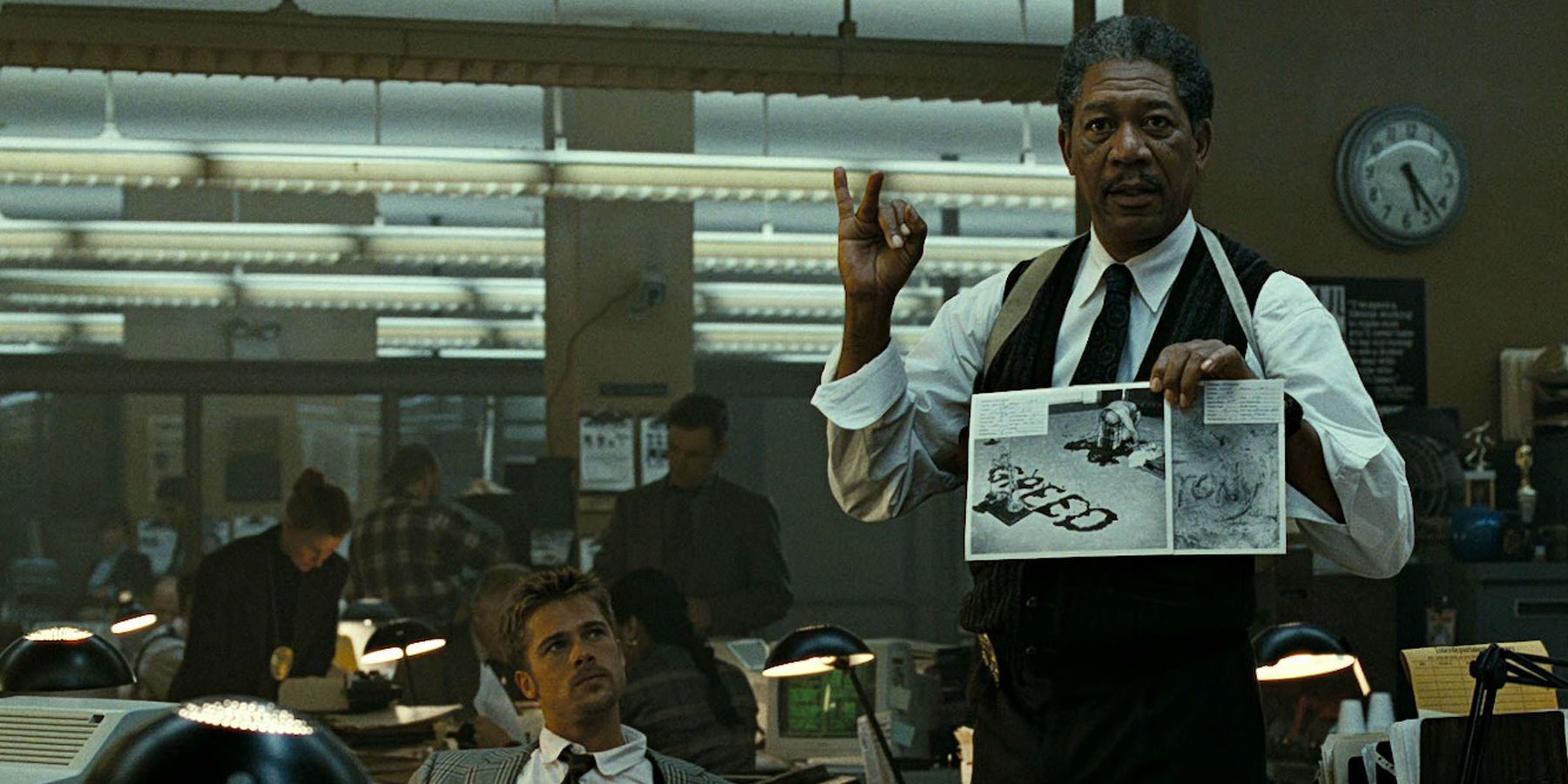

3. Seven (1995)

David Fincher is one of those directors whose work is anxiously anticipated and endlessly hyped, and after the infamous Alien 3, he truly announced his presence in the industry with Seven, a notorious murder mystery about victims killed based upon the Seven Deadly Sins. There’s a lot about Fincher’s film to be celebrated; for example, his gritty, uncompromising view of the crimes and a brilliantly disturbing use of the idea that what’s scariest is not what you see, but what you imagine. Not to mention a heavy-hitting ending drained of any ounce of hope.

Praise is often sent in the direction of its two leads, Morgan Freeman and Brad Pitt, on an individual basis, but perhaps not as much is said about their onscreen partnership. Through a convincing, purposeful lack of chemistry between the two as characters, one can easily identify the chemistry between the two as actors. Though we follow and latch onto Detective Somerset (Freeman) for his studious and quietly authoritative mannerisms, the somewhat psychological exploration of Mills (Pitt) becomes its own side narrative, providing much of the impact the ending has.

2. The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs is a rather unique case here. On the one hand, it is a bona fide detective story as FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) hunts down a deranged serial killer known as Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine). On the other, this film is equally about Starling’s relationship with Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) and the numerous psychological games of dominance he plays with her as he cooperates with her case. In many ways, Starling’s pursuit of Buffalo Bill feels secondary, much like James Stewart's mystery in Vertigo.

And yet, the screenplay remains absolutely focused, even as much time is given to Hannibal’s escape from confinement. The investigation itself may feel secondary to everything else, but we are still treated to Bill and all of his disturbing madness, including some oddly quotable lines (don't worry, Lecter has his fair share, too). Additionally, we are equally caught up in the chase because of its two conflicting personalities; compared to Levine’s loose cannon Buffalo Bill, Hopkins’s Lecter is more refined, if sometimes improvised.

1. The Maltese Falcon (1941)

No list about detective films would be complete without at least one Humphrey Bogart entry, and what better film to proclaim his greatness than The Maltese Falcon? One could argue Casablanca is his greatest film, this writer included, but along with the classic High Sierra, The Maltese Falcon is where he truly announced his arrival as Hollywood’s next big star. Every stereotypical hard-boiled film noir gumshoe has been modeled after performances like his, especially his playing Sam Spade from Dashiell Hammett’s novel of the same name.

But of course, the movie is more than just Bogie; Mary Astor and Peter Lorre provide their own phenomenal turns, as well. It’s every lowly lit room to heighten the tension and every dramatic angle of characters sitting and conversing to play with the audience’s perception of power. No one copies and pastes aesthetics if the reason weren’t their greatness, and The Maltese Falcon is a pretty fine blueprint.

---

Were there any absentee mysteries that should've made the list? Let us know in the comments!